From ‘Criminal Warfare and Retaliation’, The Spectator, 24 April 1915:

Although a soldier is supposed to obey his officer unquestioningly, the English soldier has two masters, his officer and the law. An illegal command need not be obeyed by the English soldier. An English soldier who kills by order of his officer is liable to be tried for murder. That obedience to two possibly conflicting authorities is obviously subversive of discipline, for it makes the soldier a judge as to whether he should obey or not. German discipline, on the other hand, makes obedience absolute, considers the soldier merely as a passive instrument executing a higher will, and makes the officer solely responsible for the soldier’s action. That is the conception of discipline and responsibility held by our enemies. A German soldier or sailor who, at the orders of his officers, murders or steals has only done his duty. A soldier or sailor who refuses to murder or steal when ordered to do so is liable to be shot without trial for disobedience in face of the enemy. The British and the German conceptions of the soldier’s duty are thus diametrically opposed. The British soldier is expected by the law to use his own judgment. The German soldier is expected to obey unquestioningly. By the German conception, the soldier has not to reason whether the orders given to him are right or wrong.

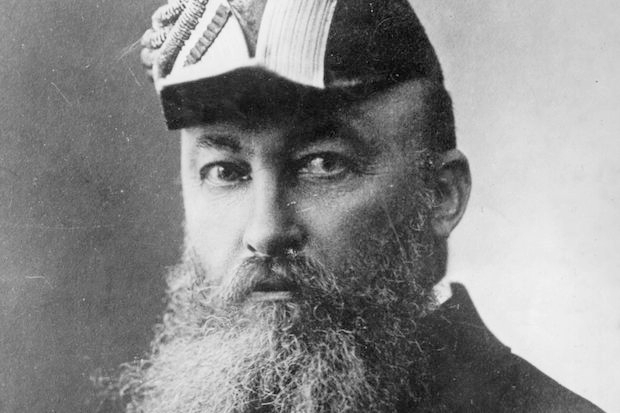

Only he who has given the order is responsible. To every German, soldier or civilian, it is inconceivable that men whose only duty consists in obeying orders should be held responsible for doing what they ought to do—their duty. If the order to sink merchantmen wore given by the Emperor to Admiral von Tirpitz and by the Admiral to the officers, nobody, according to the German conception of right and wrong, is responsible except the Emperor himself. Surely no Englishman can expect that German officers and soldiers should be acquainted with the English conception of right and wrong, and regulate their conduct by standards with which they may not be acquainted. It is sincerely to be hoped that the demand for retaliation against German prisoners will be disregarded. For if it comes to a game of mutual retaliation, English people can never go as far as Germans. In view of German methods, we can have little doubt that the German authorities would not shrink from any crime in the name of retaliation, and that they would not hesitate to starve or kill their prisoners.

Retaliation is not a game that two can play at if England is one of the two. It is a game at which we are sure to be beaten. We should, indeed, start beaten, and badly beaten. We must, of course, not show fear of German retaliation, but keep calmly on our way, content to do right while others do wrong. One thing, however, we must avoid, and that is giving Germany any more excuses for reprisals such as Mr. Churchill gave them by his order in regard to the submarine crews. No doubt he only meant to mark his disgust at German brutality, and no doubt also no submarine prisoners have suffered any cruel treatment owing to the order. Unfortunately, however, he has provided the Germans with an excuse for treating selected officers with cruelty. It was a blunder, and one which we must be careful not to repeat.

The only permissible form of retaliation is well illustrated by the inscription which, according to Wednesday’s Daily Express, a Streatham gardener has placed on a brooch which he has constructed out of two William IV farthings. The Germans love to write on their brooches “God punish England.” The Englishman has placed on his “God forgive Germany.” There is the true spirit— one, moreover, perfectly compatible with the dealing of hard blows in action.

Comments