It was the phrase ‘sad sweet feeling in your heart’ that arrested my attention. But who would have thought it would have been Abraham Lincoln who found those words?

I’ve been searching for an adequate description of something we’ve all experienced but which is rarely discussed. Many years ago, beachcombing for pithily disobliging quotes for Scorn, my anthology of insult and invective, I was arrested by a remark of Samuel Johnson’s. ‘Depend upon it,’ Boswell quotes the great man as saying, ‘that, if a man talks of his misfortunes, there is something in them that is not disagree-able to him; for where there is nothing but pure misery, there never is any recourse to the mention of it.’

As ever, Dr Johnson pinpoints a truth with accuracy but perhaps cynicism: enough cynicism for me to include his remark in my collection. Yet it keeps coming back to me: more interesting than as just a sharp-tongued reference to the pleasures of wallowing in self-pity. Why did I so often hear friends and relations talking with great sadness about those they had loved and lost, yet never hear my grandmother mention the dreadful death of her tiny daughter from meningitis?

Never except once. I had asked her what music she liked. She replied that she stopped listening to music when her little girl was taken from her, because anything beautiful now made her sad. Then she changed the subject, which was never raised again. Poor Grandma, for whom the daughter had not had time to grow to be a friend, knew only what Johnson calls ‘pure misery’ from her loss.

Behind the archness, I think the great lexicographer was hinting at the difference between the sorrow that remains pure grief, and the sorrow that can nourish. I’ve kept up this column for more than 20 years now, and no essay I’ve written here has met more fellow-feeling from readers than one I wrote not long after the death of my father.

I decried the idea that the death of someone close was something we should ‘get over’ or ‘come to terms with’. If you have known and loved someone well (I said) a hole is left in your life and nothing will fill it, or ever should. The ache stays there because the person stays here. There is something right, something good, about our reaction to this kind of loss. It’s not wrong to dwell upon it.

Well, I don’t really know if Samuel Johnson meant to touch on this, but he certainly caused me to think. Has anyone described with honesty and eloquence the missing of someone that can feel right and good, and a positive thing? I looked out for such an account.

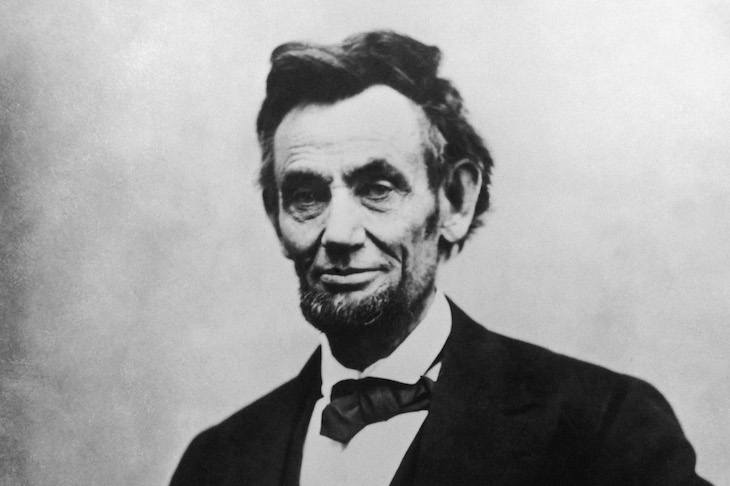

And then, researching the life of Abraham Lincoln I found, from his own pen, the right words.

The research was for a book I’m still writing which I’ll probably call Fracture. It’s anchored in an observation arising from my BBC radio series, Great Lives. Of the men and women whom my guests have chosen to champion for whatever it is they take to be greatness, I’ve been struck by how many crawled from the wreckage of truly disastrous childhoods. Lincoln is an example. His family were very poor (the ‘log cabin’ story is entirely true) and the young Lincoln was denied the education he craved, but these misfortunes were not uncommon in his day. It was not just the hardship, but his terrible relationship with a father to whom he simply couldn’t reconcile himself, and the early death of his mother (he was nine) and his beloved sister (he was 17) that broke (and made) something in him.

‘I will never forget that scene,’ wrote a relative after Abraham’s sister’s death. ‘He sat down in the door of the smoke house and buried his face in his hands. The tears slowly trickled from between his bony fingers and his gaunt frame shook with sobs. We turned away.’

The moment he reached the age of majority he boarded a flat-bottomed boat, crossed the river, and left that world for ever.

Later he wrote this:

My childhood’s home I see again,

And sadden with the view;

And still, as memory crowds my brain,

There’s pleasure in it too.‘O Memory! thou midway world

’Twixt earth and paradise,

Where things decayed and loved ones lost

In dreamy shadows rise.’

As President, Lincoln wrote to a girl, Fanny McCullough, whose father, William McCullough (an old friend), had just died.

It is with deep grief that I learn of the death of your kind and brave Father; and, especially, that it is affecting your young heart beyond what is common in such cases. In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and, to the young, it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares. The older have learned to ever expect it. I am anxious to afford some alleviation of your present distress. Perfect relief is not possible, except with time. You can not now realize that you will ever feel better. Is not this so? And yet it is a mistake. You are sure to be happy again. To know this, which is certainly true, will make you some less miserable now. I have had experience enough to know what I say; and you need only to believe it, to feel better at once.

He ends with this:

The memory of your dear Father, instead of an agony, will yet be a sad sweet feeling in your heart, of a purer and holier sort than you have known before.

I would like to think that, rather than questioning the sincerity of griefs on which we may like to dwell, that ‘sad sweet feeling in your heart’ was what Samuel Johnson was talking about.

Comments