On Saturday night we sat around the kitchen table, my family and I, and had a takeaway from the Turkish restaurant on our high street. We opened box after box: chunky tzatziki; calamari in crisp batter; salty ovals of sucuk; flatbread studded with black and yellow sesame seeds; hot homemade falafels, crunchy outside and yielding within, smeared with cool hummus. And, which I’d been missing since lockdown began, lamb ribs: skin salty and crisp from the grill, the meat underneath sweet and chewy, tarring their bed of rice.

God it was bliss. But it made me feel melancholy, too. Meze & Shish only opened in the past couple of years — a well-appointed, tableclothy sort of local restaurant, well priced and serving first-rate grub. The sort of place that survives on neighbourhood word of mouth and relatively narrow margins. When I went in to collect my food I was the only customer. There were two staff, masked up, in the cavernous half-dark of the empty space. Will it survive this lockdown, I wondered. Will it survive the next?

Across the country, there will be local restaurants like this one — adapting to a sporadic takeaway business, making rent month by month on their empty square footages of floor space, finding new ways of hanging on. Who knows how many will make it by the time all this shakes out? Who knows what our high streets will look like? Our day-to-day lives? The lives of the people who bet their futures on these small businesses?

I’m not trying to make a point about the politics of this. You can wholeheartedly embrace lockdown as a necessary means of preserving the NHS and saving lives; or you can think that it is the greatest and most pointless imposition on the British citizen’s liberty in modern history. Both those positions, in different ways, will give you an invigorating rush, will give you the cheering sense that you’re a foot soldier in the battle against idiocy and ignorance. But neither will make a difference to the facts on the ground. Shops have been shut, aeroplanes grounded, offices emptied, and whole sectors of the economy are running on fumes.

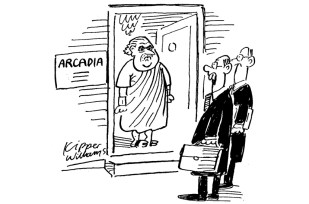

And we’re still, relatively speaking, near the beginning. Maybe not the beginnings of the virus — it’s possible, on a good day, to think we’re at least at the beginning of the end of that — but the beginnings of its effects on our world. Dishy Rishi is still in the gunwales, trousers rolled up to the knees, bailing away. But there’ll come a point when the magic money tree is at last leafless and looking stark against the winter sky. Restaurants, pubs, hotels, theatres, gig venues and all manner of shops will give up the ghost and be boarded up. Bigger businesses will retrench, at last laying off their furloughed staff. Zoom-weary white-collar workers will settle into the home office for the long haul, grateful still to have a job. The bustle of business districts will abate and the sandwich shops and coffee joints and after-work cocktail bars that serve them will reduce in number, prosperity and buzz. I’m talking here about a vibe rather than about politics — about the feel of our urban landscapes.

There’ll come a point when Rishi’s magic money tree is at last leafless and stark against the winter sky

Then, of course, there’s Brexit. I don’t mean to get into the politics of that either. We are where we are, and the die is nearly cast. It may make us feel better to keep relitigating the referendum or squawking against EU intransigence, railing against the bigotries of ‘gammons’ or the superciliousness of ‘remoaners’. But it’s happening to pro and anti alike. Perhaps, as true believers still hope, it will help to offset the Covid slump by unleashing Britain’s long-fettered animal spirits. Perhaps, as their opponents think, it will make things much worse. I hope it’s the former. I fear it’s the latter. But I’m not an economist and nor, probably, are you — and in any case what we hope or believe won’t make much difference.

Certainly, though, things will change. Even the most fervent partisans of Brexit tend to see it as a long-term good rather than an instant bonanza. We’ll have a period of what economists call creative destruction. How could we not? We’ll restructure, rebuild, grow the industries that will benefit from whatever our new arrangements are, and watch wither the ones that will not. This change will take years, and will alter the texture of our country. We’re embarked on a great slow movement to an uncertain destination, and it doesn’t help that we’re doing so on a plague ship.

I crested my twenties in the mid-1990s — which means that for most of my adult life the London I lived in was one of a dazzling aggregate prosperity that we took so much for granted we barely noticed it. Soho was bursting: a thousand toothsome meals from every world cuisine, a thousand drinks, a thousand adventures, within five minutes of everywhere. International money was pouring into the city and flowing through its streets as pleasure and possibility. Chancellor Gordon Brown declared an end to ‘boom and bust’ and many believed him. People jostled on the pavements, electrified by the warm hum of capitalism — or ‘late capitalism’ as we liked to call it, affecting disapproval as we enjoyed its fruits. The 2008 crisis put a dent in it, but not so deep that it didn’t spring back.

Now there’s the real prospect that decline will be a slow bleed and that recovery will be measured in decades rather than years. J.G. Ballard wrote in his memoir Miracles of Life of arriving in the UK from China in the 1940s: ‘Looking at the English people around me, it was impossible to believe that they had won the war.’ I don’t know if we’re headed towards something like that — but it doesn’t seem at all impossible that I could be an old man before this town again resembles the one I knew as a young man.

One of the most enduring human follies is the sense that what you’re used to is a fact of nature rather than a fragile contingency of history. That includes neighbourhood restaurants. I gnawed those ribs of lamb right down to the bone.

Comments