Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) cast a very long shadow over the 20th century, not least in England. Although he did not visit this country often, he apparently had a high regard for it, despite his somewhat sketchy knowledge of its contemporary painters. He once complained, ‘Why, when I ask about modern artists in England, am I always told about Duncan Grant?’ This remark is usually taken as a slight to Grant, though the two knew each other and maintained friendly relations. In Tate Britain’s exhibition Picasso and Modern British Art (until 15 July) Grant is triumphantly vindicated — one of the show’s pleasant surprises — and we are reminded that he was indeed an artist of considerable stature before he subsided into the late long years of whimsical decoration.

Grant is one of the featured English artists along with Wyndham Lewis, Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, Graham Sutherland and David Hockney. Each of the British contingent is allotted a room, while Picasso’s work is hung among and between them, like a thread through the maze or a touchpaper leading to explosions of various magnitudes. It’s a large exhibition of over 150 works, of which more than a third are by Picasso, yet it doesn’t feel too big. The organisers have tried to gather works by Picasso that were once (or still are) in British collections, and so might have been familiar to our artists, though I suspect that more were known through reproductions in the leading French art magazines. But however his influence was disseminated, it was soon recognised in all quarters.

The exhibition opens with examples of Picasso’s early work (Blue and Rose periods and a couple of Cubist things) and then moves on to Duncan Grant and Wyndham Lewis, who doesn’t fare particularly well, though there’s a lovely watercolour drawing, ‘Archimedes Reconnoitring the Fleet’, 1922. The Grants, especially ‘The Tub’, c.1913, ‘The Modelling Stand’ (c.1914) and ‘The White Jug’ (1914–18), are more impressive — a comparative judgment I never expected to make. There’s a whole mass of Picasso drawings and costume designs for the ballet The Three-Cornered Hat, but the most interesting thing in this section is a previously unexhibited portrait drawing of Vladimir Polunin, the Ballets Russes’ principal scene painter and stage-design tutor at the Slade. (He taught Mary Fedden, among many others.)

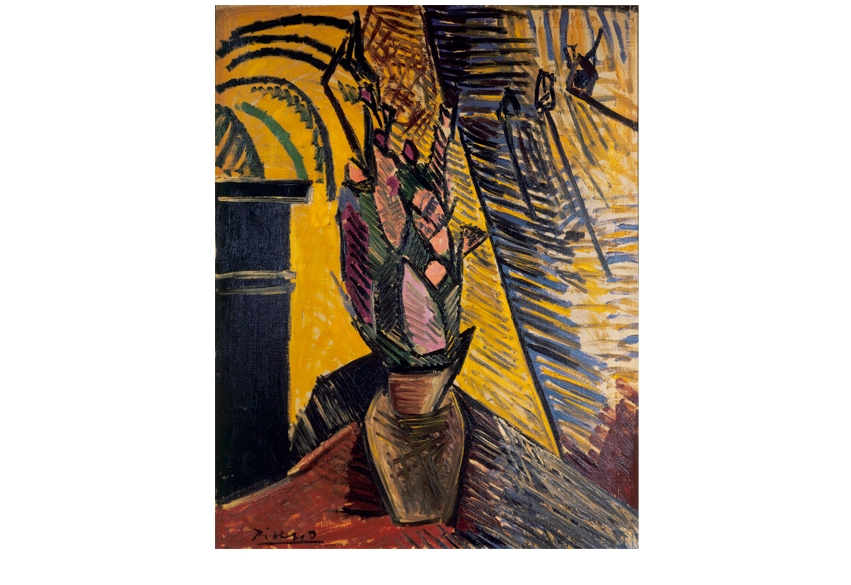

In the Ben Nicholson and Picasso room there are lovely things, such as Picasso’s ‘Guitar, Compote Dish and Grapes’ (1924) next to Nicholson’s ‘1932 (Au Chat Botté)’, with ‘1932 (crowned head — the queen)’ at right angles. But there are a couple of musical instrument paintings by Nicholson that weaken the argument — best to move on to the big room of Picasso’s work. From the vibrant and brushy ‘Blue Roofs, Paris’ (1901) to the angularity of ‘Bust of a Woman’ (1909) to the tougher Cubism of ‘Man with a Clarinet’ (1911–12) and the more decorative ‘Still-life with Garlands’ (1918), then on to the marvellously sexy ‘Nude Woman in a Red Armchair’ (1932) and thence to the collages and constructions — this is a fabulous rollercoaster of a room. Henry Moore comes next: a superb selection of less familiar work with one of the finest Picassos of the show: ‘Standing Nude’ (1928). There are good things in the Bacon room, though rather too much early work, and the same goes for Sutherland. Hockney looks better, perhaps because he stays so close to Picasso. The show ends with a bang: the great Picasso of 1925, ‘The Three Dancers’, which he admitted meant more to him as an artist than even ‘Guernica’.

Although full of interest, this exhibition plumps too thoroughly for the obvious suspects, and in the process misses out much else. Picasso’s influence, for many an overpowering if not malign shade, was felt by a whole generation of artists, of varying degrees of interest and competence, none of whom gets a look in. I think the organisers missed a trick here, and if, instead of including quite so many unimpressive paintings by Nicholson, Bacon and Sutherland, they had devoted a room to the lesser-known Picasso-affected, the exhibition would have been both stronger and more representative.

Among the artists that suggest themselves are John Craxton, the two Roberts, Colquhoun and MacBryde, Jankel Adler (their direct link to Paris), Eileen Agar, who knew Picasso through Roland Penrose, and whose 1930s works make a very interesting comparison with, in particular, Picasso’s ‘Head of a Woman’ drawing from 1926, and, lastly, Michael Ayrton. In some respects, Ayrton’s career was blighted by Picasso, for he had the temerity to question and attack the master in print, while sharing many of the same classical preoccupations. Some never forgave Ayrton for his adverse criticism (Craxton among them), and the fact that Ayrton’s line-work often looked a bit

Picasso-esque didn’t help.

Although all these artists are mentioned in the catalogue, to have exhibited examples of their work would have enlarged our perception of the varied response that Picasso’s work aroused. If you miss it in London, the exhibition is touring to the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh (4 August to 4 November). It’s certainly worth seeing: there are some great pictures and sculptures, and it’s a pleasure to report that by no means all of them are by Picasso.

A contrasting exhibition of British sculpture from the 1950s and 60s (at Pangolin London, King’s Place, 90 York Way, N1, until 3 March) offers an alternative take on the Picasso effect, mingled with other influences such as Calder and Giacometti. Here are sculptors of a younger generation than Moore, in turn inspired by Picasso (and Moore) or reacting against his presence: principally, Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick, Geoffrey Clarke, Elisabeth Frink, George Fullard, Eduardo Paolozzi and William Turnbull.

Despite the spikiness of the so-called ‘Geometry of Fear’ of this angst-ridden crew, there are some very enjoyable works on show, ranging from a couple of Robert Adams carvings to a series of Geoffrey Clarke’s potent etchings, via the under-appreciated George Fullard, represented here by a drawing and a couple of bronzes. There’s even a Sentinel figure by Michael Ayrton. A great puffed-up frog by Paolozzi looks as if it were about to explode, while a ‘Bullfrog’ by Chadwick has a revolving razor-sharp toothed jaw that could take chunks out of you. Visit the show and exorcise the fear…

Comments