During the years between school and my first job on a newspaper I worked briefly in Paris in an antique shop in the septième, owned by an ancient White Russian who had fled Petrograd at the end of 1917. She was a charming old woman, impeccably turned out and with beautiful manners. She was prone to quote Pushkin, flirt with young men and burst into tears several times a day. She shed a few even when she fired me for the understandable reason that I failed to sell any stock and knew next to nothing about antiques.

She claimed to be Countess Sonya X (she has living relatives), though I discovered much later that she had in fact been a countess’s maid and had somehow managed to get out of revolutionary Russia with some jewels, which she sold to establish herself in a business. Nobody knows exactly how she acquired them, but I am sure it was with charm and a smile.

She was the stereotype of a White Russian émigré between the wars and would have fitted neatly into Helen Rappaport’s enjoyable book, with its gallery of chancers, dreamers and rogues. There are also great writers and artists, coquettes, gigolos, spies and superb business brains, all of whom made new lives as refugees from the nightmare of the Bolshevik takeover and civil war.

The book also helps us understand why there was a revolution in Russia – and glimpse a little of what is happening there now: wealth in the hands of an oligarch class; power held by a corrupt, out of touch autocrat in thrall to a semi-mystical ultra nationalism; the threat of violence everywhere; a war that may be unwinnable. It all sounds familiar.

Many of the players in this story never managed to escape their past even in the safety and relative comfort of Paris. That, as Rappaport skilfully shows, was their tragedy in exile. She is an acknowledged expert on the Russian aristocracy and has written entertainingly on the Romanovs, with whom she has much sympathy. She likes an archduke (and especially an archduchess) and appreciates the glint of medals on a tunic. But she is too honest a writer to ignore the ruling caste’s failures and weaknesses.

Most Romanovs in Russia were truly ghastly, prone to excess in everything – spending, sex, greed, violence, arrogance and anti-Semitism. In exile in Paris they were equally awful, though thankfully the stakes were lower. Rappaport describes their squabbles over who was the rightful heir to a non-existent and never-to-be-reclaimed Tsarist throne with understated humour.

But the most interesting parts of the book are about a different demographic. After Turkey, France was the country that took in the most White Russians, with Paris alone giving homes to 50,000 between 1920 and 1930. At first the refugees were welcomed with open arms, since the deaths of so many young Frenchmen in the first world war had left a shortage of farm labourers and industrial workers.

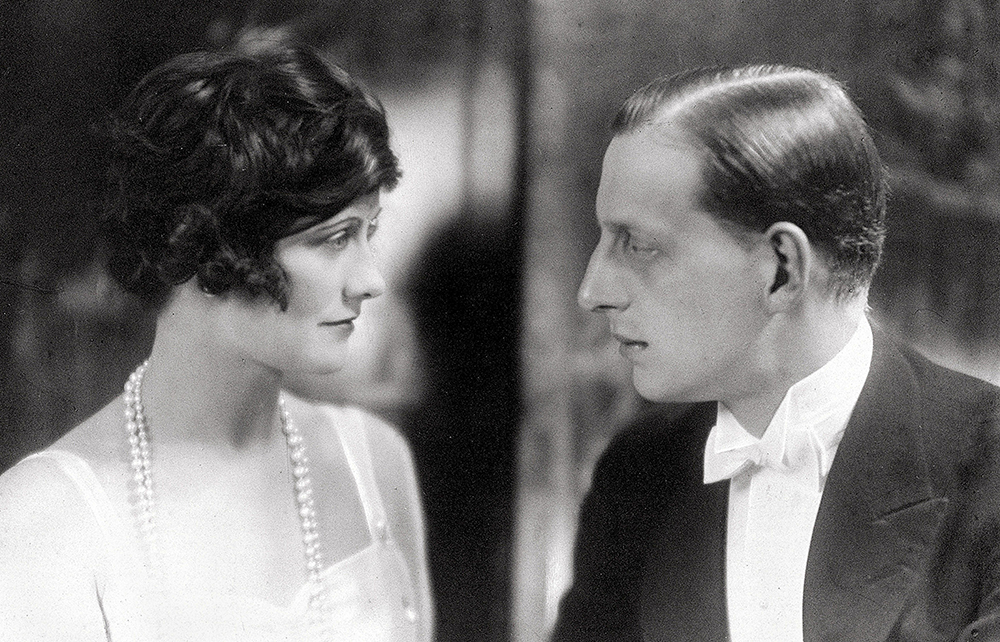

Many of the men found jobs at the Renault factory outside Paris, or as taxi drivers in the city (a union for Russian taxi drivers was formed and numbered 5,000 members). Women gravitated to the fashion trade, employed as seamstresses in companies established by Coco Chanel. (The creepy Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, a claimant to the Tsarist throne, was also paid by Chanel – but for his skills in the bedroom rather than with a sewing machine.)

The real pleasure of the book is the attention it gives to writers of the emigration. Nina Berberova and Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya, who wrote under the pen-name Teffi, are included, along with more famous authors such as Vladimir Nabokov, the Nobel laureate Ivan Bunin and the tragic poet Marina Tsvetaeva (who returned to Russia, where she perished in the Gulag). In one of her stories Teffi describes the existence of her fellow exiles in Paris:

We – les russes as they call us – live the strangest of lives here, nothing like other people’s. We stick together… not like planets, by mutual attraction, but by a force quite contrary to the laws of physics – mutual repulsion. Every lesrusse hates all the others – hates them just as fervently as the others hate him.

Rappaport provides plenty of entertaining details on this theme.

Comments