In the spring of 1994, year three of the Bosnian war, Ana, the daughter of the Bosnian Serb Lieutenant Colonel General Ratko Mladic, took a pistol from her father’s room in Belgrade – the special silver pistol with which he’d intended to celebrate the birth of his first grandchild – and shot herself in the head. She was 23 years old.

Ana Mladic hadn’t been herself, it was said, since returning from a study trip to Moscow where, people guessed, she had read in a newspaper about her father’s war crimes at Sarajevo. Or had been alerted to them by the cold-shouldering of fellow students. Her suicide was something Ratko Mladic – sentenced to life imprisonment in 2017 for genocide – could never come to terms with, telling himself she’d been murdered by the opposition. One of his last acts before being extradited to the Hague in 2011 was to go and lay flowers on her grave.

Croatian writer Slavenka Drakulić, in a chapter on Ana’s death in her book on Balkan war crimes and criminals They Would Never Hurt a Fly, speculated on what happened to Ana during those few days at Mladić’s house. It was, she said, the only time she ever felt compassion for the mass-murdering general. ‘Mladić finally experienced the pain that he had inflicted on thousands of people in Sarajevo, Srebrenica and Gorazde. But could it be the same pain? Can a butcher experience the same feelings as his victims? Yes, because the pain of a parent who has lost his child is a universal one.’

Both Ana and Daria, in their separate ways, have been collateral damage in their fathers’ careers

His life sentence, she concluded – the one he couldn’t escape – really began on that day. The chapter is entitled ‘Punished by the Gods’.

Now, in another Slavic war three decades later, Aleksandr Dugin, Muscovite seer, pro-war historian, and ‘Putin’s Philosopher’, has lost his daughter too – 29-year-old Daria Dugina, a journalist. The circumstances were very different but just as devastating. Having attended a cultural festival with Dugin on Saturday night, driving home alone in his 4×4, she was blown up by a car bomb. Possibly the bomb was meant for Dugin – ‘What doesn’t kill me kills another’ he tweeted, with unconscious prophecy, last year. It seems unlikely, despite the FSB’s shrill assurances, that the bomb was plated by ‘Ukrainian Nazi’ Natalya Vovk. As with Mladić, speculation changes very little about the event itself. Both Ana and Daria, in their separate ways, have been collateral damage in their fathers’ careers.

