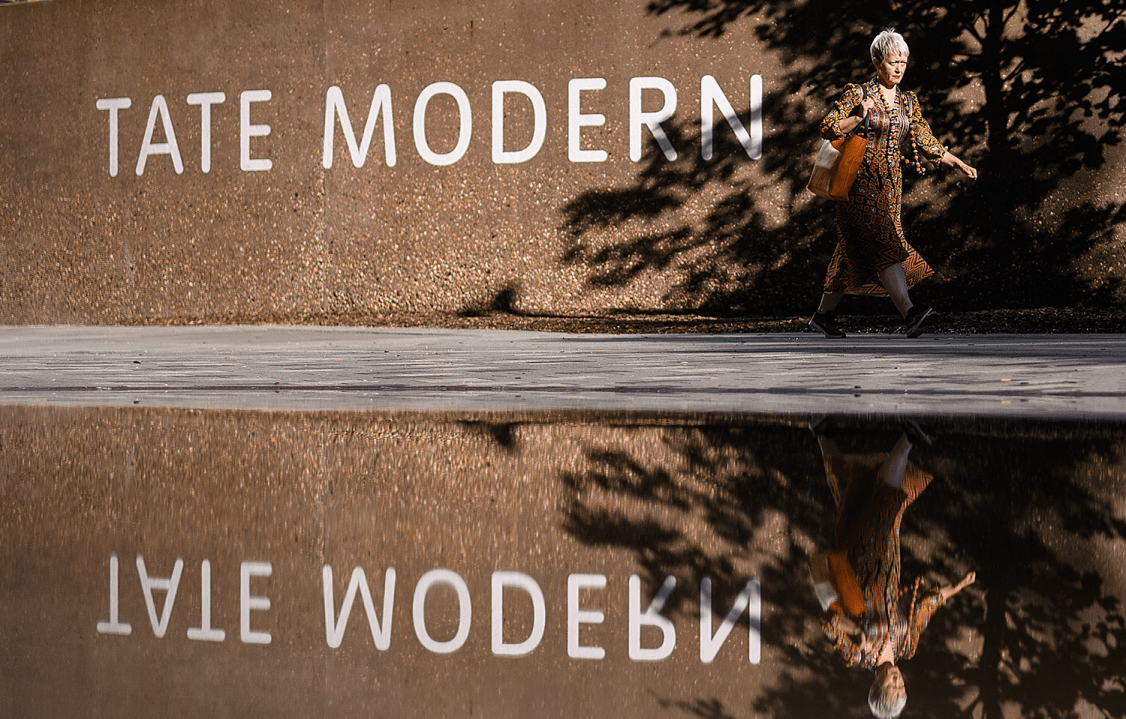

Twenty-five years ago today, the Tate Modern first opened its doors to the public. The main attraction: a nine metre-high steel sculpture of a female spider which towered over visitors to the Turbine Hall. In its first year, the Tate Modern saw twice its projected number of visitors. London’s first museum of modern art was an unmitigated success.

Say what you will about contemporary art, but it is undeniably true that the Tate Modern succeeded where others failed. While Manchester’s Municipal Gallery of Modern Art and Centre Georges Pompido struggled, the Tate Modern thrived. Riding the wave of Blairism, Britpop and pre-crash confidence, the thematically organised gallery, housed inside a derelict site on the banks of the Thames, attracted five million visitors in the millennium year – doubling the numbers of the Museums of Modern Art in New York and San Francisco combined.

As the Tate Modern marks its 25th anniversary, those running the gallery must ask themselves: what is it for?

Today, that story could not be more different. While the British and Natural History Museums have recovered after the pandemic, the Tate Modern has not. In 2024, a million fewer people entered the gallery once hailed a ‘cathedral for art’ than before the pandemic. The dire performances of their venues has forced the Tate Group to slash 7 per cent of its workforce to reduce costs – just five years after they offered 167 voluntary redundancies.

Have the public simply tired of art? It seems not. The National Gallery has seen visitor numbers grow by 14 per cent since 2022. But while they have undergone a rehang and rebuild, the Tate Modern has committed to the same increasingly tired tropes for a quarter of a century. Visitors are exhausted.

The Tate Modern’s avant-garde aspirations have driven it, sleepwalking, towards decline. Art that was once new and exciting has been replaced by the monotonous and constant banging of the social justice drum.

In celebration of Women’s History Month in 2022, the Tate Modern organised a screening of Marin Håskjoldand’s film What is a Woman? The 15-minute show platformed a heated debate between actors over the question of who should be permitted to enter a municipal swimming pool changing room. Whatever your answer to the question, is this really the sort of thing that will attract new and excited audiences? Is it even art at all?

The truth is the gallery has drifted as far as possible away from its radical intentions. Perhaps Toni Morrison is right that ‘all good art is political’, but at the Tate, only one kind of politics is allowed. Migration is always good; colonialism is always bad. The climate is always in a state of crisis; the West is always responsible. Gender will always be a construct; notions of the immutability of sex will always be condemned.

The winner of the Tate Modern’s prestigious Turbine Hall commission this year is Máret Ánne Sara. Her art seeks to preserve Sámi ancestral knowledge and values to protect the environment for future generations. Karin Hindsbo, the gallery’s director, waxes lyrical about her work, claiming that ‘by addressing the major social, ecological and political concerns of her community, Sara hopes not only to increase interest and awareness, but also to effect real change.’ Is this sort of agit-prop really the programming that will bring in audiences? The visitor numbers speak for themselves.

Curators now exist in a state of terror at the prospect of any criticism from their audiences. It took the gallery three years to pluck up the courage to display Philip Guston Now, due to concerns some of the artist’s work might offend. Guston’s work, much of which focuses on the Ku Klux Klan, offers a critique of racism, antisemitism and fascism. But at the Tate, where staff fear that visitors could be offended by even a negative depiction of white supremacy, a decision was taken to postpone ‘until a time we think that the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the centre of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted’.

Difficult topics are always avoided – in favour of projects like Embassy, ‘a space for activism and dialogue in support of Aboriginal land rights in Australia’, focusing on ‘challenges that Bankside communities are facing, particularly questions around gentrification, social justice, and community organising’. The Tate Modern has no faith in their visitors. In turn, visitors have lost all faith in the gallery, and they are voting with their feet.

As the Tate Modern marks its 25th anniversary, those running the gallery must ask themselves: what is it for? If curators cannot find it in themselves to put on the sort of art that attracts visitors, then why should they be allowed to continue, propped up by taxpayers’ money?

Comments