Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë, reviewed 18 December 1847

An attempt to give novelty and interest to fiction, by resorting to those singular ‘characters’ that used to exist everywhere… the incidents and persons are too coarse and disagreeable to be attractive, the very best being improbable, with a moral taint about them, and the villainy not leading to results sufficient to justify the elaborate pains taken in depicting it.

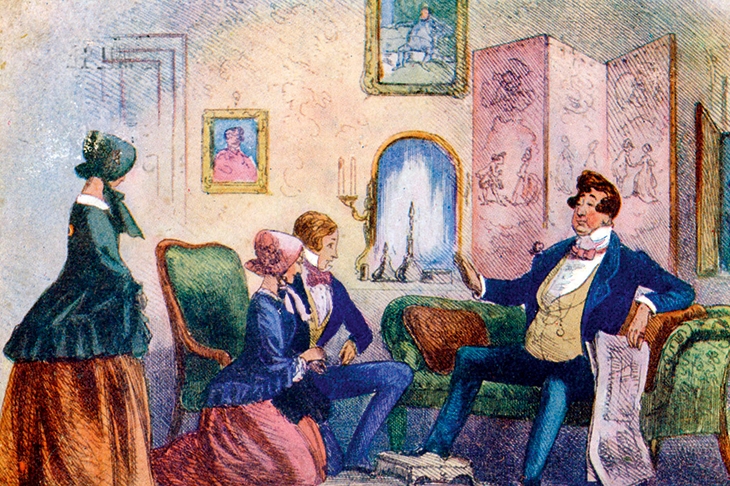

Bleak House by Charles Dickens, reviewed 24 September 1853

Bleak House is chargeable with not simply faults, but absolute want of construction. A novelist may invent an extravagant or an uninteresting plot — may fail to balance his masses, to distribute his light and shade — may prevent his story from marching, by episode and discursion: but Mr Dickens discards plot, while he persists in adopting a form for his thoughts to which plot is essential, and where the absence of a coherent story is fatal to continuous interest. In Bleak House, the series of incidents which form the outward life of the actors and talkers has no close and necessary connexion; nor have they that higher interest that attaches to circumstances which powerfully aid in modifying and developing the original elements of human character.

A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen, reviewed 22 June 1889

Ibsen’s play, about which everyone is talking, is a rather high-flown attempt to make men realise how grave a wrong it is to women to treat them as if they were mere toys made for men’s pleasure, rather than for companionship in study, duty, and responsibility. That is no doubt a very wholesome and necessary lesson; but the Norwegian dramatist, whose play is by no means remarkable for either intellectual or dramatic force, has urged it in a spirit and applied it in a form which is more likely to bring it into discredit than to make sober converts to his teaching.

The Moonstone byWilkie Collins, reviewed 25 July 1868

The Moonstone is not worthy of Mr. Wilkie Collins’s reputation as a novelist. We are no especial admirers of the department of art to which he has devoted himself, any more than we are of double acrostics, or anagrams, or any of the many kinds of puzzle on which it pleases some minds to exercise their ingenuity. Still if readers like a book containing little besides a plot, and that plot constructed solely to set them guessing, there is no particular reason why they should not be gratified… In the Moonstone, however, we have no person who can in any way be described as a character, no one who interests us, no one who is human enough to excite even a faint emotion of dull curiosity as to his or her fate. The heroine is an impulsive girl, generally slanging somebody, whose single specialty seems to be that, believing her lover had stolen her diamond, she hates him and loves him both at once, but neither taxes him with the offence nor pardons him for committing it, a heroine who seems to have been borrowed from one of those old novels where everybody is miserable because nobody will talk common sense for five minutes. The hero has no qualities at all.

