Rend your cheeks and rub ashes into your hair; for that most elegant, elusive of punctuation marks – the semicolon – is, if not yet quite dead, at least fairly close to being on first name terms with St Peter. Research from Babbel, a ‘learning platform’, shows that usage of the semicolon in texts has plunged by 47 per cent over the past two decades. I would be more surprised if the Pope turned out to be Catholic. These days, students struggle with commas and apostrophes. How can the poor milquetoasts be expected to grasp the finer usages of semicolons?

This is all a terrible shame. Good punctuation is a balm for the soul. As punctuation (or ‘pointing’, as it used to be called) orders sentences, so this relates to the order of mind, body and the universe itself. I do not exaggerate; Cicero himself thought so.

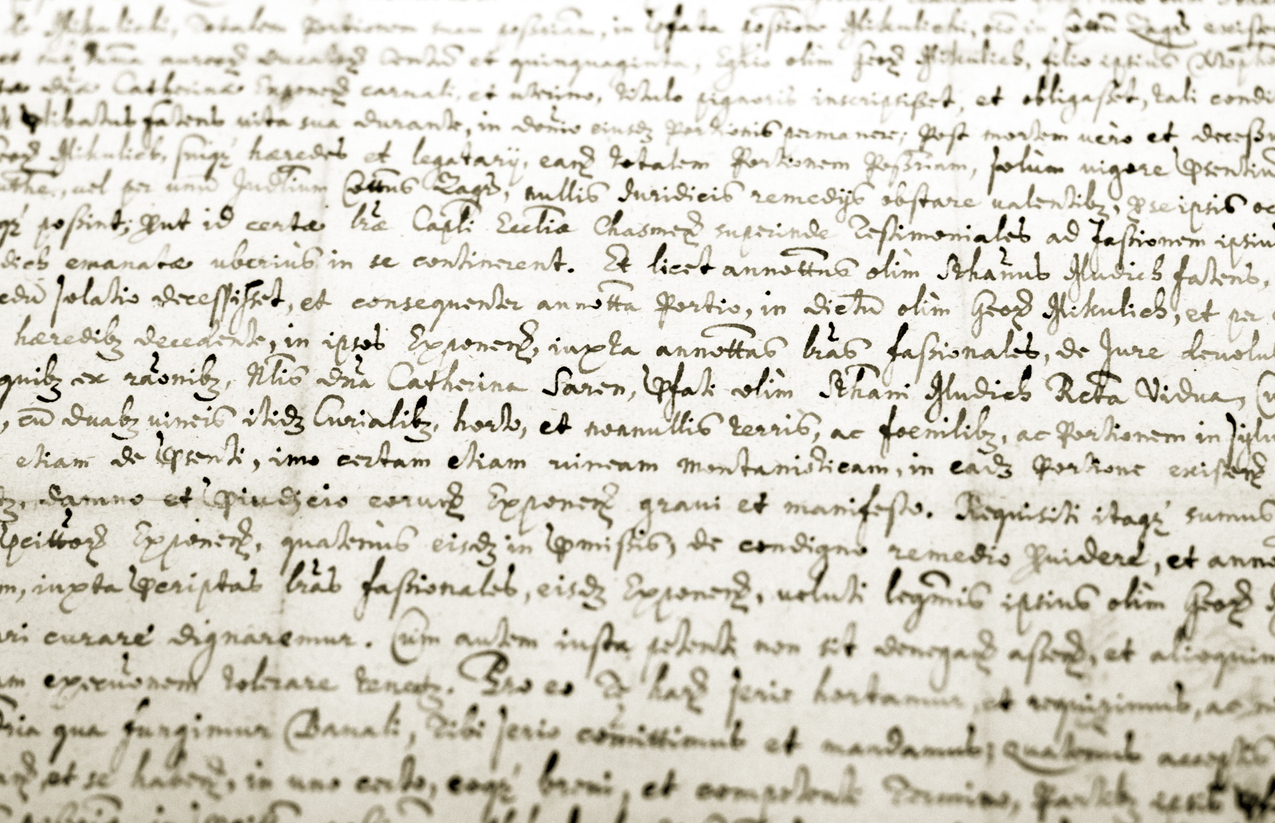

We can thank Aldus Manutius for introducing the semicolon into Venice, in the 1490s (though its previous life, in Ancient Greek, was as a question mark). What better birthplace than La Serenissima? Where brackets, or lunulae, remind us of the moon, simply using a semicolon in a sentence links us to gondolas, to the Bridge of Sighs; to sunlight shining on the waters of the canals. The typesetter Nicolas Jenson used a star in place of the point; I wish this had become common usage. Its first appearance in English – its debut, perhaps – came in the highest possible authority: the Coverdale Bible, printed in Paris in 1538.

Sure, Theodor Adorno thought it looked like a drooping moustache, but I disagree: formed, from two other punctuation marks, it is a gorgeous, enigmatic, humanist chimera. It more closely resembles a gentleman, on the edge of his chair, leaning slightly forwards, poised to hear the aphorism fall from your learned lips. It is the jewelled hand, held out to be kissed; it is the tactful recognition of a guest in the glittering salon.

This, I’m afraid, is why modernity despises the semicolon. It is too courtly, too refined, too subtle. I blame the democratic, cow-steering Americans, who shun it. They think of it as King Lear did the letter zed: unnecessary. For them it is a foppish aristo sipping absinthe, while the plebeian comma sweats beneath. Computers can’t stand it, because its proper usage refuses strict rules. Deploy it and their horrible, bossy ‘writing’ programmes become confused. (Which, to my mind, is more than reason enough to carry on with them.)

Indeed, the semicolon is useful, unlike the poor old punctus percontativus, ⸮, or rhetorical question mark, which vanished along with ruffs. Who needs a mark to tell us a question is rhetorical, I ask you⸮

The semicolon’s role, on the other hand, is manifold. It is caesura; it is release mechanism; it both divides, and connects

The semicolon’s role, on the other hand, is manifold. It is caesura; it is release mechanism; it both divides and connects. ‘It was the best of times; it was the worst of times’ is rendered much better with a semicolon. Witness this gorgeous specimen by Christopher Marlowe, in ‘Hero and Leander’:

Come thither; As she spake this, her toong tript.

For vnawares (Come thither) from her slipt.

And sodainly her former colour chang’d.

And here and there her eies through anger rang’d.

That slight, erotic pause after the first ‘thither’; it’s heavenly. Daniel Defoe’s usage of the semicolon threw Samuel Taylor Coleridge into raptures. When Robinson Crusoe returns to his ship for the final time, he finds a large amount of gold; now all useless and for a moment he wants to let it sink with the ship. Defoe then writes: ‘However, upon second thoughts, I took it away; and wrapping all this in a piece of canvas…’ For Coleridge, this semicolon was ‘exquisite and masterlike… A meaner writer… would have put an ‘!’ after ‘away’. It rendered Defoe, he said, on the same level as Shakespeare. (Incidentally, the original Robinson Crusoe doesn’t have a semicolon there, since it was inserted by a later editor. But still, the point, if you’ll excuse the pun, holds.)

We must resist this decline. Like napkins, black tie and having a glass of champagne before lunch, the semicolon remains a bulwark against civilisational decline. We mustn’t let a generation ape the meaner writers (!) Pause, rest, think; and encourage this most noble of punctuation marks to flourish anew.

Comments