Mutilated, strangled, suffocated or beaten to death: these are just some of the methods used to get rid of popes in the early medieval period. An incredible 33 per cent of all anointed popes between 872 and 1012 died in suspicious circumstances. It’s safe to say that the path to Christian dominance in Europe was rocky at times.

Peter Heather’s revisionist history of the rise of medieval Christendom directs attention to these moments. Though the subtitle is ‘The Triumph of a Religion’, his account is anything but triumphalist. In fact his argument gains momentum through the challenge it poses to simplistic accounts of Christian ascendency.

Pope Gregory the Great forced his peasants to convert to Christianity through threats of rent rises

The dominant historical narratives written in 20th-century Britain went like this: Christianity spread from Palestine across Europe from the 4th century onwards, through a gradual, constant process of personal conversion, underwritten by the truth of Christian doctrine. By contrast, Heather explores the pragmatic, administrative ways in which Christianity gained power. This is not to say that he downplays the significance of individual belief, but he reminds us to consider the leap from private spirituality to an institutional, hegemonic ruling system. It is the latter which is his subject: Christendom as a political entity, with a hold across the European continent.

The link between Christianity and Europe continues to define global politics. Heather destabilises this link at its origin, showing how Christian supremacy was far from inevitable, and how state power shaped the trajectory of the religion. As such, although this is definitely a book which will be useful to anyone who wants to tell their Visigoths from their Vandals, the relevance of the author’s argument demands a much broader audience. Taking a long view of history, Heather allows the reader to witness the development of Christianity in a context of supreme imperial command to its survival in the chaos of ‘the Christian commonwealth’.

Beginning with the conversion of the Emperor Constantine in the year 312, he argues that Christianity became a de facto branch of the Roman administration. It was this intersection with state power that transformed the religion from ‘a small, Near Eastern mystery cult’ to a mass movement. Heather shows how conversion to Christianity within the Roman system didn’t require violence to be coercive. There was intense pressure for individuals to conform in order to survive and thrive. It is a convincing argument, which resonates with later histories of conversion and empire. We are shown in meticulous detail how elite provincial landlords across the Roman empire converted in order to gain imperial favour, bringing their tenants with them into the faith.

This account of the spread of Christianity makes for a suspenseful set-up for the second part of the story: its fate after the fall of the Roman empire. Heather turns a dense web of provincial rulers and confusing successions of power into a compelling narrative as we follow the reinvention of Christianity for a post-imperial age. He shows how Christianity was adapted as it spread to new regions of Europe, to encourage its adoption among the locals. For example, the early medieval north European church revised its principles to be lenient towards killing in reflection of the priorities of newly converted warriors. The role of landlords in the dissemination of the faith remains a striking theme across history: in the 6th century we see how Pope Gregory the Great forced the peasants on his land to convert through threats of rent rises.

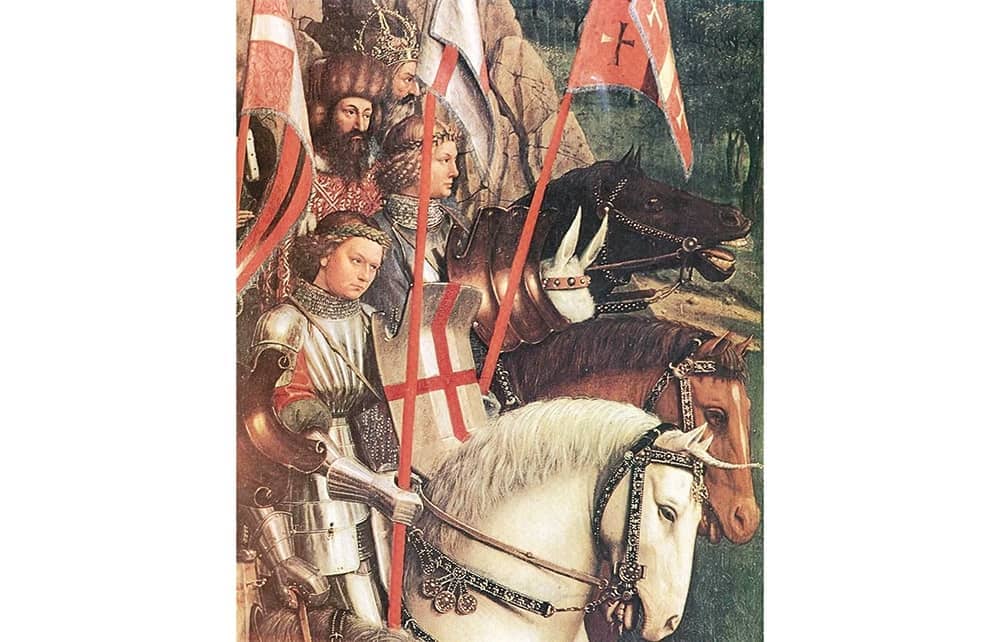

The final part sees the development of a one-party style of Christian rulership, where papal doctrine was enforced across Europe through direct intimidation and a climate of fear. By the 12th century it was the locals who were expected to change, not the church. A system of largely autonomous communities was brought together into a superstate, a single corporate entity whose influence on the course of history cannot be underestimated. The unlikely ‘success’ of the First Crusade, with the Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, enabled the solidification of Christian dominance. The idea of a Christian Holy Land was a propaganda image which proved irresistible to many – which was lucky for them, since resistance would have put them in the hands of the Inquisition.

At a time when Victor Orbán speaks of the need for Europe to ‘return to its Christian identity’, it is more pressing than ever to understand how exactly Christianity came to dominate in Europe. Heather’s account cuts through the myth of an innately Christian, culturally monolithic Europe. Rather than leaving us with a sense of the glorious achievements of ascendency, Heather sheds light on the mechanics of state coercion and intermittent violence which led to the birth of Christendom. It’s no light reading – but there’s enough drama to make it a page-turner.

Comments