Funny old life, eh? Small world, etc. In one of those curious, Alan Bennett-y, believe-it-or-not-but-I-once-delivered-meat-to-the mother-in-law-of-T.S.-Eliot-type coincidences, it turns out that Mark Knopfler once worked as a copy boy on the Newcastle Evening Chronicle when Basil Bunting was working there as a sub-editor. Knopfler being Knopfler, he eventually wrote a sad sweet song about it, ‘Basil’, in which he describes England’s most important modernist poet sitting stranded in the newspaper offices, surrounded by up-and-coming Bri-Nylon-clad jack-the-lads, wearing his ancient blue sweater, puffing on his untipped Players, clearly ‘too old for the job’ and ‘bored out of his mind’. ‘Bury all joy/ Put the poems in sacks/ And bury me here with the hacks.’

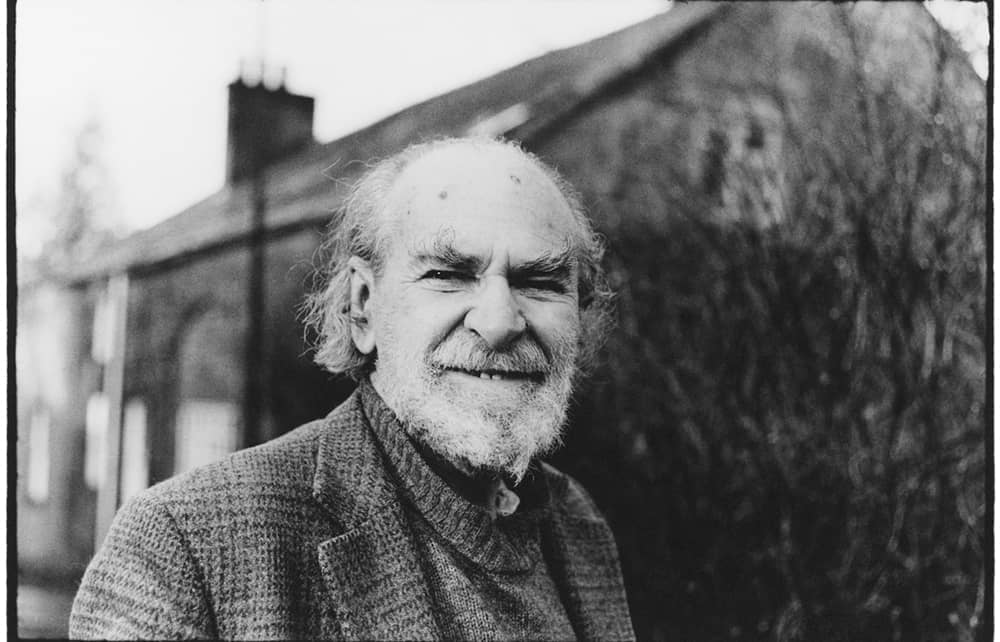

Good old/poor old Basil: the sweater-wearing, sharp-bearded Bunting is periodically disinterred by poets and scholars seeking out alternative histories of English verse in which the off-beat, the eccentric, the experimental and the downright odd are shown to truly express and characterise the national spirit rather than the usual bland mainstream pap.

The academic and poet Alex Niven – one of the UK’s rather more interesting younger cultural critics, the author of both New Model Island: How to Build a Radical Culture Beyond the Idea of England (2019) and a short book about Oasis’s Definitely Maybe – now adds to this history with a selected edition of Basil Bunting’s letters. In his introduction to the volume, Niven acknowledges that even during his lifetime, Bunting was a ‘relatively unknown figure’ and that there is a ‘gappiness’ to the correspondence. Gappiness is well put – and a bit of an understatement. In both Bunting’s letters and the poetry there are years of billowing nothing. But what is there is remarkable and certainly deserves to be added to the alt. Eng. Lit. canon.

His sad, extraordinary life was the sort you want a writer to live but wouldn’t necessarily want to live yourself

For those unfamiliar with Bunting, it’s probably worth noting that he led both a rather sad and most extraordinary life, the sort of life you want a writer to live but wouldn’t necessarily want to live yourself. Imprisoned during the first world war as a conscientious objector, he studied at the LSE, worked as a life model in Paris and as an assistant editor to Ford Madox Ford at the Transatlantic Review. He later moved to the Canary Islands, bought a boat and sailed to America, where he worked as a seaman, and then somehow ended up after the second world war as head of British intelligence in Iran, before becoming a special correspondent for the Times. He eventually returned to England, working at the Chronicle in Newcastle – with the teenage Knopfler – where he finally achieved a little fame and notoriety for his poem ‘Briggflatts’ (1966). It was heralded by the counterculture crowd who had gathered around Tom and Connie Pickard’s poetry readings at a place called Morden Tower, which is an actual medieval tower in Newcastle and one of the few true landmarks in postwar English poetry.

So, Bunting did a lot of interesting things. And ‘Briggflatts’ – with its famous opening lines, ‘Brag, sweet tenor bull, / descant on Rawthey’s madrigal’ – is certainly a great poem. But for all his achievements, it has to be said, on the evidence of these letters, he wasn’t much of a storyteller. There are the occasional flashes of brilliance – memories of the old ‘flea-tortured St Bernard’ that used to lie outside a shop in Rapallo – but there’s also a lot of everyday low-level musing and grumbling.

What is truly notable here is the correspondence with Ezra Pound – and later with fellow poet Louis Zukofsky. The correspondence with Pound is spirited stuff, exactly what you’d expect when a no-nonsense northern English Quaker comes up against a half-crazy, self-promoting, cowboy Yankee blowhard. Fair play to Bunting, he picks Pound up on just about everything you’d want to pick him up on. In March 1935, for example, he points out some of the obvious flaws in Pound’s so-called economic theories: ‘You surely got a bloody big bat in the belfry about economics. It seems to me just one of a good number of matters that are all pretty equally wrong.’ And by December 1938 he’s absolutely had enough, beginning a letter:

Dear Ezra, No, I am sorry, and thank you: but I can’t take it. I wish I were not as much indebted to you as I am… You know as well as any man that a Jew has the same physique and a similar amount of grey matter as the rest of us. You know as well as any man that to hold one individual guilty of the sins of another is an abomination.

Bunting’s plain-speaking in his letters is not only challenging but often extremely moving, particularly when it comes to assessing his own motives and purposes. He writes in a letter to the critic Donald Davie in September 1975:

What keeps a man at it, in spite of bitter poverty, general indifference, public distaste and so on? I do not think there is any contemporary expression for what holds him to difficult work such as his, but a few centuries ago, when the world still had an admitted meaning, they might have said he did it for the glory of God.

We might well say the same.

Comments