Ian Fleming once said that a gentleman’s choice of timepiece said as much about him as his Savile Row suit. The latter part of that evaluation seems anachronistic now – after all, who apart from Jacob Rees-Mogg wears Savile Row suits with any regularity these days? But the idea of the watch as indicator of taste, status, wealth and much else besides is, arguably, still valid – and perhaps increasingly so.

Luxury watch sales are on the up and predicted to rise further – remarkable given the cost-of-living crisis, their inessential nature and an alarming rise in theft. Watches of Switzerland, who recently opened a multi-brand Canary Wharf showroom, saw revenue jump 17 per cent in the last quarter. Revenue for the whole sector is expected to rise by about 30 per cent between 2021 and 2028. Partly this is due to the unleashing of pent-up post-pandemic demand, but the market is clearly in rude health. Prized brands such as Rolex, Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe have lengthy waiting lists.

Another sign of buoyancy is the steady influx of new high-end watchmakers, many of whom are British. AnOrdain of Glasgow, whose handmade enamel dialed mechanical watches retail at a relatively modest £1,000, are getting hard to obtain. Also reportedly doing very well is the one-man microbrand Studio Underdog, whose colourful, whimsical creations are a snip at £500, Christopher Ward (£800+) and Bristol-based Frears (from around £3,000), all of which boast their British design and manufacturing credentials.

At the other end of the price scale in Staffordshire’s ‘Little Switzerland’ are the husband and wife team of Craig and Rebecca Struthers, whose exquisite bespoke offerings can run to six figures. Also feted and much sought after is the work of Japanese artisan Naoya Hida, who accepts ‘applications’ rather than orders (you may not be successful).

These names will mean little to the non-cognoscenti, which suggests that the appeal goes beyond pure big brand status symbol value. Simon Crompton of menswear blog Permanent Style sees the enduring popularity of luxury watches as driven by a variety of factors appealing to a variety of men. The show-off factor is certainly important for some (though that backfired on Emmanuel Macron recently), while the history and romance of heritage brands is seductive for others. Then there is the geeky technical side. There’s a curiously macho thrill in acquiring a piece of hand-assembled precision engineering and demonstrating mastery of such terms as bezel, indices, tourbillon and lugs to anyone who’ll listen.

