In this book about courage, Polly Morland talks to lots of people who should know what it is. She talks to soldiers, surfers, a matador, firefighters and professional daredevils. She interviews a man who fixes the upper sections of skyscrapers, and is afraid of heights. She meets people who have been diagnosed with terminal diseases. She quizzes a former armed robber. It’s well worth reading. Morland is slightly more humanistic than scientific; she wonders what courage is, without being absolutely determined to come up with a definition.

I started the book thinking that courage is the ability to do something you think is right, even when you’re scared. It means not wavering from your core beliefs, or feelings, when things get difficult or dangerous. Think of the word core. Think of the French word coeur. It’s all about heart, about solidity, about being firm and steadfast. When you think about it like this, it seems to be a rather conservative thing; it even has something in common with being stubborn. Of course, being stubborn is a good thing, if you’re right.

Morland interviews Colonel Tim Collins, famous for the eve-of-battle speech he gave British troops in Iraq in 2003. He says that, before you go into battle, you close certain doors in your mind. Then, when you come back, it’s not easy to open them again. Which suggests that, in one sense, you can learn how to be brave — you can, as it were, pre-set your controls. So when the crucial moment arrives, when you need courage, it’s already there; it’s not a matter of girding your loins against novel terror, but more like following a programme. Perhaps the moment of courage happens while you are pre-setting your controls; this is where the real sacrifice occurs.

Strong hearts, girded loins — it’s hard to separate the idea of courage from the idea of the body and its vulnerability. And wounds loom large in this book. In one of the best sequences, Morland tells the story of a group of British soldiers in Afghanistan. One is blown up in a minefield and loses his legs. The next day, others must retrieve his mine-detecting equipment, to keep it out of enemy hands. Three soldiers move slowly into the minefield. They have one mine-detector between them. One guy finds a severed leg. ‘He wrapped it in plastic and put it in his rucksack.’ Then another mine goes off; the man with the mine-detector loses his legs.

Three men in a minefield. One: legless, and ‘bleeding out’. The other two: rooted to the spot. The senior man tells the junior man to stay still while he creeps back out of the minefield and returns with more equipment. But the other guy, Private Martin Bell, can’t bear to do this. He disobeys the order. He walks across the minefield. He applies tourniquets to the wounded man’s legs. He saves his life. Having done this, he steps on a mine. And is killed.

Martin Bell’s act was against orders. He gambled. He lost the gamble. But he saved his friend’s life. This, surely, is the most courageous act in the book, I thought. Bell had time to think, and took a risk. But what he did was not conservative — it was, in most ways, the opposite of conservative. It was, as Morland points out, doing the wrong thing, in order to save a life. Bell won the George Medal, posthumously.

Now I’m confused. Courage is sticking to your guns. But it’s also taking a calculated risk on the spur of the moment.

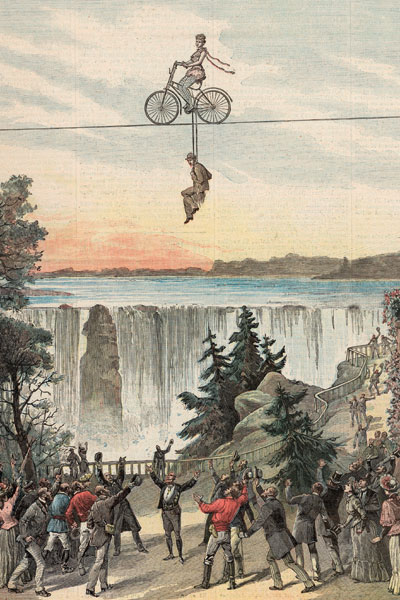

Certainly, it’s the ability to wrestle with fear, and win. Morland introduces us to people who are terminally ill, and getting on with life as best they can. That’s courage. But then she also introduces us to people who don’t just face down fear, but who live for it. What about those surfers who yearn to ride monster waves, relishing the danger? What about Alain Robert, the French guy who climbs to the top of skyscrapers without any ropes? Or the famous daredevil Dean Potter, who appears to need fear in order to feel alive?

Well, these people might not be displaying courage, but a related quality we call bravado. And some might be addicted to danger in the way other people are addicted to drugs. Fear makes you focus. When you focus, you block out your demons. When you face fear and win, you feel high. You can see why some people love fear. And why the concept of courage is so confusing.

Morland is clear about one thing. Of all the virtues, courage is, culturally speaking, the most resilient. We all love courage, and hate the lack of it. After all, when people do evil things, we have no hesitation in calling them cowards.

Comments