In a very specific and limited way, I have concerns about the Internal Market bill. It’s not a bad bill; on the whole, it is a welcome piece of legislation that attempts to bring some cogency to regulation and practice as we exit the EU. The bill will make it easier to trade and contract with and within the UK, standardising and simplifying a regulatory terrain that currently resembles the obstacle course at Sandhurst. It also establishes in black and white UK ministers’ power to invest directly in devolved nations, including via transfers to local authorities.

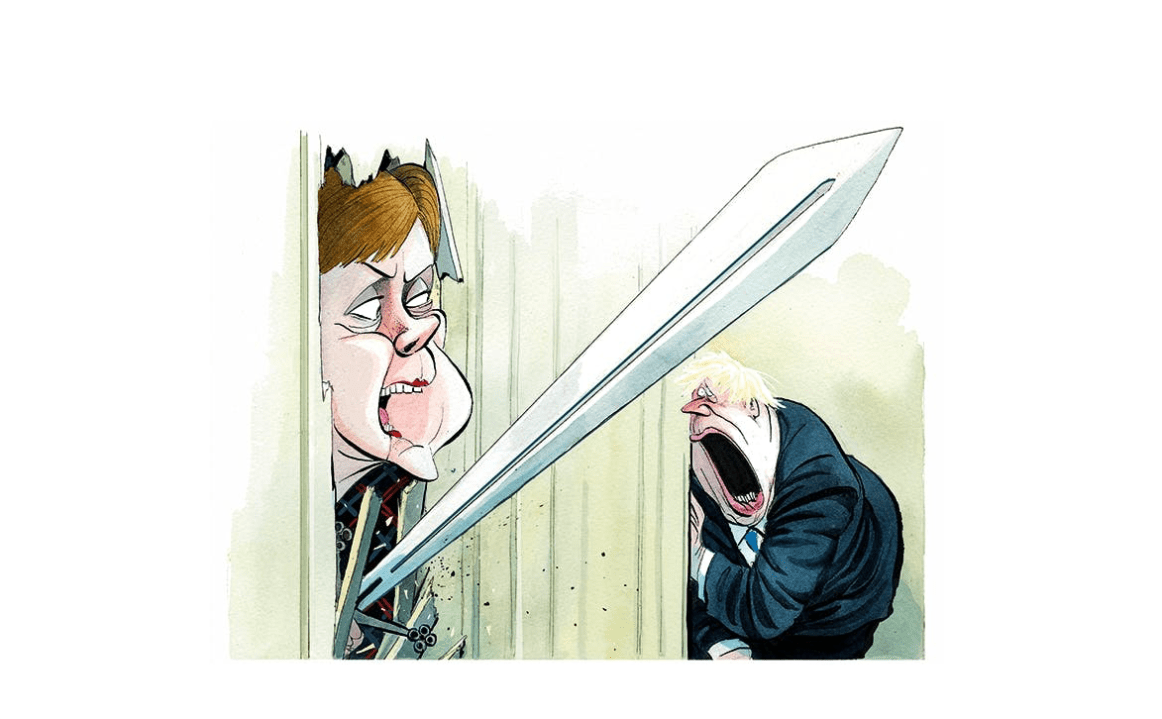

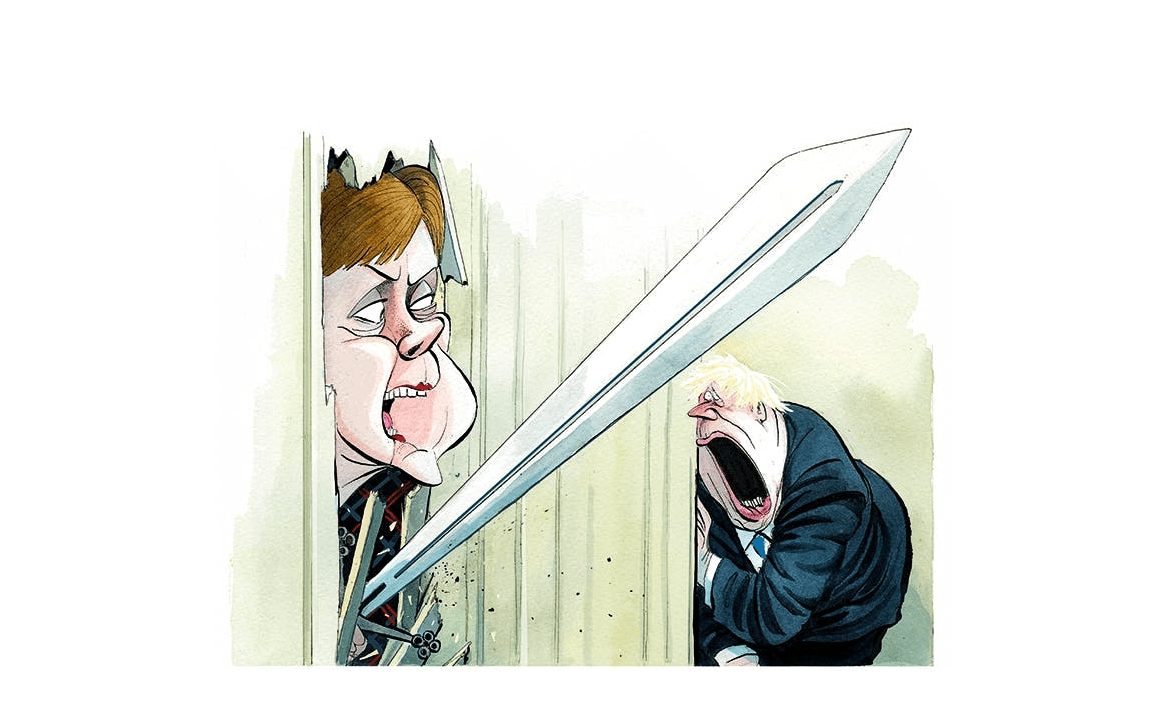

Since the first hint of the bill’s contents, the SNP has been squalling that the UK government is mounting a ‘power grab’ to undermine their bailiwick of belligerence at Holyrood. (If only the actual UK government was half as enterprising as the one that stalks the imagination of the SNP.) Now that the direct funding mechanism is public knowledge, the separatists and some devocrats are splenetic at the thought of the United Kingdom government governing the United Kingdom. Devolution, in its theory and in its structures, established a proto-state, one which the SNP aims to drive right out the front door. The Internal Market bill amounts to little more than a boom barrier but it’s still too much for the nationalists and their devocrat sidekicks.

It has become infinitely easier for Nicola Sturgeon to rail against this piece of legislation

Where my concern lies is in the jiggery-pokery being attempted on the Withdrawal Agreement. Everyone breaks international law because, as it is practised by governments and international organisations, international law is politics by another means. As one Tory remarked to me: ‘What they are proposing to do is pretty outrageous. It’s like something the French would do.’

The difference here is that the government has admitted up front – from the dispatch box of the Treasury benches, no less ≠ that it intends to break international law. This will be no mistake, no legislative boo-boo caused by poor drafting or shonky legal advice. Ministers are going out of their way to contravene a treaty. That sends a message not only to countries and international bodies that might do business with us in the future – it also telegraphs contempt for a rules-based order that the UK has helped fashion and enforce and which we have prayed in aid when others have acted with disregard for established rules and norms.

