John le Carré, the master of British spy stories, may have died last December, aged 89. But the dastardly world of double agents he relished in exposing lives on.

A British man has been arrested in Germany on suspicion of spying for Russia. German federal prosecutors allege that the man — named only as ‘David S’ and said to work at the British Embassy in Berlin — passed documents to Russian intelligence ‘at least once’ in return for an ‘unknown amount’ of money.

Berlin was the epicentre of le Carré’s world of espionage. He served as a spy in Germany himself and his breakout hit, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, is set in Berlin. His novel is also about that figure beloved of thriller-writers and the reading public — the double agent, as this figure at the British Embassy in Berlin is alleged to be.

The British in particular have a strange approach to double agents. Even the name ‘double agent’ has a sort of glamour to it; much more glamour than, say, the word ‘traitor’, which is what double agents necessarily are.

The truth of it is that the spying life is really rather dull — more Brooke Bond than James Bond.

It’s largely the fault of the Cambridge spies. They were traitors, every one of them. But they were clever, sophisticated, upper-middle-class traitors. Kim Philby went to Westminster School and Trinity, Cambridge. Guy Burgess went to Eton and Trinity, too. Donald Maclean was at Gresham’s before joining his comrades at Cambridge. And Anthony Blunt went to Marlborough and Trinity.

