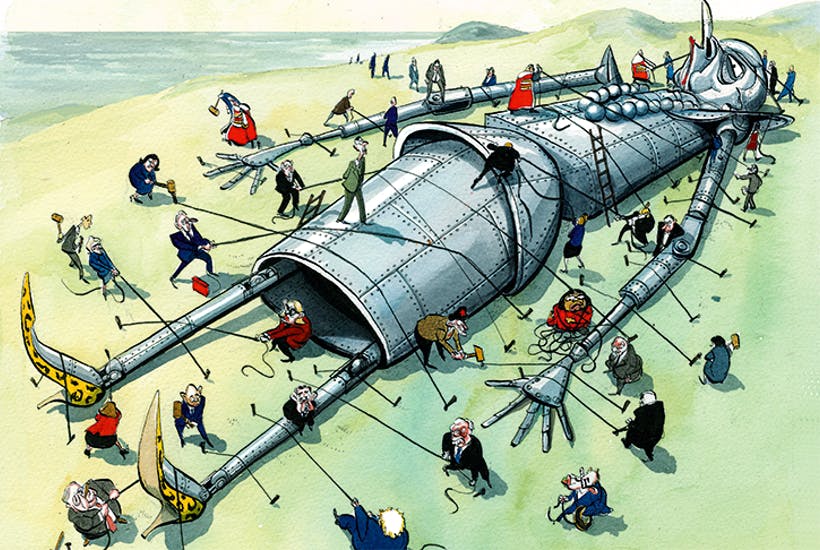

Brexit is an accident born of misunderstanding. One of the biggest miscalculations is about the EU and how it works. Troublingly, that misjudgement, embraced by both unwise Leavers and imprudent Remainers, could just lead Britain off a cliff, for the second time in three years.

I attended my first EU summit in 2001 and stopped counting the number of Council meetings, ECOFINs and other EU gatherings when the figure passed 50 some time early in the financial crisis. I’ve seen a lot of British politicians go to Brussels (and elsewhere, in those innocent days before the Belgians captured all council meetings for their capital) and pursue the British national interest, with varying degrees of success. One notion that came up time and time again in such dealings is this: if the EU could just understand the depth of British concern about a particular European issue, the other leaders at the council table would realise that they need to give more ground and go further to accommodate British wishes.

The most frequent exponents of this theory have been Conservative eurosceptics. Time and again, they’d howl with fury about British policy in Europe, explaining that if only [insert Prime Minister’s name here] had shown some real steel and told the EU that people in the UK (or at least in Parliament) were hopping mad and that unless they give Britain what it wanted, well, those people would get even angrier.

Indeed, under David Cameron it was sometimes argued by Tory sceptics that parliamentary rebellions over various bits of EU business were actually helpful to the PM, since they allowed him to go to Brussels and say, in terms, “you’ve got to help me out here because if you don’t my party will lynch me”.

That theory overlooks several inconvenient facts about the EU and the heads of other EU member states, the most important of which is this: that’s not how the EU works, how it’s ever worked or how it was ever meant to work. The project is about rejecting that sort of populism and demonstrating that nations prosper when they adhere to shared goals. And besides, all the other leaders at the table have domestic politics to consider too: why would they risk upsetting their own voters to help a British PM keep British voters quiet?

None of this is complicated or secret, yet the idea that if Britain just pushes hard enough, the EU will fold persists, impervious to all evidence. Last week, one senior Tory leaver told me, with a straight face, that “EU negotiation is about brinkmanship but our problem is we’ve never taken it to the brink.”

In fact, we decided in June 2016 to jump headlong over that brink. And we did so because the EU didn’t blink. David Cameron’s entire attempt to renegotiate the British membership was an attempt to validate that sceptic theory that if we just cut up rough enough, the Europeans will back down and give us what we want. And remember how that worked out. Yes, EU leaders did their best to be polite to Cameron and help him out – they didn’t, after all, want him to lose the referendum. But they wouldn’t pay any price to accommodate Britain. EU unity and the integrity of the Four Freedoms matter more.

You can argue that if the EU had listened to all those earlier warnings about British anger, the whole accident of Brexit could have been averted. But that’s an academic point: the EU is what is it, and that is an entity that has demonstrated, consistently and over many years, that it is extremely limited in its willingness to accommodate British political arguments that it neither understands nor respects. Maybe the EU should have done more to prevent Brexit, but it didn’t, because that’s not what the EU does.

So when EU leaders say Theresa May’s deal is the best and only deal available, how should Britain respond?

You’d expect evidence-allergic Leavers to scoff and urge May to call the Europeans’ bluff, because they cannot understand that as far as the EU27 is concerned, the game is over because Britain chose to throw away its cards in June 2016.

Sadly though, the belief that the EU is bluffing is now widespread on the Remain side of politics too. Significant numbers of Remain-minded Tory and Labour MPs will, as things stand, vote against the May deal next week. Many argue that doing so leads to better outcomes (a better deal, a second referendum, no Brexit) but none is able to explain the process whereby those outcomes are actually reached.

Many take comfort in the nostrum that “there is no majority in the Commons for No Deal”, which is true but not the whole truth, since the Article 50 process means that all that is needed for Britain to fall out with no deal is for MPs to go on failing to agree on anything else. The superstition of the Remainers is essentially the same as that of the hardline Leavers: if we threaten to shoot ourselves in the head, the EU will put its gun down and give us what we want. In fact, the gun is loaded and cocked and it will go off on 29 March next year. All that remains to decide is which way it’s pointing when the trigger is pulled.

As a Remain-voting pragmatist, I find it especially saddening to see smart, sensible people such as Jo Johnson and Sam Gyimah lining up to reject the May deal on basis of faith that afterwards, something better will turn up. This is, to quote Voltaire and Michael Gove, to make the best the enemy of the good. Yes remaining in the EU is the best economic outcome for the UK, but both the potential political costs of doing so, and the potential economic harms of ending up with no deal, both strike me as too high to justify the risks involved in rejecting May’s imperfect deal.

MPs on all sides of the Brexit debate are currently marching gaily towards a Commons vote where they reject that deal, confident in their belief that they will get a second bite at the cherry, that such a vote will demonstrate clearly to the EU27 that Britain really does feel strongly about this stuff, so they really ought to think again and give May a better deal that she can put to the Commons again.

That belief has taken hold despite the long history suggesting that that’s not what the EU does. Despite the fact that the EU wasn’t prepared to bend to accommodate Cameron and keep Britain in. Despite the Brexit negotiations during which the EU27 have remained united behind a strategy that prioritises the Four Freedoms above protecting Britain’s politics or economy from the consequences of Britain’s decision to leave. Despite the evidence.

We are leaving the EU because the EU doesn’t blink. The Brexit negotiations reached the conclusion they did because the EU doesn’t blink. Now, with a No Deal exit that would hurt the UK much more than the EU less than four months away, MPs on all sides seem to have convinced themselves that the EU is about to blink. That this time is different.

History doesn’t always repeat itself. Sometimes things do change. Perhaps the EU really will make a new and much better offer to Britain if the Commons rejects the May deal. Maybe this time really will be different.

But any MP preparing to vote against the deal on the basis of a superstitious belief that doing so will improve Britain’s choices should ask themselves one question first: what if you’re wrong?

Comments