I doubt the general public – or, more specifically, the 40 per cent or so the Tories must hold onto – will be terribly exercised by all this. Brexiteers want Brexit done by whatever means necessary. For Tories more generally, resignations from civil servants and indignation from the legal profession will only convince them that the government is on the right path. The Tories used to be the party of the establishment and few were more establishment than civil servants and barristers. Nowadays such people belong to the new establishment – vaguely Labour but defiantly Remain, culturally progressive and placing more confidence in courts and global bodies than in parliament or democracy. The rule of law Conservatives once put their total faith in has been displaced, in their minds, by the rule of lawyers – activist lawyers.

That particular evolution of British conservatism I’ll leave alone for now, because the more pressing fact is the impact of the government’s self-confessed law-breaking on the SNP’s case against the bill. In short, it has become infinitely easier for Nicola Sturgeon to rail against a piece of legislation mired in controversy about an international treaty than it would have been had the bill stuck to regulatory matters. Before, she would have had to convince Scots that a bill that simplified trade, made life more straightforward for businesses, and could bring more money from the Treasury was a bad deal for Scotland. Now she can slip in her partisan, nationalist objections under the guise of concern for international law. Ministers have done the SNP a real solid here.

What I struggle to understand is why ministers are prepared to be pelted with brickbats for what is a politically modest piece of legislation. It is not just the UK’s single market that is a mess but its constitution and, given rising support for Scexit and Cymrexit, this would be an opportune time to pass legislative reform of devolution to strengthen the Union. The same brickbats would come flying but at least now the pain would be worth it.

Comments