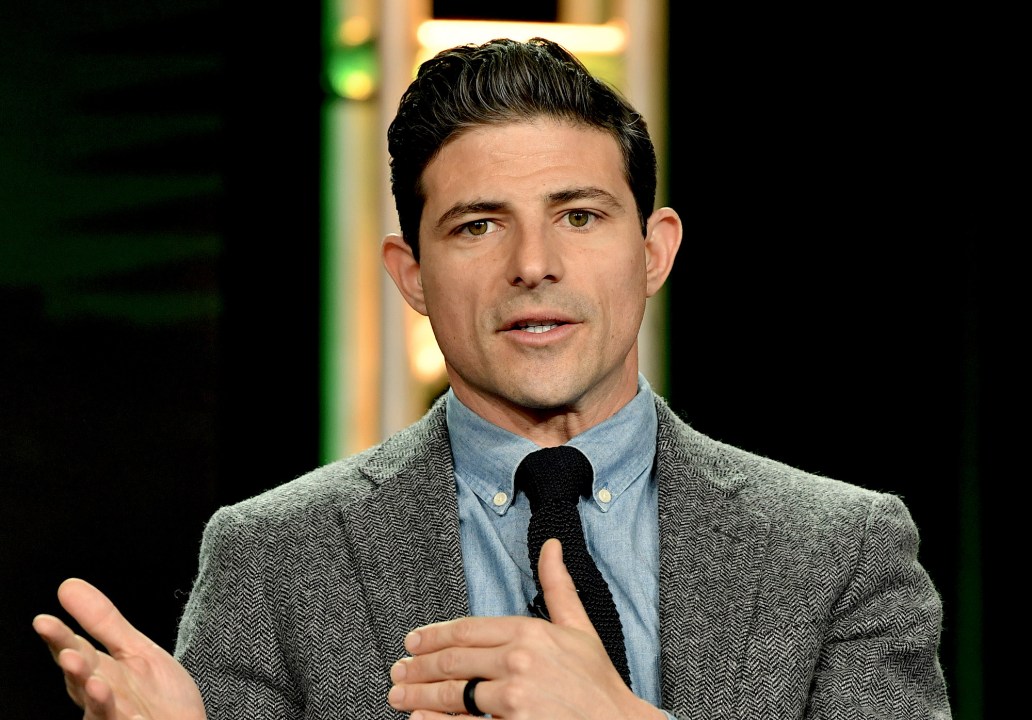

Matt Gutman has the hairstyle of Anderson Cooper and the literary style of Danielle Steel.

In a special report on the Charlie Kirk assassination, ABC News’s chief national correspondent wistfully described text messages between the suspect, Tyler Robinson, and his roommate and alleged boyfriend. The exchanges were, Gutman gushed, ‘very touching in a way that I think many of us didn’t expect’ and ‘a very intimate portrait into this relationship’. Gutman quoted Robinson’s sweet nothings (‘my love’ and ‘I want to protect you, my love’) and mused on a ‘duality’ between the aggravated murder charge and ‘on the other hand, he was, you know, speaking so lovingly about his partner’.

Gutman wasn’t done, and the longer he spoke, the purpler the prose became. Robinson’s messages were ‘so fulsome, so robust, so apparently, allegedly self-incriminating and yet, on the hand, so touching’. Returning to Robinson’s reported intentions towards his roommate, Gutman reminded us that ‘he was trying to protect him’. Thus there was ‘this heartbreaking duality that we’re seeing very tragically playing out here’.

Most network correspondents dream of winning a Polk or a Peabody. Gutman is going for a Romance Writers of America award.

Two points before we go any further. One: Robinson is innocent until proved guilty. Two: Reporting live on camera under pressure is a feat and neither experience nor ability a safeguard against poor word choice, so Gutman deserves some slack. Even so, it is bracing to hear a leading journalist speak about a murder suspect in such terms. Shading in the initial sketch of the accused is part of the job, getting misty-eyed about his dedication to his reported boyfriend is very much not.

Might I hazard a guess at what is going on here? After initial efforts to frame Kirk’s murder as the action of a far-right 4chan edgelord, mainstream media journalists now must contend with the grave possibility that the conservative activist’s alleged killer grew up in a Republican family, was radicalised to the left at college, where he met and seemingly fell in love with his trans roommate, then gunned down a critic of leftism and gender ideology. I don’t know whether this is any closer to the truth than the groyper-gunman theory, but it is a much more difficult frame for network reporters to process. After years of neglecting, downplaying and even excusing leftist violence, all the while echoing progressive hysteria about even the most mainstream Republicans, the mainstream media now must explain how Charlie Kirk became the only recorded victim of Trump’s trans genocide.

Yet the trans angle is also the most fruitful for journalists and progressives. If the story becomes one of tragic love and desperation and the fears of an oppressed minority, no one will be talking about politics anymore. Is political violence in the United States really the preserve of the right, or does the left have a problem with it, too? Did allowing activism and catastrophism too large a role in news reporting and analysis create an atmosphere of existential alarm among some already troubled people? In characterising political speech to the right of David French as fascism, racism, transphobia, and the rest, did Democrats and mainstream reporters place a target on conservative public figures like Kirk?

If this is the thought process, it says nothing good about the condition of American civic life. It says there are Americans who can more readily empathise with an alleged murderer because of his minority status than with the married father of two he allegedly murdered. I would say this is the inevitable end point of progressive identity politics but I suspect the road to hell has more stopovers yet to go.

