Journalists rarely had it so easy as when it came to writing up the final result of the French presidential election on Monday morning. The copy almost wrote itself: the triumph of moderation, demonstrated by a convincing win for centrist Emmanuel Macron over his far-right challenger Marine Le Pen; the clear defeat of disruptive extremist politics that might otherwise have threatened European stability; and the return to EU business as usual, with euroscepticism once again off the table and the re-establishment of a stable Franco-German axis in charge of Brussels.

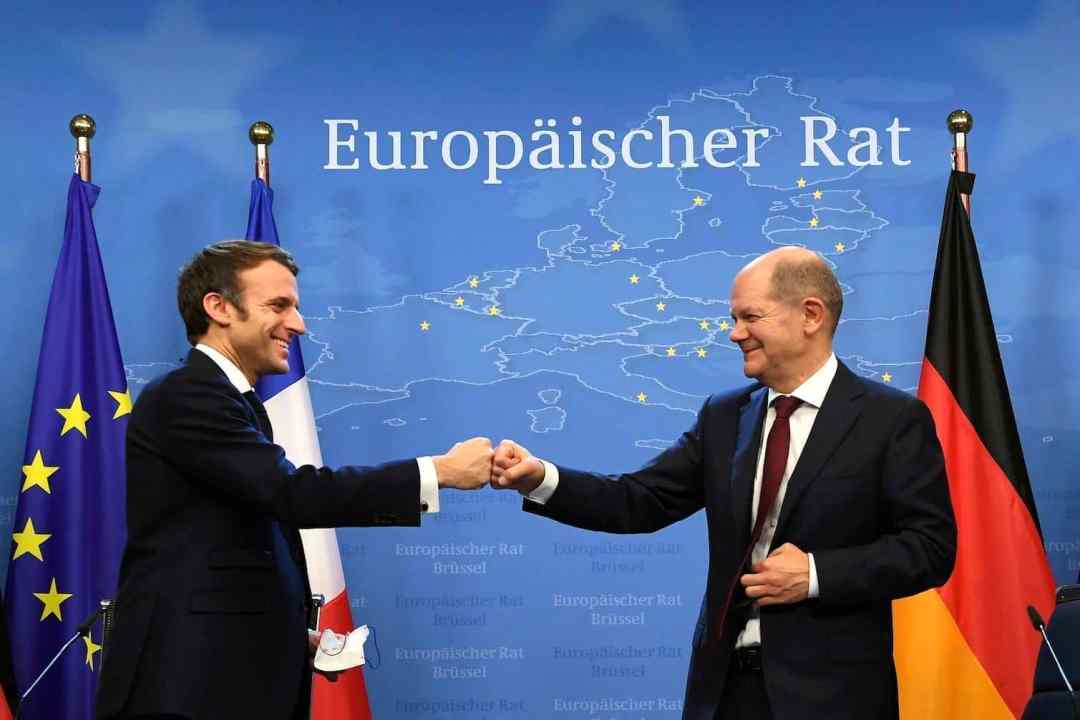

Easy, but ultimately unconvincing. Centrists who can be trusted not to be too radical may indeed be in power in France, as they have been in Germany since the installation of Olaf Scholz as Chancellor late last year. However, it is hard to see that this is due to any particular enthusiasm from voters. The vote in France was on a historically low turnout for les présidentielles (some 28 per cent, well over one in four, stayed at home). Macron’s eventual victory, moreover, was well down from his performance in 2017 when he beat Le Pen by two to one.

There is another uncomfortable fact: in the first round over half the votes went to candidates with colourful policies who on no account were centrist. Le Pen (socially conservative but economically redistributive) on 23 per cent was very closely followed by socialist firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Behind him, genuine reactionary Eric Zemmour on 7 per cent humiliated the once-unstoppable Gaullists, who scored less than 5 per cent. Macron’s victory seems to have been at least partly due to election weariness, and the fact that many of those – by some accounts nearly half – who previously opted for Mélenchon and other candidates simply stayed away.