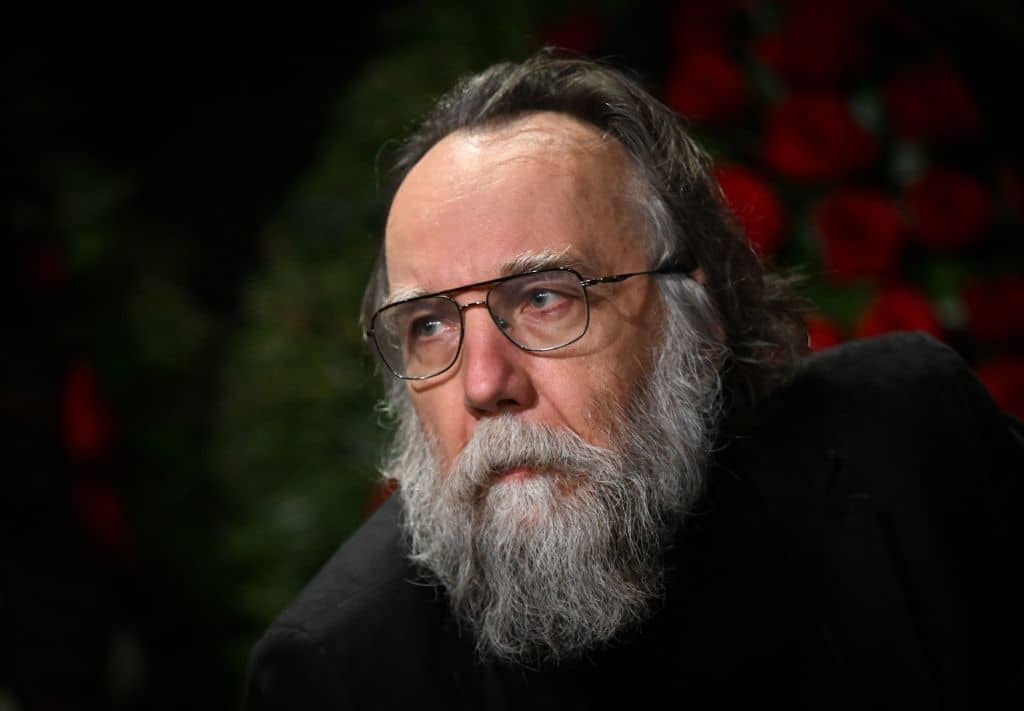

It is, however tragic, just the latest barely believable event in Dugin’s life – which has been full of them. Dissident rebel, guitar-playing fascist sympathiser, born-again Soviet diehard, polemical journalist, sociology professor, geopolitical guru, stern patriarch, Orthodox Old Believer – no one can say Aleksandr Dugin hasn’t rung the changes in his 60 years of life.

Dugin is almost an archetype of the Putin era. Like the Kremlin, he seems to reach back to the 19th century even as he seeks to design the 21st. Resembling his late namesake Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Dugin is similarly severe and bearded, that same uneasy blend of nationalism and Orthodox Christianity, but without the sublime absolving works of fiction which Solzhenitsyn produced. Anyone wanting to understand the moral schizophrenia of the Putin years – the blend of brutality and queasy religiosity, the attempt to have it all ways to mobilise support, the regime’s grasping at a metaphysical basis for its geopolitical and internal crimes, could do worse than study this man – even photos of him. He seems, for all his colourful past, to have stepped out of an icon of St. Spyridon. It’s difficult to think of any other nation – apart, perhaps, from Mladić’s Serbia – producing a similar figure.

In his book Black Wind, White Snow, partly an account of Dugin’s career, writer Charles Clover – an acquaintance of his – doesn’t go easy on Dugin’s protean careerism and sinister mix of influences – Nazism, Bolshevism, numerology, the occult. Yet his subject also comes across as charismatic, generous with his time, and with a subtly discernible sense of the absurd. Dugin, whatever his doctrines, is interesting to observe and never dull to read about. Yet he was little known, outside the circle of Russia junkies, until last week – even Russian friends often didn’t know who he was. What has put him on the map – and led to a spate of ‘Who is Dugin?’ pieces in the international press – has undoubtedly been his daughter’s untimely death on Saturday night.

Most articles since then have given you a kind of ‘Dugin’s greatest hits’ packaged up for a prurient thrill. We get his ultra-nationalist past and his Kremlin influence as a geopolitical thinker. We see Dugin’s messianic, perhaps self-seeking Putinism – ‘Putin is everywhere, Putin is everything, Putin is absolute, Putin is irreplaceable’ – and the remark for which he’s most infamous, from 2014: ‘Ukraine has to be either vanished from the Earth and rebuilt from scratch or people need to get it… I think kill, kill and kill. No more talk any more. It’s my opinion as a professor.’

It was this comment which led to him losing his post at Moscow State University. It was clearly going too far. Yet his daughter Daria, strikingly similar in looks to her father, and described by Putin on Monday as ‘kind, loving, sympathetic and open… a Russian patriot’, appeared to have felt no such restraints either. The Azov regiment, she said in an interview, were ‘unpeople… not human any more, their ideology is death’; the ‘collective West’ were a ‘liberal Nazi civilisation’. Putin was right to put down the anti-war protests: ‘When your country is at war, there must be absolute unity… There is a decision, there is an act of will, and it must be executed.’ In all these statements you don’t know whether she’s speaking sincerely or trying – a little too hard – to please her father.

None of this is a reason for anyone to kill Dugina, or to crow over her death. Children are often dominated or in thrall to their parents and grow away from them. People can change their minds or reinvent and redeem themselves, choices sadly no longer open to Daria Dugina.

By all means hate an unjust man, Solzhenitsyn, Dugin’s spiritual ancestor, wrote. ‘But once he is overthrown, once the first furrow of self-awareness runs over his face as he crashes to the ground – lay down your stones! He is returning to humanity unaided.’

Fine words, but is Solzhenitsyn right? Far from being chastened by his daughter’s death, Mladić moved onto Srebrenica where, a year afterwards, he oversaw the execution of more than 7,000 Bosnian Muslims in one day. Dugin, in his otherwise dignified statement about Daria’s death on Telegram yesterday, was only too swift to blame the ‘Ukrainian Nazi government’ for it and call for renewed war efforts. Old men with beards, we see, however sternly they stare, however much they have read or enthralled us with their wisdom, can be just as flawed and fallible as the rest of us. As their daughters often realise too late.

Comments