David Davis is the ghost at the coalition’s feast

And then, somewhere behind the arras, there is David Davis. Every Conservative party conference has an arras, and this year’s arras is a very pretty one, embroidered in sky blue and a pale yellow the shade of stale egg yolks, hardly yellow at all, depicting a touching scene from the award-winning homoerotic film Brokeback Mountain.

David Davis, a twice-failed leadership candidate, but a man somehow still in touch with the soul of the party, is somewhat less the focus of dissent right now than some expected him to be, although these are early days, of course. There is always someone behind the arras at Tory conferences — making acetic or embittered speeches at some fringe meeting, queuing up for the Today programme mobile studio, writhing with transgressed dignity. They are rarely so compelling a politician as Davis, though. Nor so canny.

Davis, unlike many on that distrait right-wing of the party he is oddly presumed to inhabit, supported the creation of the coalition, despite his famous Brokeback Mountain quip, a joke made in the first moments of that Cameron-Clegg joyous coming together. ‘Under those circumstances, yes, it was absolutely the right thing to do. In fact David (Cameron) called me to talk about it,’ he says, not mentioning that he was, when questioned about it at the time, more wry and humorous about the whole shebang than fervent for its success. There is a sweet irony, though: the one thing that cleaves the Lib Dems close to the Tories is the so-called liberty agenda, forged almost singlehandedly by David Davis. Without that there would be no ideological common purpose: Cameron has Davis to thank for the moral, if not pragmatic, support of many Lib Dems.

Two years ago, Davis executed the single most noble, principled and cheering act in politics in the past 25 years. He resigned his front-bench post and his parliamentary seat to make a stand on an issue on which, by a large majority, the country was utterly against him. This was about the length of time it was right and proper to detain terrorist suspects. Most of the country and almost all of his singularly right-wing Haltemprice and Howden constituency in the even more fabulously right-wing redoubt of East Yorkshire — where, traditionally, they like their Tory MPs to resemble the late Ian Smith and think Enoch was a bit of a pinko — wanted terrorist suspects shot on sight, never mind banged up for a few weeks. And yet, incredibly, he won — and while doing so turned the national public mood against the proposed 42-day rule, an astonishing triumph for political principle and the notion of an MP as campaigner at a time when the country loathed its Westminster rulers for being self-serving, bereft of principle and greedy.

His opponents, in the media and the Conservative party, argued that in resigning his seat he was somehow not a serious politician, that he had miscalculated, and that at worst he was motivated by pique or frustration at being beaten to the leader’s job by David Cameron. Well, even if that were the case, it was still a magnificent act. How many politicians succeed in changing public opinion these days — or would even want to do such a thing? Equally, there’s no doubt that he infuriated his party’s leadership and had himself written off by the political commentators. But hell, from behind the arras — to thine own self be true, etc.

‘If there had been an easier, cheaper, simpler way of making the point,’ Davis says now, ‘I would have done it. But there wasn’t. And when I resigned my seat there was at least one MP, now a member of the front bench, who offered to resign with me.’ He won’t tell me who it was. ‘You’d have a scoop then,’ he laughs.

The problems for Davis are twofold. First, he cannot for ever cling to the comfort of being adored as the Tory activist’s ideal Tory when he is, in truth, no such thing. For sure, there is stuff that is Monday Clubbish about him — he still supports capital punishment (‘but it will never happen; it’s a non-question really, maybe not with the electorate but with the people who matter. It’s a moral issue for me’) and is not terribly apologetic over having voted against the repeal of Section 28 and against the lowering of the age of consent for homosexuals. He is, so far as the constituency associations are concerned, agreeably rightish on social issues and economically small-statist. But there is an awful lot more to him than these slightly embarrassed genuflections to the golf-club whisky-sodden breast-beating old-school right would suggest. Yet he cleaves to his support within the Conservative rank and file, as if it is all that he has. When I suggest to him that he might end up a sort of superannuated Frank Field of the right, for ever a source of good and even brilliant ideas and yet deprived of any meaningful political power, he laughs uncomfortably and then slightly bristles, an unforeseen edge coming into his voice. Frank Field, he says a mite tetchily, does not have the support of his own party activists and MPs — which is undoubtedly true (Field has long been loathed by the left). ‘But I do,’ he adds, definitively. To which we might ask — and what good will it do you, David? The support of those people? That non-power power base which has served you so badly through two consecutive leadership elections? ‘The coalition still has to take notice of what I say or do,’ he finally says. Does it? I wonder if it really does. Why would it, right now? According to Davis, he was once described as a maverick statesman; but what use, in the end, is that?

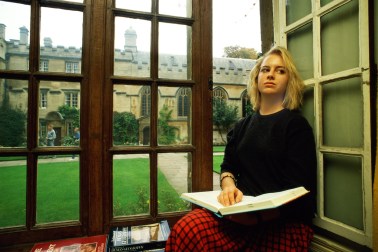

And the second problem is — can he remain semi-detached? He is outside the Cabinet and talks a little, in idealistic terms, of how a politician should not be judged upon the rung of the ladder which he has acquired. A proposition with which we might all agree. And yet in a House of Commons which is still dominated by the public school-educated Oxbridge apparatchik elite, by people who have never worked beyond the confines of the Portcullis House, you yearn for someone in high office with Davis’s edginess and sometimes difficult brilliance. ‘If I’m wanted,’ he says, ‘I’ll be there.’ Why would he not be wanted?

Comments