A contributory factor to the continuing impoverishment of Britain is psychiatric diagnosis – or rather, the superstitious official belief in it.

More than two thirds of Incapacity Benefit claims over the space of two years were for supposed psychiatric conditions. Psychiatric diagnosis has produced more invalids than the first world war. It is the foundry in which the mind-forg’d manacles are produced – mass-produced, in fact.

The most common diagnoses – of depression and anxiety, for example – are completely dependent on what the patient tells the doctor. The doctor’s default position, quite rightly, is to believe what his patients tell him. Failure to do this can lead to disaster, besides which he has little time to investigate further. Moreover, questioning of any kind often appears to the patient to be first disbelief and then accusation, which may call forth anger and resentment, complaint, aggression, or even violence. The easiest and quickest thing for the doctor to do is to accede to what he assumes the patient is asking for. There will then be no unseemly scenes in the surgery or consulting room.

Belief in what the patients say works very well where patients are mostly honest with others and themselves. Unfortunately, the concept of mental health has undermined this honesty and where people can derive benefit from feeling anxious and depressed – or saying that they do – they will claim to be such. The supply calls forth the demand, the reward the effort.

The situation is more complex than that of straightforward fraud or lying. Both anxiety and depression are normal features of life, except in the most severe forms, and in fact activity is one of the ways in which they may be overcome. Unfortunately, they have been medicalised to the point where any degree of them is regarded and then treated, both by the patient and the doctor, as pathological.

Outright fraud exists, of course, and it is probable that the NHS stands more in need of private detectives than psychotherapists, to check the authenticity of claims to mental incapacity. I remember legal cases in which claimants who allegedly could not get out of bed because of their illness nevertheless made it to Brazil or South Africa on holiday. They resolved this apparent contradiction by claiming they had their good weeks and their bad – and, incidentally, they were believed by the courts.

But outright fraud is not the whole problem. The fact is that if you believe yourself to be or to act something long enough, that is what you become. A belief in illness feeds on itself, as was pointed out long ago in a song by Stanley Holloway. In the song, the barmaid tells him he looks unwell:

My knees started knocking, I did feel so sad.

Then Brown said, ‘Don’t die in a pub, it looks bad,’

He said, ‘Come with me, I’ll show you what to do.

Now I’ve got a friend who’ll be useful to you.’

He led me to Black’s Undertaking Depot,

And Black, with some crepe round his hat said, ‘Hello,

My word you do look queer!

My word you do look queer!

Now we’ll fix you up for a trifling amount.

Now what do you say to a bit on account?’

I said, ‘I’m not dying.’ He said, ‘Don’t say that!

My business of late has been terribly flat,

But I’m telling my wife she can have that new hat!

My word, you do look queer!’

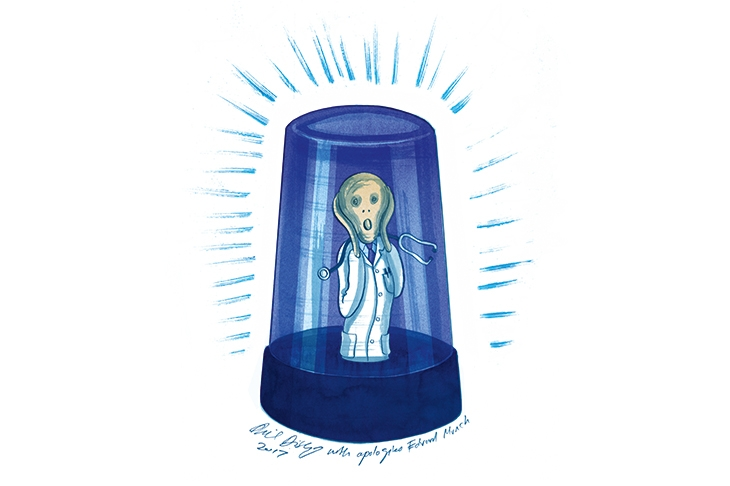

This captures the way in which the belief that you are ill leads to feeling ill, as well as the vested interest in the psychological fragility that has been encouraged. As the Viennese satirist, Karl Kraus presciently put it, psychoanalysis is the disease it pretends to cure. There is an equal and opposite effect, however:

I crawled in the street and I murmured, ‘I’m done.’

Then up came Old Jenkins and shouted, ‘Oh son!

My word you do look well!

My word you do look well!

You’re looking fine and in the pink!’

I shouted, ‘Am I?… Come and have a drink!

You’ve put new life in me, I’m sounder than a bell.

By gad! There’s life in the old dog yet.

My word I do feel well!’

Our current belief in the chimera mental health is the sovereign means of turning fraud into illness and illness into fraud. This is no small matter: it cost billions, increases misery, and brings forward encroaching poverty, not only for individuals but for the whole country.

Comments