In 1979, XTC sang: ‘We’re only making plans for Nigel/ We only want what’s best for him.’ The song is from the perspective of two overbearing parents, confident that their son is ‘happy in his world’ and that his future ‘is as good as sealed’.

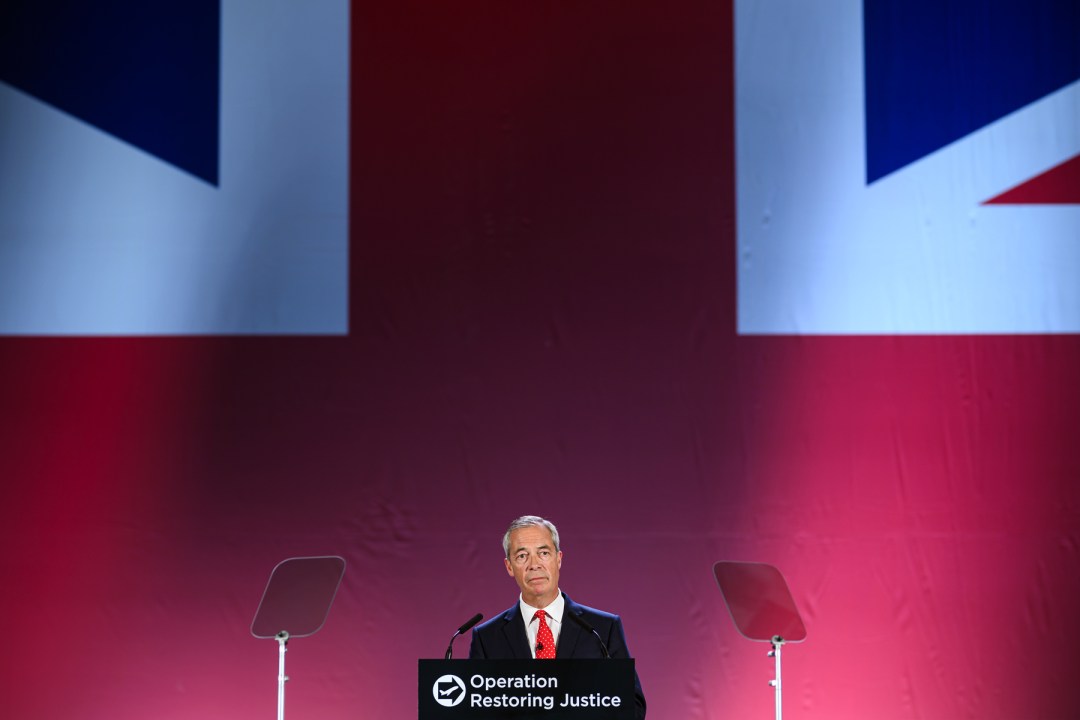

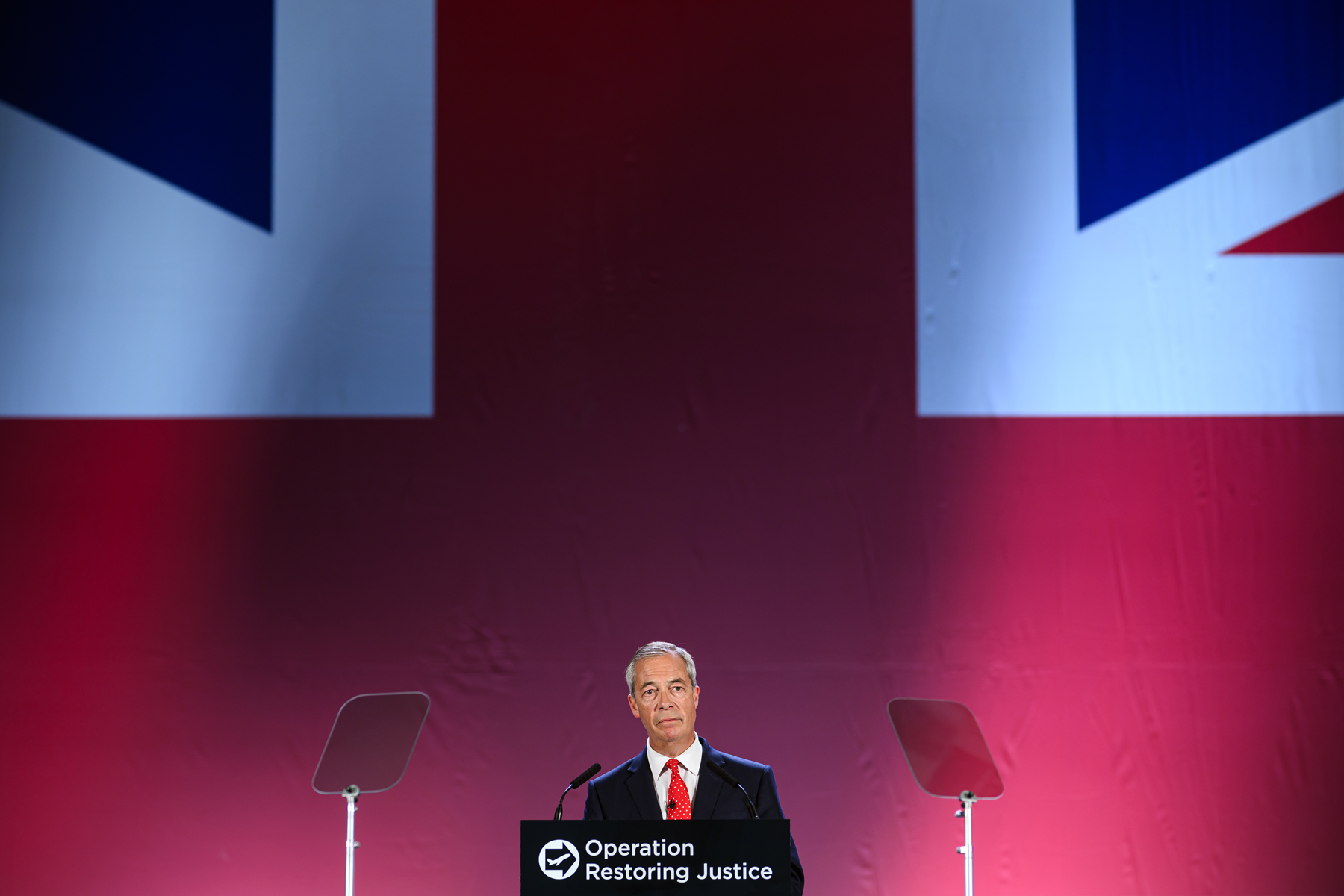

Nigel Farage is making plans for his own future but it’s doubtful it’s as good as sealed. This week, he announced Reform UK’s proposal for mass deportations, ‘Operation Restoring Justice’. Some 600,000 illegal migrants will be removed, he promised, should his party win the next election. Britain will leave the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) so we can return people to countries such as Afghanistan and Eritrea, currently deemed too dangerous. Military bases will be converted into detention centres, holding up to 24,000 deportees. A new UK Bill of Rights will replace international treaties, and the migration crisis will be enshrined in law as Whitehall’s top priority.

Some of these measures are familiar. The Bill of Rights is an idea the Tories have been discussing for decades. David Cameron said during the 2010 election campaign that he wanted such a bill to replace the ECHR. Reform also plans to revive Rwanda as a location for migrant-processing. The implication is that Farage is the true inheritor of the right, able to do what Conservative governments couldn’t.

It is the Tory party’s fault that such a notion even sounds credible. In 2019, it promised to reduce immigration. Instead, legal levels tripled and the boats continued to cross the Channel. Last year, Labour promised to ‘smash the gangs’. But crossings are now running at record levels, with more than 28,000 migrants having arrived in small boats this year. Voters are fed up. For those wishing a plague on the old order, Farage is the obvious answer.

Yet, as adept as he is at channelling disillusionment, Farage has no experience of office. For some, this is part of his appeal. But it also means he’s never been held accountable. He’s never run a department, overseen legislation, made good on a pledge. Even Brexit, the cause to which he devoted a quarter-century of his life, was enacted by the Tories he seeks to bury. Farage as Prime Minister is a serious prospect. But can he – and his party – be taken seriously?

When Farage speaks about areas beyond immigration, he displays a worrying financial recklessness

To deliver his policies, Farage would have to take on the Whitehall inertia, establishment resistance and legal constraints that have frustrated successive governments. Even Keir Starmer’s chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, has complained that Whitehall is dysfunctional. As Tim Shipman revealed in this magazine, McSweeney told the Prime Minister: ‘We must be insurgents from the outset… Voters understand perfectly well that the British state is broken and in need of radical reform.’