At one time centrist politics in Europe had a tinge of nationalism that voters could identify with

So too elsewhere. In Germany, Chancellor Olaf Scholz is an emphatically colourless employment lawyer elected to lead the leftish SPD while serving in Angela Merkel’s government; he only got the job because after an inconclusive 2021 poll he managed to cobble together a slightly improbable coalition with the Greens and the radical free-market FPD. In Italy the economist and technocrat Mario Draghi, an ex-EU apparatchik, was not voted in by anyone. Instead he was appointed a little over a year ago after protracted horse-trading between the fissiparous groupings that form the chaotic if ever-changing backdrop to Italian national politics.

Nor is the lack of enthusiasm for expressed centrism confined to western Europe. In Hungary earlier this month, the electorate was offered on a plate the ideal new European centrist: a candidate promoting liberal democracy and EU enthusiasm, and armed with the unequivocal seal of approval of both Brussels and the entire liberal establishment. They were having none of it. Despite exuding sweet centrist reasonableness from every pore, he was roundly beaten by Viktor Orbán by a margin convincing (even once one takes into account possible unfairness in the election process).

Why? The answer, I suggest, is that the idea of political centrism has subtly changed. At one time centrist politics in Europe had a tinge of nationalism that voters could identify with. The Gaullists in France were not just a slightly conservative party that avoided extremes of left and right, but a visibly nationalist grouping, supportive of the traditional Napoleonic French view of the state and the municipality as an integral part of every citizen’s life, and prepared where necessary to fight France’s corner in the EU and elsewhere. And even in Germany there was something of the same. After the fruition of the obviously nationalistic unification project under Helmut Kohl in 1990, most politics in Germany remained recognisably pro-German. It encouraged the increase of German prosperity and high employment through a policy of giving German industrial and commercial enterprises the best opportunities to expand their exports to the rest of Europe – even where this included maintaining the Eurozone at the expense of other member states, and more recently in keeping uncomfortably close relations with unpleasant regimes such as Russia.

No longer. Today the essence of centrism seems not so much non-extremism, but the lack of any noticeable ideology at all. In the French election, we heard much about the policies of Le Pen, Mélenchon and Zemmour, but almost nothing about Macron’s. Apart from vague references to reindustrialisation and restoring prosperity to French workers, his selling point was, essentially, his lack of any specific platform. He wasn’t Le Pen; he wasn’t beholden to Russia; and he wouldn’t make difficulties of the EU and its increasing control over the internal politics of individual countries in Europe. Like other European leaders such as Scholz or Draghi, he made a virtue of being the safe, colourless, candidate to vote for if you wanted to avoid rocking the boat. Like them, the very model of a modern major centrist, he could be described as a kind of zombie statesman: a politician malgré lui, prepared to leave the running of the state to technocrats and supranational organisations such as the EU.

This rather denatured political model worked on this occasion. But will it continue to attract European voters? There are signs that it may not. The rise in voters choosing politicians with more radical policies, whether right, left or (in the case of Le Pen) a combination of the two, does not bode well for it. Next time round a politician may well be unable to coast to victory, whether in France or elsewhere, by simply avoiding saying anything of interest.

Indeed, an aspiring European politician might even look across the Channel. Boris is actually a centrist, though unlike the European variety far from an anodyne one. Unashamedly nationalist and pro-business, socially liberal and receptive to the active state, he is not afraid to say what he thinks. And, despite gaffes like partygate, he has been a successful model with voters.

True, the European could choose instead to imitate Keir, who for his part is surprisingly like Macron: overtly competent, faintly charming, colourless and non-committal, and with no policies that most people could name, let alone be offended by. But should he follow that route? One rather doubts it: since Keir’s hopes of beating Boris still turn largely on capitalising on Boris’s errors rather than on his own particular attractiveness to voters, this would be, to say the least, a high-risk strategy. Far better, one suspects, to assume that the days of saying nothing and simply hoping for the best are unlikely to last, and approach the voters accordingly.

Comments