From ‘Array the Nation’, The Spectator, 22 May 1915

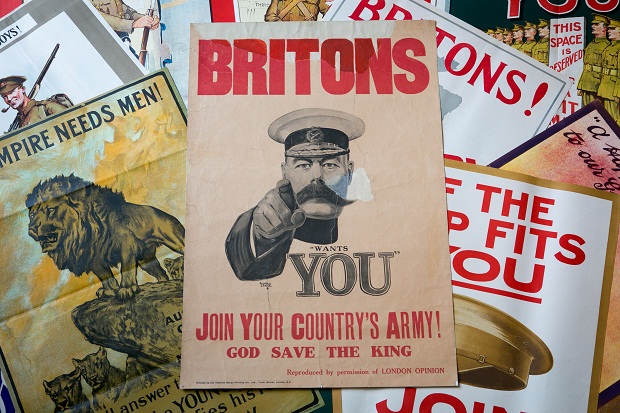

THERE have been many surprising things in this war, but perhaps the most surprising of all is Lord Kitchener’s speech in the Upper House on Tuesday afternoon. In it he told the nation that he wants three hundred thousand more recruits “to form new armies.”

If he had asked for a million, or even two million, more men we should not have been surprised, though even then, taking the Army and Navy together, we should not be doing, per head of population; more than, or even as much as, the French; and should be doing a very great deal leas than the Germans.

At such a juncture as this to ask for only three hundred thousand men literally makes one’s brain reel. It would seem to shows one of two things: either Lord Kitchener during the ten months that have elapsed since the beginning of the war has obtained far more men than the nation has any idea of, or else—which of course is a perfectly incredible, ridiculous, and impossible supposition— Lord Kitchener is not aware of the wastage of war, and is under the delusion that the cadres of his fighting force can be kept up to strength (the absolutely essential condition for an efficient army) without a huge reserve. A very little consideration will show that the notion of such a miscalculation on the part of so great a soldier as Lord Kitchener must be dismissed.

We must not make any calculation as to the exact numbers of the men who are at this moment outside England fighting our enemies. Let us, assume, however, purely for the sake of argument, that, taking into consideration not only the Army in Flanders, but our forces at the Dardanelles, on the Persian Gulf, and in other parts of the world, we shall soon have a million men in the field. But when our men are fighting as they are bound to fight this summer, for the summer is the soldier’s season, if we average the war wastage of the great battle months, such as May has proved, with that of the quiet months, it will at the very least be ten per cent per month. [It may of course prove to be much more.] This means an immediate wastage of one hundred thousand a month to be made good. It means that unless one hundred thousand fresh men are raised every month, the armies in the field will begin to wither away. Of course up till now there has been no such wastage. We are speaking of the future—of the period when the New Army will be at the front.

If no new men are raised, an Army of a million would in ten months cease to exist. Therefore Lord Kitchener’s new army of three hundred thousand, if he got them by June 1st, would have disappeared by September 1st. No doubt Lord Kitchener has other great supplies of men for drafting purposes, and could keep a million men in the field for a year without using these extra three hundred thousand. In all probability, however, we shall ultimately want to have, not one million men, but a million and a half in the field and a million and a half at home to feed them.

What, then, is the explanation of this demand for a handful instead of the great bunch which is required? We can only suggest that Lord Kitchener has unhappily rejected the idea of adopting the principles of scientific recruiting or of seriously arraying the nation for war, and has determined to content himself with continuing, or even exaggerating, that haphazard system of dipping his bucket into the human pools when and where he can, instead of first collecting all the water into one big pool and then systematically draining it off into the Army buckets. He has only asked for three hundred thousand men now, but he means directly he has got them to ask for another three hundred thousand, and so on, and so on. If that is so, the man who has made so, few mistakes in his military career is at last making a great error, and we should be guilty of a grievous crime if, because of our respect and admiration for Lord Kitchener—which since the war, we may say, has become unbounded—we were to refrain from pointing it out, and imploring him and the Government to give up this foolish plan of little packets and to array the nation for the provision both of men and of shells and other munitions of war.

We venture to prophesy that what is going to happen is this. Some three months hence, or it may be even earlier, it will be found that there is an imperative need for supplying drafts to our armies at the front, and that the voluntary system is proving inadequate to supply them. Then the Government, in a panic of haste, will decree compulsion. The result will be that compulsion will be applied higgledy-piggledy and anyhow.

To begin with, we shall not know exactly to whom to apply it. This will mean that some districts will be asked for too many men and some for too few, and men will be got anyhow and anywhere by a system which will in effect be that of the press-gang—an odious, tyrannical, and detestable form of raising men. And remember that a hasty, muddled system of conscription is certain to fall much more heavily upon the working class than upon the richer class, whereas a properly arranged system of scientific recruiting through the means of a preliminary military census can be made to be accurately just and impartial to all classes.

Therefore, once again we ask that the nation shall be arrayed both for the factory and for the field, and that we shall at once, and in spite of official and military optimism, count up what men we have got of military age and how we can best use them. And here we would say that we think that the definition of military age should be expanded. It is now nineteen to forty. We would make it from seventeen to forty. That, however, is a matter of detail and not an essential. Only by arraying the nation for the war can we meet the needs of the hour adequately and justly. If we were the Government, the necessary orders would issue to-morrow. We have the machinery of the census ready. Why not apply it?

Comments