If Farage were to enter office, he would do so because Labour has failed an electorate that is rightly angry and impatient. An inability to grasp the machinery of state and demonstrate results quickly would mean suffering the same fate as every government for the past decade. If Reform flounders, British democracy would face a crisis of confidence. What – or who – comes next?

The records of the ten Reform councils elected in May are mixed. Some pledges have been fulfilled. Net-zero posturing and diversity initiatives have been removed. But councillors have found themselves obstructed by obstreperous officials and costly statutory obligations. Others have been distracted by less pressing issues. Lancashire County Council requires £103 million in savings to ensure solvency; instead the new Reform councillors have spent much time trying to remove Pride flags from county buildings.

When Farage speaks about policy areas beyond immigration, he displays a worrying recklessness with the public finances. He has pledged to take the steel and water industries into public control, to repeal the two-child benefit cap and to take millions of people out of income tax. This shows a failure to recognise the country’s perilous fiscal situation, which Michael Simmons outlines. It is not a time for writing budgets on the back of fag packets.

As well as XTC’s hit, 1979 saw the election of Britain’s last transformative right-wing government. In opposition, Margaret Thatcher commissioned the document ‘Stepping Stones’, an analysis of Britain’s postwar decline and of her predecessors’ failure to overcome it. The conclusion was a detailed set of actions that had to be taken to avoid those same failures. To match Thatcher’s success, Farage will need a similar strategy.

A Reform victory should mean not just a change of government party but a fundamental transformation of the British state. Farage will need a team capable of carrying that out. Yet his list of former allies is long; even since last year’s election, he has lost two of his five MPs. Undoubtedly, Reform strives to appear as a professional organisation. But can Farage be a team player? Is there an effort to enlist talented people? Or will his party remain a hodgepodge of long-standing groupies, Tory cast-offs, pubescent councillors and D-list celebrities?

Farage can count on goodwill from many on the right who want him to succeed. But Reform requires a plan not only for what the party wants to do in government, but also for how to deliver it.

Comments