Desperate Remedies by Thomas Hardy, reviewed 22 April 1871

There are things which men do voluntarily, against their own better judgment, but for which they have, at least, this excuse, that it is expected of them, and non-fulfilment of this expectation would lead to difficulty and complication; as when a clergyman professes belief in all that the Church teaches, and when a Chancellor of the Exchequer removes a tax which the people have decided is obnoxious. But we never heard of the man who got himself into difficulties by refusing to write a novel which no one but himself has had any thought of his writing. So that it seems to follows that our unknown author thinks either that his story is justifiable; or that he cannot do a better description of work, and must do something… Here are no fine characters, no original ones to extend one’s knowledge of human nature, no display of passion except of the brute kind, no pictures of Christian virtue, unless the perfections of a stock-heroine are such; even the intricacies of the plot show no transcendent talent for arrangement of complicated, apparently irreconcilable, but really nicely-fitting facts… If we dwell on the one or two redeeming features, and step in silence over the corrupt body of the tale, it is because, should our notice come under the eye of the author, we hope to spur him to better things in the future than these “desperate remedies” which he has adopted for ennui or an emaciated purse. … But we have said enough to warn our readers against this book, and, we hope, to urge the author to write far better ones.

The Tragic Muse by Henry James, reviewed 27 September 1890

When any person acquires a taste for an article of diet which is not attractive to the unsophisticated palate—say, caviare or truffles—he will notice, should he be in the habit of examining his sensations, that his pleasure is derived from the very quality of flavour which in the first instance moat strongly repelled him. In this respect, there is an exact correspondence between taste dietetic and taste artistic or literary. For example, there is probably no known instance of the “natural mind” having been drawn by instinctive admiration to the pictures of Mr. Whistler or the books of Mr. Henry James; for to the natural mind the former are meaningless, and the latter dull… This being so, it seems highly probable that the little company of superior persons who regard the novels of Mr. Henry James as specially admirable and enjoyable works of art, will attach a peculiar value to his latest book, The Tragic Muse, which is, we think, stronger than any of its predecessors in those Jamesian peculiarities by which they are charmed and the profane crowd repelled. Though the book is a very long one, there is even lees of that vulgar element known as “the story” than usual; indeed, were the narrative summarised, it would be seen that Mr. James has all but realised that noble but perhaps unattainable ideal,—a novel without any story at all. Even that surely less vulgar kind of interest which is secured by the lively and lifelike presentation of character, is minimised to the utmost, for Mr. James cannot be said to present his men and women at all: what he does present is a thin solution of talk, in which they are, so to speak, dissolved, and from which we have to extract them by a mental process of precipitation. Considering that the flow of talk is perpetual, and that all the people in the book are fond of talking about themselves, it is absolutely astonishing how much Mr. James manages to write without giving a single revealing hint.

The Colour of Memory by Geoff Dyer, reviewed 2 September 1989

Geoff Dyer’s first novel, The Colour of Memory (Cape, £11.95, pp.228), has inspired me to leave the country. It is a plotless novel, not so much written as observed, where youngish people on the dole in Brixton with midly precious names like Foomie and Steranko sit on roofs, drink beer, go to parties, name-drop a lot and smoke loads of grass. It is a pleasant existence, based more on the continuous capitulation to desire rather than an the life of the mind, at times poignantly evoked. There is a great deal of the elegy in Dyer’s book: he describes everyone with all Heathcote Williams’ tenderness for the whale, but with a little less irony or detachment. To tell the truth, his relentless humanism can get a bit much. Driving a bus, for example, is ‘an affirmation of human potential of the same order as that glimpsed in a work of art or in the performance of any kind of sport, or in the playing of a musical instrument.’ That is about the level the book operates on, managing to be both self-obsessed and deluded at the same time. Mental impoverishment is rather like vanity and humility, in that the more one has of each the less on thinks one actually has, and Dyer thinks he is awfully clever indeed… As someone once said of Kerouac, this isn’t writing, but typing, and it would not be worth mentioning if it was an uncommon problem. But it is a common problem, especially in this country.

Comments