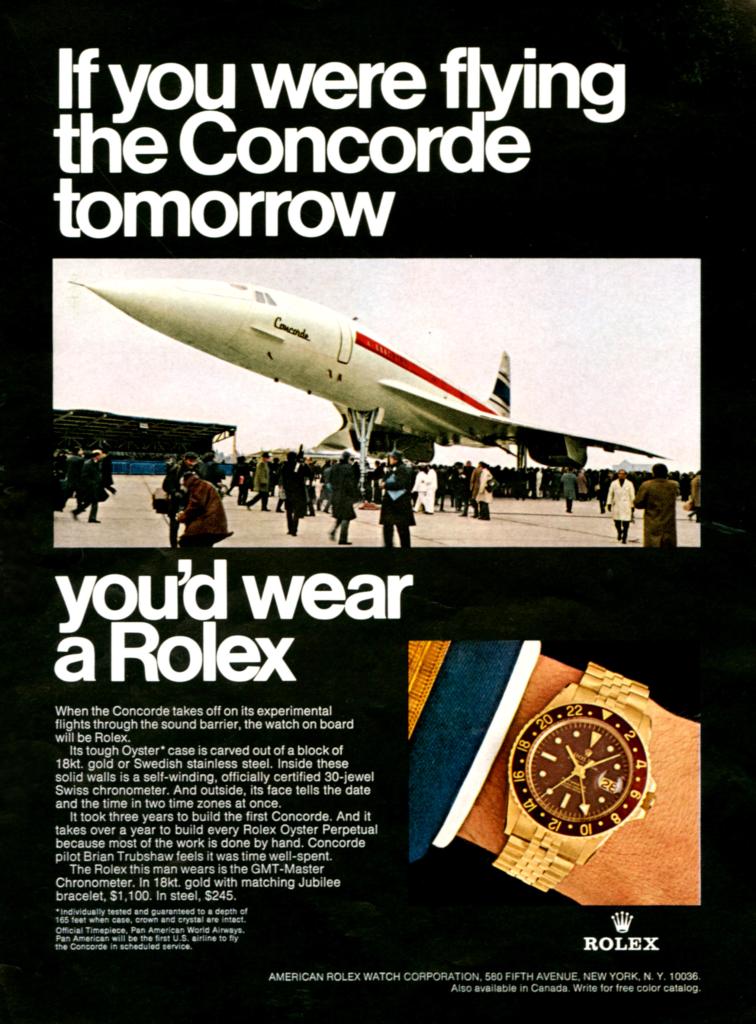

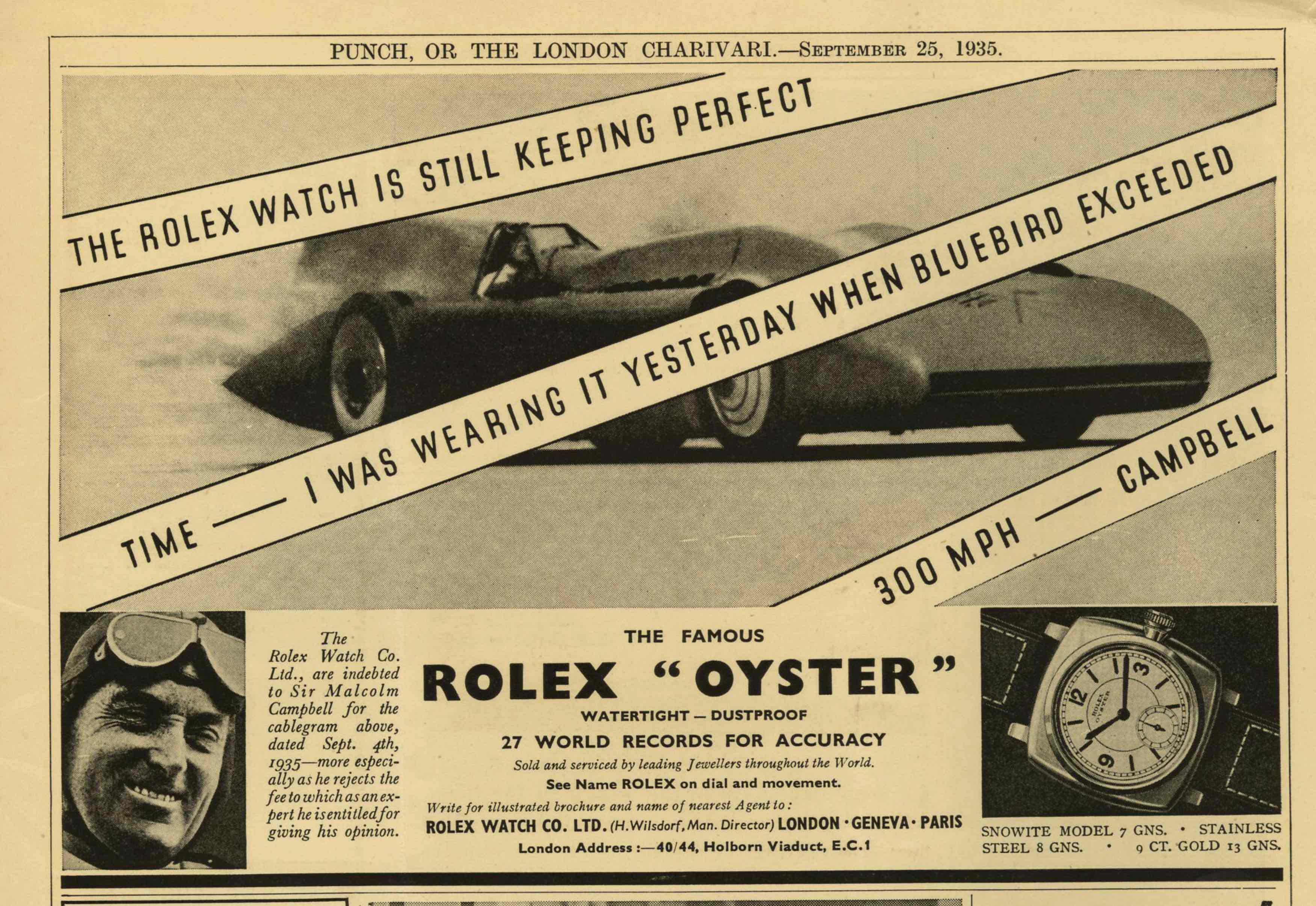

On a dull day, a Rolex Oyster Imperial can put you in touch with Edmund Hillary (who wore one on the ascent of Everest); a Tag Heuer Monaco places you on the starting grid at Le Mans

The high-end customer base seems to be expanding. Why now? Could it be that lockdown and working from home gave men with, well, time on their hands the chance to research what had been a mild interest and turn it into a serious hobby? Information has never been easier to come by. Witness the slick promotional videos of style guru and watch expert Mark Cho of the legendary menswear shop the Armoury and see if you can resist his infectious enthusiasm.

And could it also be that that our obsession with convenience and digitisation has started to wane? Hi-tech smartwatches no longer have the excitement of being either new or rare; gadgets that once promised liberty, from chores and unnecessary effort, have acquired a more sinister reputation as tracking devices, harvesting data on our daily activities. Do we control them, or do they control us?

Wearing a mechanical watch now feels more like genuine freedom, an escape from yet another screen (something also believed to be driving a resurgence in basic Casio watches). And it can be cherished and cared for, considerations which seem back in vogue. The Struthers credit BBC’s The Repair Shop with invigorating a love of craft and restoration (they make and restore). Their talk of ‘bringing watches back to life’ perhaps hints at part of the appeal: that a mechanical watch is a living thing (hands, face, a beating heart). Can you even have a smartwatch repaired?

Perhaps an expensive watch makes more financial sense than it might at first appear, too. Bespoke apparel can hardly be worn every day, and even with care will struggle to last a lifetime. But a luxury watch can be yours for life, and perhaps passed on to the next generation. They can also be investment assets: some high-end brands are believed to vet customers to prevent ‘flipping’ for profit on the secondhand market.

Of course, it is terribly indulgent to spends thousands on a watch, and some will be forever unconvinced. But is a little extravagance, a little fantasy really a bad thing? On a dull day, a Rolex Oyster Imperial can put you in touch with Edmund Hillary (who wore one on the ascent of Everest); a Tag Heuer Monaco places you on the starting grid at Le Mans or a Breitling Navitimer at the controls of a 747; and an Omega Speedmaster Professional lands you on the moon.

Luxury watches appeal to a certain kind of man, one of imagination, with an eye for detail, a respect for craft, an independence of spirit, and yes, a certain vanity and an obsessive streak. Ian Fleming knew the type. As he said of his most famous creation: ‘He could not just wear a watch. It had to be a Rolex.’

Comments