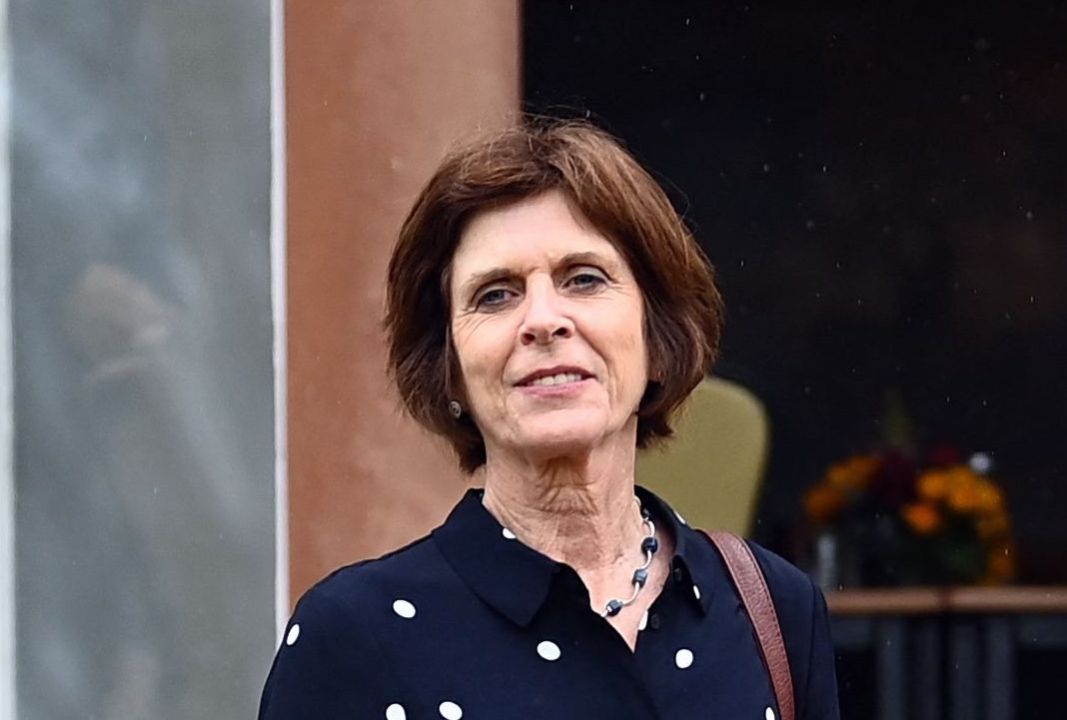

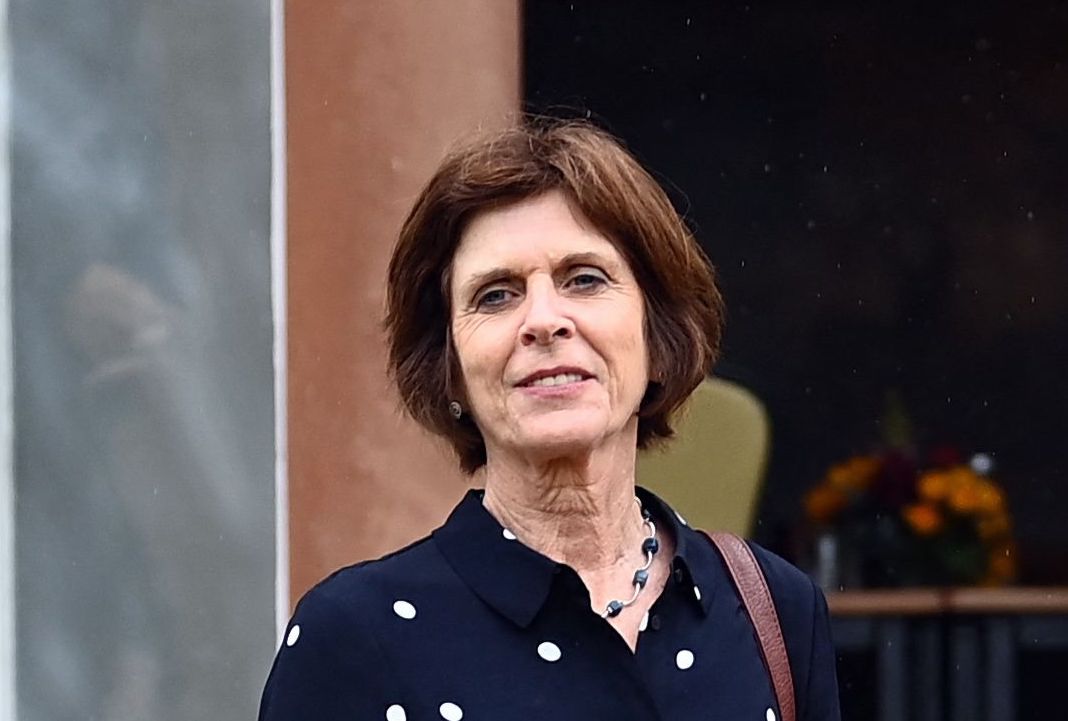

To enormous fanfare last week, the Dame Louise Richardson Chair of Global Security was established at the Blavatnik Business School in honour of the soon-departing Vice Chancellor. It was a remarkable event in a couple of respects – first, global security is frankly a dud subject for a chair at Oxford. More to the point, the Dame was appointed to this vanity project when she was still in office, which was an extraordinary departure from usual custom and protocol. Normally an honour of this sort would be proposed after the departure of the scholar it’s named after – normally an individual of exceptional distinction in an established field – and left to their successors to promote. In this case, she obtained it while she was actually in office.

The Chancellor, Lord Patten, who was instrumental in getting her appointed, did his best to justify the chair at its launch: ‘Before [Dame Louise] was a distinguished Vice Chancellor, she was a great teacher and a great scholar; through her work and her scholarship around terrorism and global security, she provided an extraordinary contribution to public policy.’

Except, she wasn’t and she didn’t. Her chief contribution to the literature on this subject was a book called What Terrorists Want, which has vanishingly slim claims to scholarship; supplemented by a chapter in a book she edited on the roots of terrorism published in 2006 plus a publication co-edited by Robert Art for the US Institute of Peace, a federal institute with no academic standing. Plus a book on Anglo-American relations during the Suez crisis. This, to be frank, doesn’t amount to great scholarship. The chair is based at the Blavatnik School of Government, itself something of a vanity project, semi-detached from the main objectives of the university itself. The Dame declared that she was ‘deeply touched that a number of generous donors came forward to create this chair in recognition of my time as Vice Chancellor.’

Given the diminishing autonomy of the individual colleges at Oxford during her tenure, and the increasing influence and funding of the central university administration – plus, it should be said, the apparent attempts to suppress the Oxford Magazine on her watch, the only publication in the university capable of expressing independent views on these things (an attempt which sits oddly with Dame L’s parting observations about being in favour of free speech) – that money could have been better spent. She also seems to have done her bit to try to kill off the independence of the university’s parliament (or sovereign assembly) called Congregation. She tried to exclude it from preliminary investigative discussion of the new Reuben (formerly Parks) College on the site of the former Radcliffe Science Library, effectively seeking to reduce it to rubber stamp status, then suggested that Congregation was ‘fossilised’.

Dame Louise is off to become president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, one of the biggest grant foundations in the US, proof again that once you establish yourself on the merry-go-round of public and academic directorates, there’s no limit to your upward trajectory.

Comments