In 1951, Winston Churchill, then leader of the opposition and aged 77, scored a humiliating Commons victory over the new chancellor of the exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell. Not for nothing did Aneurin Bevan call Gaitskell ‘a desiccated calculating machine’. His dry Wykehamist tone made his financial statements seem interminable, and this one soon had the House restless. Churchill made a diversion. He began to search his pockets. First the two side-pockets of his trousers. Then the two at the back. The top jacket pocket followed. The House gradually lost interest in Gaitskell and followed Churchill’s investigations as he moved to the inner and the side-pockets of his coat and then his six waistcoat pockets. Exasperated beyond endurance, Gaitskell threw down his brief and asked acidly, ‘Can I be of any assistance?’ Innocently surprised, the old man looked up and said, ‘I was only looking for a jujube.’ The House dissolved in laughter, and Gaitskell was lost.

Now the point of the story is that if Churchill had been a woman, he could not have staged this performance. For women have no pockets. Why? The question takes us into the murkier depths of the sex war as well as the arcana of sartorial history. In the 19th century the skills of the Savile Row tailors devised a male suit that has remained standard for over 100 years, giving its owner 17 pockets in which to distribute all his keys, watch, notecase, money, matches, hanky etc without seriously altering his shape. If he had a good figure — wide shoulders, narrow hip — the suit preserved it while keeping all his knick-knacks within reach. It is typical of the perception of Thomas Carlyle (whose own rustic suitings were concealed beneath an elongated overcoat) that he noted the centrality of the suit, and especially of trousers, in his 1838 tract Sartor Resartus. To him, trousers and advanced culture — especially male culture — were inseparable. Trousers made possible pockets, to Carlyle a ‘marvellous natural invention’, part of the way civilisation ‘armed the body for the market-place’.

In fact trousers, let alone pockets in them, had primitive origins. They were the mark of the French peasants and workmen, the sans-culottes, who did not wear elaborate breeches or culottes, of fine wool, silk or satin, but what were later called dungarees or overalls. In the early 1790s, members of the Assemblée nationale adopted them. The fashion spread across the Channel when the advanced Whigs, led by Charles James Fox, adopted trousers. At this point the tailor stepped in, turning the rustic garment into elegant attire by making it of superfine cloth, shaping it to the leg, adding pockets, and putting an elastic band under the instep — a device which delighted smart cavalry regiments and, according to George Orwell in 1947, ‘gave you a feeling like nothing else on earth’. Beau Brummell was both architect and beneficiary of the ‘smart trousers’, which made male legs so alluring in ladies’ eyes that Pope Pius VII condemned them as sinful, and the garment was taboo in Rome until 1827. But everywhere else it flourished mightily.

If the tricoteuse had adopted trousers at the same time as the male sans-culottes, the history of the world might have been different. But the French revolution did nothing for women. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, kissed Westminster electors on behalf of Fox wearing voluminous and inconvenient skirts. Women did not even have the help of sensible underclothes. They wore petticoats, up to a dozen at a time. What were then called drawers, later knickers, were denied to all except prostitutes and dancers, who needed to show their legs. Drawers for respectable women did not begin to come in until about the time the papacy dropped its opposition to trousers.

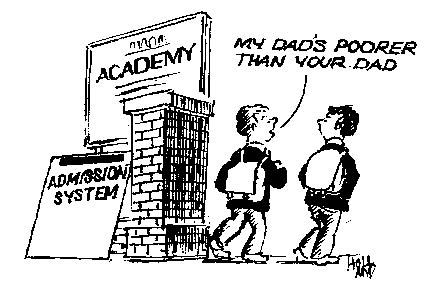

If women were denied trousers, why could not they be given pockets? This question is discussed in an ingenious article in a recent issue of Victorian Studies. In ‘Form and Deformity: the Trouble with Victorian Pockets’, the American scholar C.T. Matthews discusses 19th-century writers who analysed fashions with a view to drawing social lessons. The record shows that the absence of pockets was a huge disadvantage to females and one reason why male superiority was so steadfastly maintained. James Robinson Planché’s Cyclopaedia of Costume (1879) called the adoption of trousers a sign of cultural triumph of ‘North over South, Protestant over Catholic, Angle over Celt’, and indeed, men over women. Six years later Isaac Walker, in Dress: As it Has Been, Is and Will Be, called ‘cylindrical clothes’ the ‘costume of civilised man’.

Women might have been given internal pockets but were denied them, too. It was argued that they had four external bulges already — two breasts and two hips — and a money pocket inside their dress would make an ungainly fifth. Instead there developed two external devices. One was the chatelaine or belt, an updating of the medieval girdle, on which keys and purses hung on hooks. This was awkward, and lent itself to ridicule in papers like Punch. The coming of the crinoline made it impossible to wear and by the time that had gone out of fashion the chatelaine had been abolished too. Instead there was the handbag, which evolved in the late 19th century out of the traditional workbag, in which ladies kept their sewing and knitting. The point about the handbag was that it was and is external to the body, and has to be carried. This increases female dependence and limits freedom of action. Moreover, whereas pockets are distributed about the person with a view to differentiated purposes, so that a man knows where everything is and can find it instantly, a bag is exactly that, a thing into which every needful article is indiscriminately thrown, so that much time is wasted in searching, quite apart from the risk of mislaying the bag itself. I heard of a case of an English society lady visiting New York who went for a coffee, and foolishly placed her bag on the floor near her chair. It was stealthily whipped, and she found herself in a strange and hard city without money, keys, travellers’ cheques, ticket, passport and Filofax, indeed all the necessities of life. This predicament could never have enveloped a man.

The 20th century brought women, in theory, trousers and pockets. But a clothes industry run by men, and a fashion trade dominated by homosexuals, ensured this made little difference. Tight jeans will not accommodate useful pockets. I remember Christian Dior saying to me in 1954: ‘Men have pockets to keep things in, women for decoration.’ Handbags have become much more important in women’s appearance and practical life than they were in the 19th century, and relatively more expensive. Bigger, too. And in my observation, women spend a much greater proportion of their lives looking for mislaid objects than men do. It is true that women of genius overcome their disabilities. Margaret Thatcher made superb aggressive use of her handbag, for instance. I can still hear the sound of it snapping triumphantly. But few have her skills. Most are left, literally, out of pocket.

Comments