Charlie Taylor is not so much the canary in the coal mine of prison conditions as the British Gas engineer nailing a ‘condemned’ sign to the entrance while ministers skip gaily into the fumes. Taylor, just reappointed to a second three-year term as HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, has been raising the alarm about our crumbling prisons estate since taking up the role in 2020. He also writes on prisons every now and then for The Spectator, so you know he’s a good egg.

The response from ministers has amounted to little more than boilerplate but Taylor’s latest intervention ought to jolt them out of their complacency. He tells the Guardian that one in ten prisons in England and Wales ‘struggle to be fit for purpose’ and ought to be closed down. He cites HMP Pentonville, designed to house 450 inmates but currently cramming in 1,200, and HMP Wandsworth, a 1,000-capacity prison with 1,600 prisoners. Over-capacity and under-staffed Wandsworth was in the news recently when 21-year-old former soldier Daniel Khalife allegedly escaped while on remand. (Khalife has been charged with offences, which he denies, under the Terrorism Act and the Official Secrets Act.)

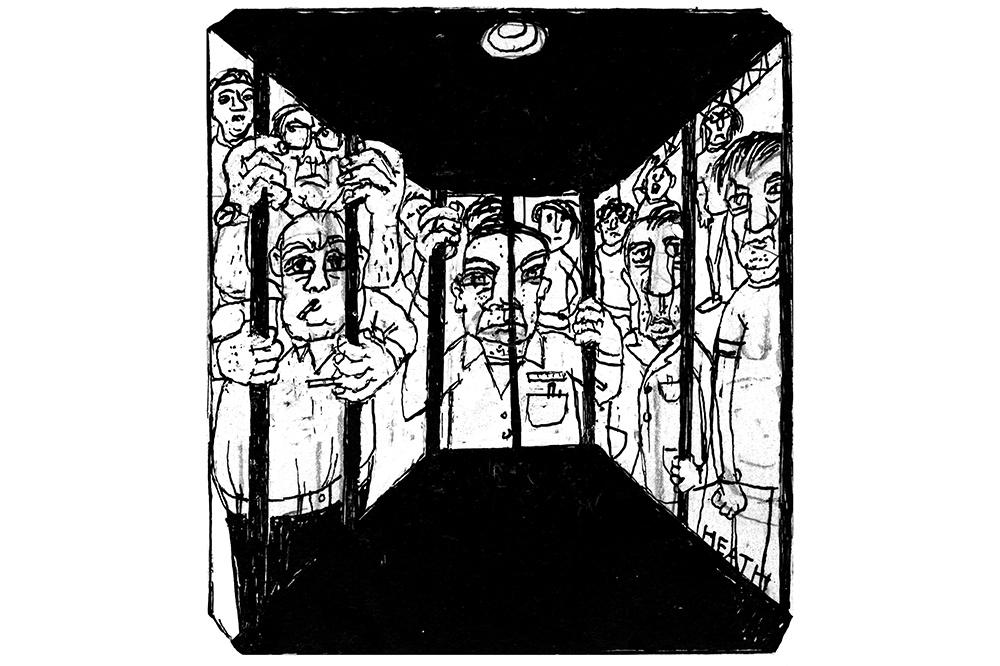

Following the Khalife incident, Taylor said Wandsworth ‘really needs closing’. In their most recent report, his inspectors found the jail to be ‘squalid’, rat-infested, strewn with rubbish, failing to meet infection control standards, and using bedsheets to counter the spread of bird faeces. Taylor himself observed a cell being prepared to house a new prisoner despite the fact it had just been burned out. He describes the state of the cell as ‘hideous’ and says it should have been taken out of commission and repaired before placing anyone in it.

Wandsworth is an egregious case but not entirely an outlier. In May, inspectors noted high levels of prisoner deaths at HMP Lowdham Grange (category B, Nottingham), an institution which displayed a ‘poor state of governance’, ‘a failure to investigate consistently allegations of misconduct among staff’, and ‘high levels of self-harm’ by prisoners. In April, they recorded ‘extremely concerning’ and ‘deeply troubling’ conditions in HMYOI Cookham Wood (young offenders, Kent), where children are held in ‘dirty’ cells, some segregated for more than 100 days at a time, amid a ‘near total breakdown in behaviour management’.

Also in April, inspectors found parts of HMP Risley (category C, Cheshire) to be ‘beyond repair’, including showers in ‘appalling condition’. In January, they documented ‘dramatic increases in violence’ at HMP Feltham B (young offenders, London), with prison officers sustaining ‘serious injuries’ breaking up ‘planned assaults between groups of prisoners’. Nor is this limited to the men’s estate. Earlier this year, I wrote about HMP Eastwood Park, a women’s prison in Gloucestershire where inspectors documented blood-spattered cells and inmates reduced to sharing underwear.

Raising the dangerous and inhumane conditions in our prisons typically brings a shrug of indifference, if not angry reproach about how these awful people are getting what they deserve for breaking the law. That’s a view many would share but it does come with consequences. One such consequence is other countries refusing to extradite people accused of serious offences.

Earlier this year, a court in Germany rejected an Interpol red notice, also known as an international arrest warrant, from Westminster Magistrates’ Court seeking the transfer of a man wanted on charges of drug-trafficking and money-laundering. Karlsruhe Higher Regional Court refused to extradite, citing in its reasoning ‘the state of the British prison system’, and the suspect was subsequently released by German authorities. The Guardian reported at the time that the man’s lawyer, who had authored a thesis on conditions in UK prisons, presented evidence to the court showing overcrowding, understaffing and violence in British jails.

This marked the first time a German court had taken such an action, but the situation is not unique. In June, an Irish High Court judge refused a request from the Crown Office to extradite to Glasgow a man wanted on suspicion of a serious assault and an alleged offence under the Firearms Act. Mr Justice Paul McDermott ruled that Ireland could not hand the man over because the conditions inside Scottish prisons posed a ‘real and substantial risk of inhuman or degrading treatment’. This is despite Scotland making strides towards a more progressive criminal justice system.

Sooner or later, something is going to go boom

There are, of course, other reasons to reform our prisons. We should want conditions in custody to be safe, humane, productive and rehabilitative as a matter of moral principle. We should recognise that incarcerating offenders in violent and unsanitary jails where cell time is maximal and work or education minimal is not going to reform their conduct. In hardening criminals and failing to prepare them for life on the outside, all we achieve is more crime and more time inside. Retribution is a legitimate aim in penology but a dead end unless supplemented by rehabilitation and effective reintegration.

When challenged on overcrowding and conditions, ministers point to forthcoming additional prison places, but that’s just sticking a bit of duct tape on the aforementioned gas leak. Sooner or later, something is going to go boom. We need to upgrade facilities, not least in provision of mental health services, but the reform required is more fundamental. We need to rethink the aims of the criminal justice system and the most effective means of achieving them. Part of that rethink should involve confronting our over-reliance on prison, whether that’s the prevalence of short sentences or the potential for prison to help habituate rather than deter criminal behaviour.

Those are big and complex and provocative questions and ministers are plainly not ready to consider them. But they ought to heed the warnings from Charlie Taylor. They had enough confidence in the man to renew his appointment. They should have enough respect for his work to act on its findings.

Comments