One fine day in June 1896, a lone Russian nihilist visited Leo Tolstoy on his country estate. Come to hear the master, the stranger questioned Tolstoy about his latest beliefs. Satisfied, he left later that day. But then he returned with a written confession. He was an undercover policeman, sent to check on what Tolstoy was up to. Deeply ashamed of his deception, he begged for forgiveness.

This vignette, recounted by Alexandra Popoff in her new book about Tolstoy’s later life, perfectly captures the author’s power. Whether through his fiction or radical Christianity, Tolstoy could fascinate and compel in equal measure. Though the government spy was dismissed for his bungling, it is hard to imagine his regret at being seen as himself by the literary master turned prophet.

In Tolstoy’s False Disciple, Popoff portrays Tolstoy’s most famous follower: Vladimir Chertkov. Popoff gained access to Chertkov’s archives, closed because considered incomplete, in the Russian State Library (though, strangely, she does not say how she bypassed the typically intransigent Russian bureaucracy). The result is a well-written, polemical view of Tolstoy’s self-appointed vicar on earth.

So who was Chertkov? Wealthy and well-connected, he began his career in the Russian Horse Guards. Proud to be considered Tsar Alexander II’s illegitimate son, he attended the best parties, spoke fluent French (Tolstoy would later be frustrated by his sometimes patchy Russian) and knew everyone who mattered.

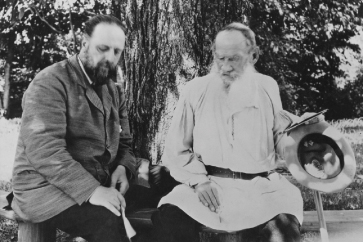

Within a few years, however, he felt unsatisfied. He began to consider life as a landlord or Justice of the Peace. Then, meeting Tolstoy through mutual friends in 1883, he was delighted by the latter’s moral seriousness. The two became close and Chert-kov began a decades-long process of editing, translating and publishing Tolstoy. He did not restrict himself to religion, asking for Tolstoy’s diaries (which he got), occasional notes (also supplied) and new fiction (more closely guarded).

The view of Chertkov as a parasitic hypocrite can be traced back to Sophia, Tolstoy’s long-suffering wife. Not unfairly jealous, she noted Chertkov’s continued aristocratic habits, clashing with his supposed asceticism, and his discourtesies to her and the couple’s children.

Following Sophia’s lead, Popoff has nothing positive to say about Chertkov. We see him bullying Tolstoy, feuding with associates and shamelessly presenting himself as more Tolstoyan than Tolstoy. In one memorable passage, Popoff berates Chertkov for getting Tolstoy to buy him a box of asparagus, only to send him back like a servant on discovering they were wilted.

Popoff’s Tolstoy, aware of Chertkov’s limitations (if he had not found religion, he is said to have remarked, he would have become a governor general and hanged people), is paralysed by his Christian self-abnegation and pleasure at having a disciple. The possibility of a genuinely rewarding relationship is not entertained.

Popoff’s new research uncovers Chert-kov’s links to the secret police. The allegation is that he stored Tolstoy’s diaries at an ultra-conservative’s address, giving the government the opportunity to check on Tolstoy without a need for cloak and daggers. This points to an unscrupulous, perhaps genuinely villainous side to Chertkov, but the killer punch — the exposure of him as a paid-up police agent, for example — never comes.

In the end, the most interesting relationship of Tolstoy’s later life has always been between his later and earlier selves. The vehemence with which the thinker rejected the novelist mystified many at the time and since. Popoff’s new book attacking his foremost follower cannot help but feel like a displaced disagreement with Tolstoy, one which avoids meeting him on his own terms. That untold story might make for a more honest, if potentially discomforting endeavour: one sure to find a curious audience.

Comments