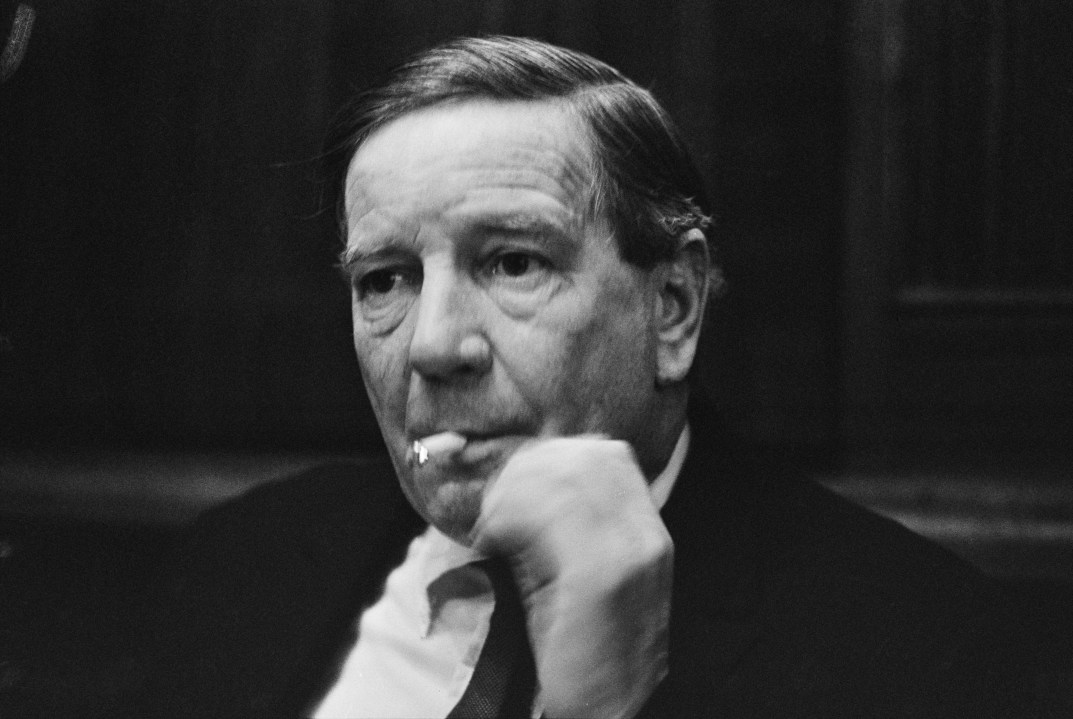

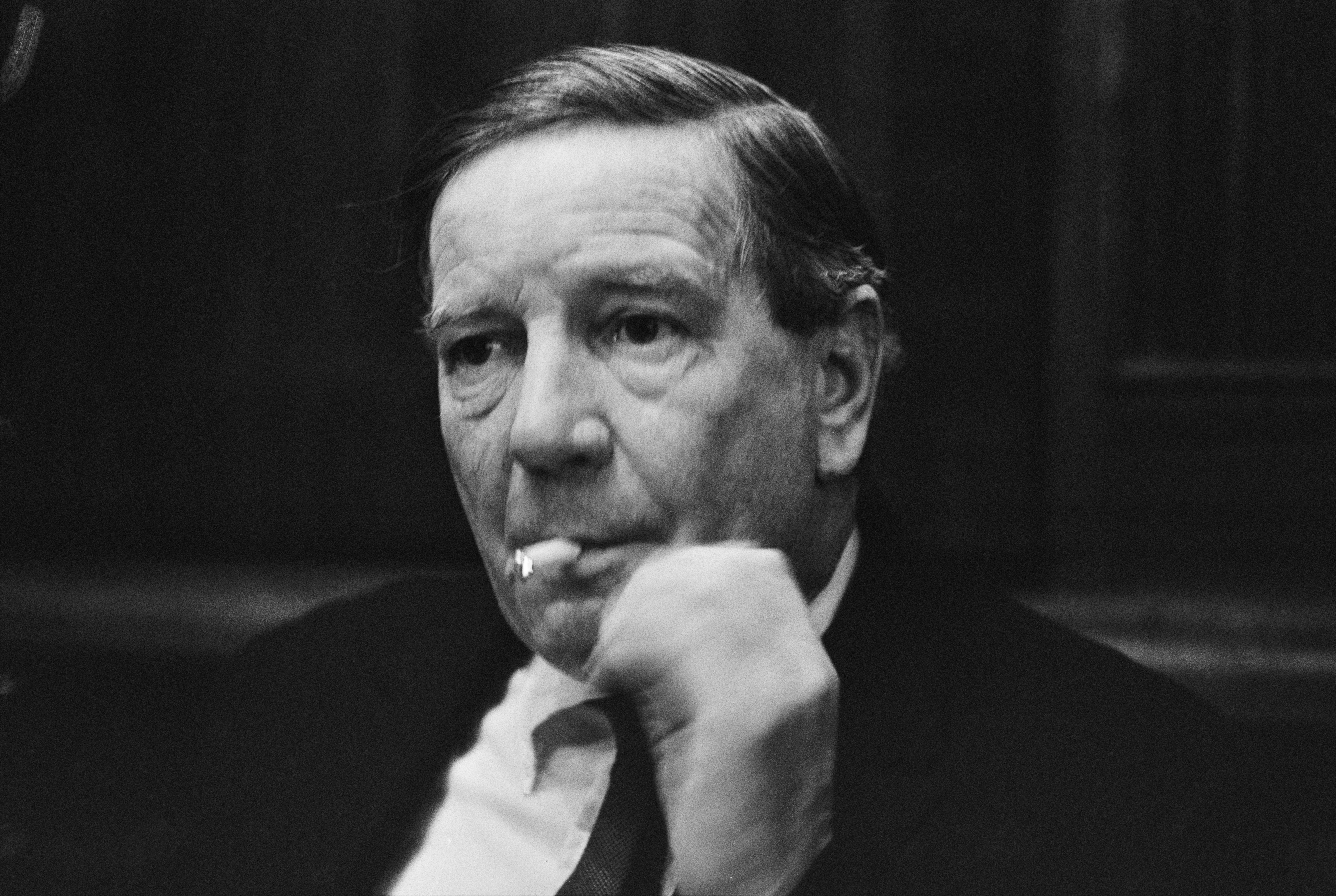

Margaret Thatcher said the MPs who brought her down were guilty of ‘treachery with a smile on its face’. Well, the Cambridge spies were guilty of treachery with big brains, wit and the right kind of suit. Just look at Kim Philby’s press conference in 1955 when he denied being the third man involved in the defection of Burgess and Maclean. He’s so languid, eloquent, smiling and diffident. Who could fail to be charmed by him — or fail to believe the wicked old liar?

Even when the Cambridge spies were exposed, they were indulged. Anthony Blunt’s treachery was discovered in 1963 and he confessed in 1964. The Queen was told — and yet he remained Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures until 1973. His evil wasn’t exposed to the public until 1979.

Part of that cover-up was due to the authorities’ fear of embarrassment after the terrible shame of Burgess, Maclean and Philby. Part of it, too, was the supposedly complex nature of British communists. Before the war, there was a fashionable, non-traitorous aspect to communism that attracted the Cambridge spies to the cause. After the war, those affiliations and the attachment to Russia meant they were traitors because Russia had become the enemy during the Cold War.

Still, today, extraordinarily, some people find Soviet Russia a beacon of ideal political behaviour. They find it easy to forgive Stalin’s murder of millions of Russians — somehow supposedly less wicked than Hitler’s mass murder. The wickedness of the double agent is further blurred by dozens of books and films which invest them with a sort of attraction.

Take Alan Bennett’s plays, An Englishman Abroad (about Burgess in Moscow) and A Question of Attribution (about Blunt’s relationship with the Queen). They are a joy — and a gift for a writer like Bennett, who loves playing with all the comic effects that arise from double meanings: irony, sarcasm, overstatement and understatement. Double agents are full of double meanings.

British audiences love these comic effects, too. For a country of people that never mean what they say and never say what they mean, double agents exert a powerful attraction. If spies are like us, we like them. We cast them as eccentrics rather than traitors. And we particularly like it if they’re a bit superior about our staunch allies, the Americans.

The truth of it is that the spying life is really rather dull — more Brooke Bond than James Bond.

When I interviewed Auberon Waugh in 1991, I asked him about the two occasions he tried to become a spy in the 1960s. ‘It can be very boring; stuck behind a desk. Even if you make it, with your cover you won’t appear successful to the outside world, being a very humble first secretary to an embassy at best.’

The same applies to being a double agent — there’s just an extra risk of being arrested to slap on top of all the boredom.

Comments