I’ve never been a big fan of the Supreme Court, seeing it as a Blairite invention and – given our position in the European Union – a misnomer. But its decision to back the High Court and remind Theresa May that only parliament can dissolve laws that parliament makes is welcome. It has issued a useful refresher on constitutional law to certain MPs who might, in the excitement of the Brexit vote, have forgotten it.

The 17.4 million who voted for Britain to leave the European Union were giving advice, rather than an instruction, to Parliament. This ought not to be a controversial point. As the judgment said, David Cameron chose to hold a consultative referendum, rather than a legally-binding one (as the AV referendum had been). And why wasn’t the EU referendum legally binding? For the same reason that the 2014 Scottish referendum wasn’t legally-binding: it would be unthinkable for parliament to ignore such “advice”, or stand athwart the result of that referendum. That’s not how we do things in Britain. The Irish may ask people to vote again if they give the wrong answer in an EU referendum; the French president may act in defiance of referendums there. But in Britain, there is – or should be – no serious prospect of politicians trying to subvert direct democracy.

Fraser Nelson discusses the ruling with Isabel Hardman and James Forsyth:

On devolution, the Supreme Court has also reminded Nicola Sturgeon that relations with the EU are a matter for the UK government. This was a unanimous verdict, unlike the overall verdict passed by eight votes to three. Theresa May has no duty to consult Holyrood.

The fault for this entirely unnecessary drama lies with those who advised Theresa May over Article 50 in the first place. The issue is fairly simple: if parliament passed a law signing Britain up to the EU then parliament needs to pass a law undoing it. As Vernon Bognador memorably put it, sovereignty can be expressed in just eight words: what the Queen in Parliament enacts is law. The only power that the EU ever had in Britain is power that parliament voted to give it. If that power is to be retrieved, then parliament must vote to reclaim it – following the result of the 23 June referendum. No judge, no Eurocrat and no Prime Minister can undo what Parliament has done. All of this was explained by the rather magnificent High Court judgment – which, unsurprisingly, the Supreme Court has just reinforced.

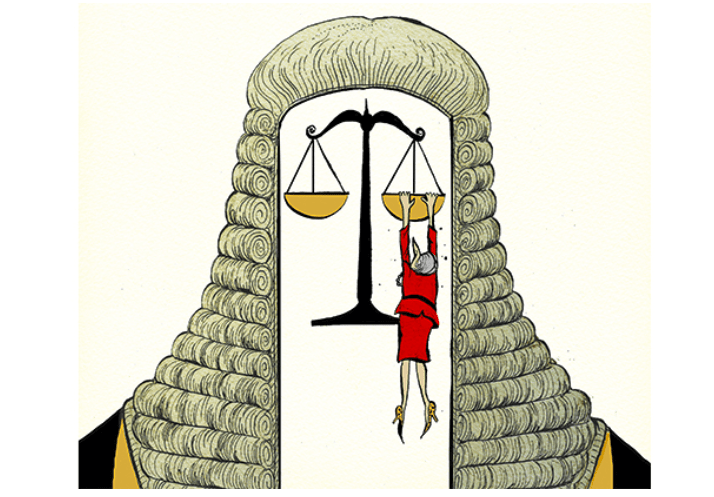

Given that an Act of Parliament took us into the EU, no one – not a judge, not a Eurocrat and not a Prime Minister – can take us out. It “can only lawfully be carried out with the sanction of primary legislation enacted by the Queen in Parliament”. The law can be “very short indeed” but a law is needed, authorised by the crown – which is the sole source of legal authority. Bottom line: no law changes without Her Majesty’s (which, in our system, means parliamentary) consent. Nobody puts Lizzie in a corner.

The British constitution is unwritten, reflecting a British distaste for schematic articles of political faith. For centuries, we have got along rather well by following some basic rules – and an understanding that laws are decided not by 10 Downing Street or by judges but by the Queen, through Parliament. When the High Court pointed this out, saying that a parliamentary vote is needed to start proceedings to withdraw from the European Union, many Brexiteers rounded on the judges as if they were trying to somehow subvert the will of the people.

This is, and always has been, arrant nonsense. The Spectator is the only publication to have supported Brexit in both the 1975 and 2016 referendums, each time due to a belief that the British system of government is superior to the over-reaching institutions of Brussels, Luxembourg and Strasbourg. Our system works well precisely because we have a common law tradition and judges who can be depended upon to uphold the law – rather than buckle under periodic outbreaks of popular, financial or political pressure. And if No10 wants to change the law without consulting parliament, it is for judges to point out the unconstitutionality in such a dangerous suggestion.

As the late Tom Bingham observed, Britain’s acceptance of (and insistence upon) parliamentary sovereignty distinguishes us from most other countries – and all other members of the European Union. The Supreme Court has restated who calls the shots: not them, not No10 but parliament. And if this is inconvenient for the Prime Minister? Tough. It is not for judges to clean up a mess made in Westminster.

So “the people” are being defended, rather than defied, by the High Court’s decision. Yes, people elect governments and vote in referendums. But people are also protected by laws, interpreted by judges who are – mercifully – not influenced by the hissy fits of politicians or the media.

The Supreme Court’s decision will not derail Brexit – only politicians can do that. The judges have made life slightly harder for the government but there is not (yet) a law against that. Their judgment underlines a wider point: that the vote for Brexit was a vote to defend a British system where people live under their own laws, as defined or repealed by Parliament – and by no one, or nothing else. The behaviour of some of its justices, especially Lady Hale, has made this more controversial that it ought to have been. The Supreme Court ought to be seen as absolutely impartial, and some of its judges have fallen short of the standards they set for themselves and others. It reached the right decision, but has not covered itself in glory in the process.

Upshot: Theresa May needs to win a vote in parliament, which she should be able to do quite easily. Had she this so earlier on, rather than sought this spectacular and needless conflict with the judiciary, we’d all have been better off.

Comments