Scottish people, known to be a bit touchy on occasion, sometimes wonder if that customary attitude of jocular condescension displayed towards their country by, in particular, the nearest neighbours, does not disguise something like envy.

Jealousy would be forgivable: as a brand, Scotland has all the trimmings: the scenery is fabulous in what Alex Salmond likes to call ‘the undisputed home of golf’, the beef and raspberries first-rate, the knitwear coveted around the globe. And as for delightful cultural inessentials, what other country of comparable or of any size can boast such a collection of instantly recognisable and authentic national signifiers?

The Royal Mile hawkers do their best to turn tartan to tat and to make Muzak out of the old, old music but when faced with the real thing, the massed pipes and drums marching past in full fig, who can resist? Likewise the ceilidh: neither granny nor toddler can dance it and leave the floor glum.

For several reasons — geological, meteorological, historical — Scottishness is just that bit more tangible — and tangy — than, say, Englishness. Alcohol — that most exquisite and precise utterance of a country’s ‘mysterious power’ — in England characteristically inhabits a pint of warm bitter, in Scotland a dram of single malt whisky. While each drink cannot but insist on its origin, the whisky’s sense of place is urgent and unignorable, the very essence of the experience of drinking it. Even if you have never been to Skye, or Speyside, or to lovely, gentle Islay (‘the Queen of the Hebrides’), images of those landscapes will begin to form in your deepest being as you smell, sip, savour Talisker, Glenfiddich, Bowmore. The produce of any distillery is so intimate with its immediate surroundings — the water, the malted barley, the smoke, the patient processes and the three years and one day (at least) that any Scotch whisky must spend maturing in oak casks in Scotland to warrant the name — that the sense you get that you are somehow drinking Scotland is no mere trick of the fancy.

It was presumably an accident by an exploratory ancient Celt which led to the discovery of whisky, and then another accident which showed the benefits of long storage in oak: however it happened, at some remote point in Celtic history this remarkable and contemplative people, forever being pushed to the fringes, inclined to defiance rather than conquest, hit on the drink which proved the perfect fit. And named it uisge-beatha, the water of life, because so it must have seemed — taste this, brother, and rejoice!

Whisky — which seems to promote both conviviality and clarity of thought, to oppose hypocrisy and privilege, to make us love the land but free us from materialism (‘Freedom an’ whisky gang thegither’, as Burns put it) — suits Scotland’s sense of herself so well that one might ask to what extent that self-image derives from the impact whisky had on it. Which came first — the whisky or the Scottishness?

That being said, the instant success of World Whisky Day (next scheduled for 17 May 2014) has emphasised that whisky is a global drink, too: Kentucky, Tennessee, Ireland, Japan, Canada and New Zealand are the other centres. Still, Scotch whisky remains the global benchmark, and easily outsells the rest (three times more than American whiskey, its nearest rival). In economic terms, Scotch is a roaring success. Exports were worth nearly £2 billion in the first half of 2013 (up 11 per cent on the same period in 2012, despite a fall-off in the Chinese market) and account not only for one quarter of all Scottish exports but one quarter of all UK food and drink exports.

Although only one fifth of this whisky is made by companies based in Scotland (Diageo owns two fifths), and it’s reckoned that just 2 per cent of the global retail sales value remains in Scotland, all the marketing material and all the politicians continue to emphasise the nationality of the product and its association with supposedly Scottish qualities.

Glenfarclas, which most unusually is still family-owned (having been in the Grant family since 1865), calls itself with justice ‘The Spirit of Independence’ but, otherwise, its publicity focuses on the buzzwords — purity, tradition, simplicity (of ingredients), uniqueness, quality, reliability, patience, complexity (of taste) — which recur whenever someone is trying to persuade you to drink malt whisky.

These words are entirely appropriate: whisky is all it’s cracked up to be and to drink it properly is to toast civilisation and culture, pay tribute to the land and nature, and do honour to the greatness and wonder of all humanity. Whisky-drinking can feel like a virtuous act.

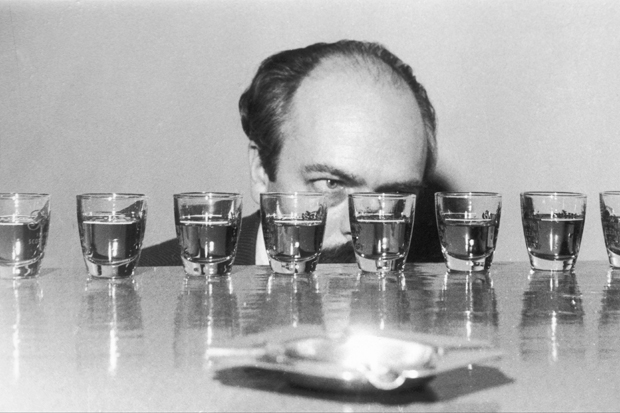

Just one wee problem: whisky is not always drunk properly. Partly because it is such a very, very good drink and some people (ahem) do not know when to stop, and partly because it is one more form that alcohol takes, whisky can lie behind some fairly capernoity conduct, and worse. However, the only reference in all the marketing and packaging to the problems that can accompany whisky-drinking is the now obligatory gentle plea, ‘Please drink responsibly’. As if we wouldn’t!

The reticence is justified. People’s personal difficulties are not the fault of the products they cling to, and the fact that Scotland has a bit of a drink problem need not be connected to her 108 licensed distilleries. (Scots drink twice as much vodka as the English.) On the other hand, the urge to oblivion is a complicated and not always enviable aspect of Scottishness, which must be addressed as the referendum approaches. Scotland is fiercely proud yet somehow humble, she is blazingly patriotic but not necessarily nationalist: she takes her time and is concerned, perhaps above all, with matters of the mind. Slàinte mhath!

Comments