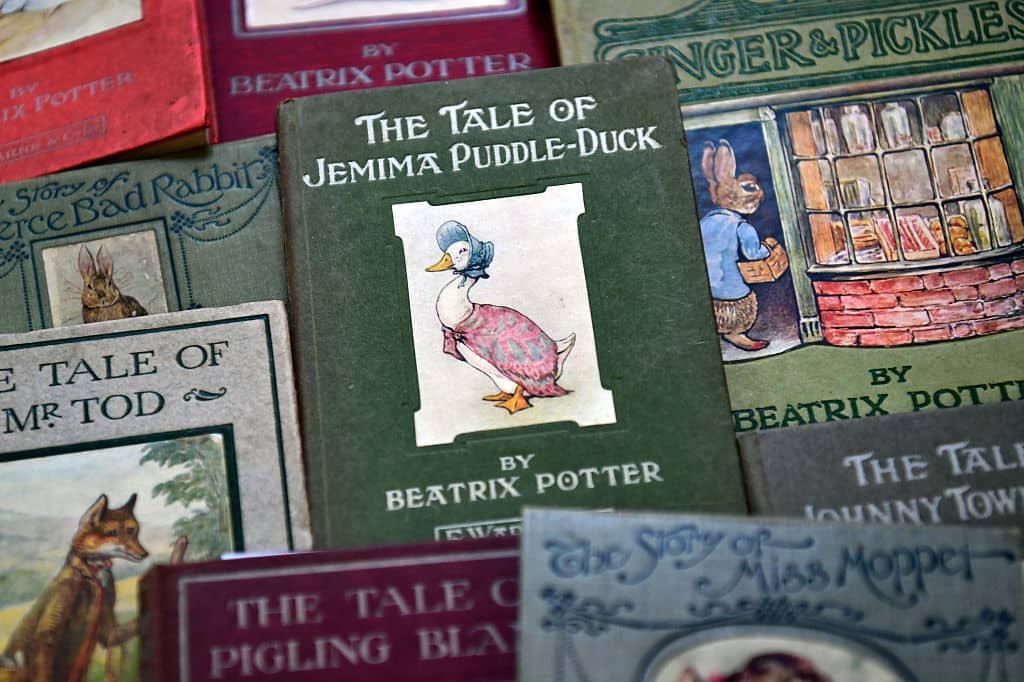

Mrs Tiggy-Winkle, Jemima Puddle Duck, Squirrel Nutkin and Timmy Tiptoes are names that take me back to my childhood. Every year, my mum would drive me and my four siblings to the Swiss mountains for family holidays. To avoid our moans of ‘are we there yet?’ she created voices for all of the Beatrix Potter characters and invented songs which we all sang along to. Although we knew the stories of Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and, of course, Peter Rabbit, it was later that I learnt about the fascinating woman behind the famous tales who is the subject of the V&A’s exhibition, Beatrix Potter: Dawn to Nature.

As the exhibition shows, Potter’s talents were multi-faceted: she was not just an author and illustrator but a natural scientist, anthropologist and award-winning farmer. We follow her life from her childhood in Victorian England to the beautiful landscapes of the Lake District which she later called home. It was here that she helped to protect thousands of acres with her conservation work. When she died in 1943, Beatrix left her land, including farms and buildings to the National Trust who have collaborated with the V&A to create this special show.

Potter was well ahead of her time

Potter channelled her intimate knowledge of the natural world into her illustrations. I think this is why her work captivates both young and old – we quickly recognise the cheeky look in the fox’s eye, the inquisitive nature of the rabbit and the kind way of the hedgehog. Her characters are never just fluffy and sweet, but often quite sinister with the villains being at the forefront of most of her tales; Mr Todd, the fox who dresses as a gentleman and makes Jemima Puddle-Duck believe he’s a trusting friend in order to roast her; Mr McGregor, the rabbit killer and the angry owl who rips squirrel Nutkin’s tail off. Her characters allow her to converge and compare the workings of the natural world with our human one: both are harsh spheres where there is no guarantee of survival.

Mrs Rabbit famously warns her bunnies about human cruelty. ‘Your father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs McGregor.’ I wonder if her darkly creative imagination was voicing her own experience of social hierarchy in British society. Potter was born into a typical middle-class Victorian home, where men went to their clubs and women were expected to remain uneducated. We see this in the character Samuel Whiskers, the large rat who snorts snuff whilst his wife waits on him. In an era when women’s voices went unheard, it seems that Potter was able to speak her opinions on cultural identity through her many stories.

She was seventeen when she first visited The Royal Academy where she saw a painting by Angelica Kauffman, a Swiss artist who became one of the only two female founding members of The Royal Academy. Kauffman produced androgynous figures in her work and saw past traditional attitudes towards womanhood. Potter – hardly perceived as an avant-garde artist – was nevertheless drawn to this rejection of tradition.

Potter was inspired by the idea that women could have careers in the arts. In a letter to one of her publishers, Norman Warne, Potter said, ‘It is pleasant to feel I could earn my own living.’ From there her independence grew. The exhibition portrays a woman whose achievements are found in both art and science. She was especially interested in mycology; the study of fungi and how certain mushrooms reproduce – she made over 350 detailed illustrations of fungi during her lifetime and wrote about her findings. Today, a mushroom boom is thriving across the food, fashion and wellness industries. Back then, however, the fungus attracted little attention – Potter was well ahead of her time.

Science was a particular passion of hers, but a field of work often closed to women in her own era. Only in the last few decades have her observations been recognised: the spores of Tremella depicted in some of her paintings were not formally identified by scientists until 45 years after she depicted them in her work. Despite never managing to have her scientific writing published (something she attempted to do at The Royal Society) she incorporated much of her skill for observation into her art and found different ways in which she could use her voice.

Potter didn’t allow herself to be confined by societal do’s and don’ts and found her own way to pursue a career. The Tale of Peter Rabbit was turned down by six publishers before being reconsidered by one of them. It became a best seller and has never been out of print. She later saw the business opportunity of building a brand and designed Peter Rabbit wallpaper, dolls and games.

This trail-blazing woman has become so much more than just a nostalgic reminder of my childhood. Her story made me think of those women who were unable to pursue a particular career path, those who were never permitted to reach their potential, and those who still feel that today. In my own life I have often felt undermined, treated like I was less capable and talked over. At times I have the courage to stand up against it, and other times I don’t. When met with rejection, Beatrix found other avenues where she could channel her interests and talent. She should inspire us all to live life on our own terms.

Comments