What might cause a person to respond this way? Fanatical partisanship? Perhaps. Suicidal empathy? The right would certainly say so. My ‘law of displaced culpability’ (the more acutely an event exposes the shortcomings of liberalism, the more zealously elite institutions will strive to reassign blame)? Could be. Or perhaps it is a rejection of moral responsibility, of the very notion that there is right and wrong and those who freely do wrong should account for it.

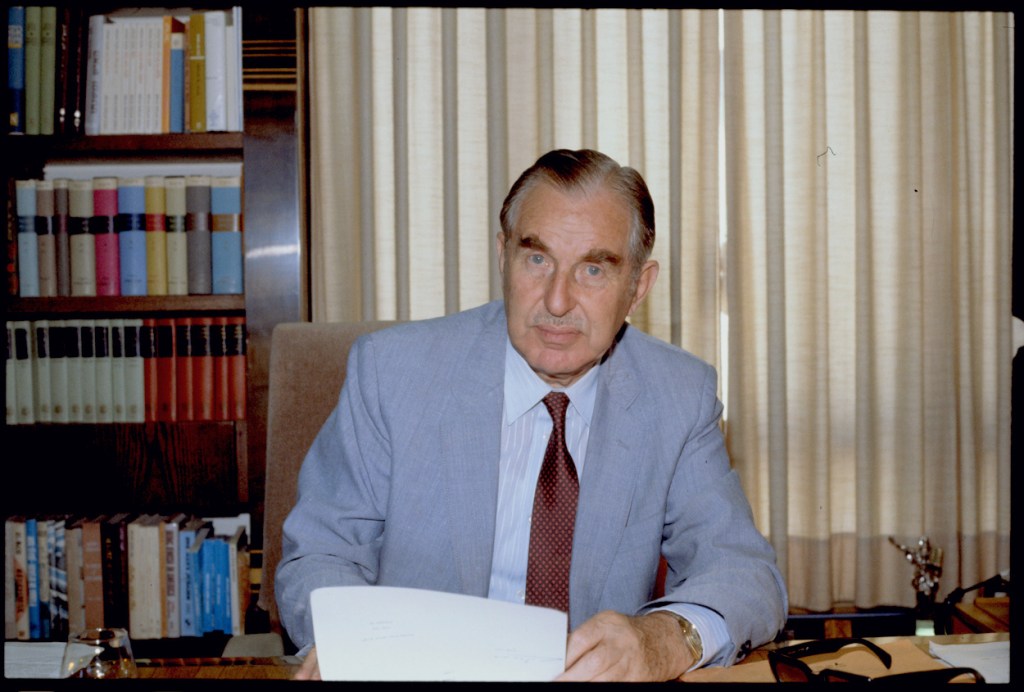

There is a famous precedent here. When John Hinckley Jr, Ronald Reagan’s would-be assassin, was found not guilty by reason of insanity at his 1982 trial, the fiercest and most eloquent protest came not from the right but from Dan Rather, paladin of crusading liberal journalism, on his CBS Radio broadcast. Hinckley had wounded not only the president but Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy, police officer Thomas Delahanty, and White House press secretary James Brady, who was paralysed and died from his injuries three decades later.

The attack was planned and motivated, it was said, by the gunman’s desire to impress Jodie Foster, having become fixated on her performance in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976). Hinckley acquired the slickest of trial attorneys – his father was an energy tycoon – and a succession of defence psychiatrists assured the court that Hinckley was unable to distinguish between the movie and real life and was therefore legally insane. The jury bought it.

The next day Rather got behind his microphone, from which had come so much to consternate conservatives, and offered a verse that rhymed with the thoughts of many Americans. ‘The insane are among us, it is true,’ he said. ‘But so are the calculating.’ It was well-known that money talked, but ‘in the Hinckley case money yelled and banged on the table and won the day’. The poor, whites and blacks alike, went to prison for ‘the usual assortment of human transgressions’ but this lost little rich boy could shoot the president, establish a disorder, and become a tormented victim, absolved of legal culpability.

Rather’s ire was not directed only to social injustice but to moral decadence. The verdict sent the message that ‘the more heinous the crime the crazier you must be’ and thus ‘you are not responsible, and nothing is your fault. ‘Something is wrong here,’ he concluded. ‘Wrong about this age of millionaire assassins and high-powered lawyers and cool talk about the secrets of the mind — and no talk about old abstractions like responsibility and punishment and sin.’

It’s hard to imagine a liberal talking like this today, not even and perhaps especially not of Charlie Kirk’s alleged assassin. Moral judgement is determined by identity, not behaviour, and victim status cannot be revoked – provided any harm done is done against those with victimiser status. The accused is gay and supposedly dating a trans-identifying guy. Kirk was a white, reactionary, Christian, Zionist, gender-disbeliever. The moral die was cast long before ballistics had their say.

In his short story The Generous Gambler, Charles Pierre Baudelaire has the Devil offer the narrator, as a consolation for the loss of his soul, ‘the possibility of solacing and of conquering, during your whole life, this bizarre affection of ennui, which is the source of all your maladies and of all your miseries’. Aversion to the mundane, to the ennui of the ordered life, can leave us longing for transgression and its alluring excitements. Kirk espoused the ordered life. Those who cannot find solace in that life hope to conquer it by romanticising destruction physical and moral. Worship of disorder is worship of the generous gambler.

Comments