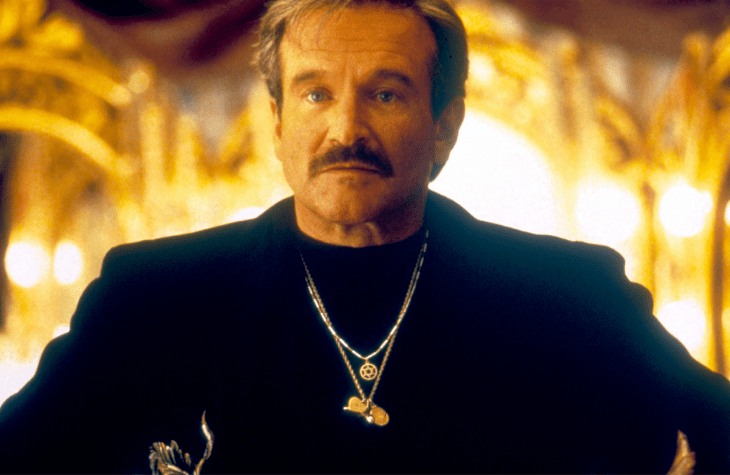

I recently rewatched The Birdcage, Mike Nichols’ pleasing farce of clashing values, a Hollywood adaption of Jean Poiret’s lighter, sharper 1973 play La Cage aux Folles. The son of drag club owner Armand Goldman (a dialled-up Robin Williams) has proposed to the daughter of Republican Senator Kevin Keeley (Gene Hackman, almost camper than Williams) and tries to arrange a dinner for the two families without Keeley discovering that Armand is gay. In the end, everyone learns to get along and some riotous slapstick disrupts the mildly preachy tone. It’s not Nichols’ best work but in 1996 it was a step up from the Four Fucks and a Funeral movies that monopolised queer cinema.

It struck me while revisiting this benign romp that its straightforward plot would be impenetrable to anyone under the age of 25. Why is Armand pretending to be straight? Why can’t Keeley find out he’s gay? Generation Z would deem it much more problematic that Armand owns a drag club and thus profits from transphobic misogyny. In fact, if The Birdcage was made today it would be the senator’s daughter striving to impress her fiance’s gay parents while concealing her father’s shameful secret: he believes marriage should be between a man and woman.

A lot has changed since 1996 and as the culture grew more inclusive of gays, it came to revile traditionalist hold-outs. Their worldview went from orthodoxy to punchline to nostalgia to ‘hate’ in a startlingly short space of time. That dread malediction now attaches to John Finnis, an Australian academic regarded by many as the foremost natural law scholar of the last 40 years. His work is required reading for any serious student of jurisprudence even if it can be, in places, assaultively contrary. (I spent a semester grappling with his Natural Law and Natural Rights as an undergraduate; his belief in legal moralism and the division of law from moral reasoning is where my drinking problem began.) Some students at Oxford, where Finnis is professor emeritus, aren’t too keen on him either and want him evicted from the spires. The Catholic philosopher has greatly sinned in his thoughts and in his words by reflecting the Church’s teaching on homosexuality in a number of scholarly articles. Sua culpa, sua culpa, sua maxima culpa.

Alex Benn and Daniel Taylor, two postgraduate students, are not in a forgiving mood. They are behind a petition demanding Finnis’s removal and an accompanying op-ed in the pitchfork-wielders’ journal of choice, the Guardian. They cite a 1994 article in which Finnis sets out the ‘standard modern position’ on homosexual conduct, namely that the law tolerates private same-sex intercourse but the state still asserts its right to encourage traditional sexual mores and discourage the promotion of homosexuality as an equally valid lifestyle. This, he continues, ‘involves a number of explicit or implicit judgments about the proper role of law and the compelling interests of political communities, and about the evil of homosexual conduct. Can these be defended by reflective, critical, publicly intelligible and rational arguments? I believe they can’. Strike one against the hate-thinker.

The next charge is that Finnis once analogised homosexual relations to ‘copulation of humans with animals’. He did, reasoning that ‘sexual acts are not unitive in their significance unless they are marital’ and all other conduct was ‘divorced from the actualising of an intelligible common good’. Strike two. A 2012 article published in a Catholic journal lamented the ‘virtual non-discussability’ of subjects including ‘the reversibility of sexual orientation or the relation if any between sexual orientation and child-abuse’. Strike three. An unholy trinity of bigotry.

Finnis’s musings would scandalise most secularists and there are plenty of Catholics who might wonder if he tanned the Communion wine before sitting down to write. He is a reactionary. What do you expect from a man who went back to Aristotle and Aquinas to resurrect natural law theory in the late 20th century? However, this treats Finnis’s views as ethos when his detractors consider them animus. They allege that Finnis ‘dehumanises’ homosexuals and say ‘LGBTQ+ students may be intimidated, stop contributing and learn less effectively’ in a seminar with him. Finnis is a 78-year-old professor of legal philosophy. I doubt he could tell you what an LGBTQ+ is, let alone single out any of the letters for opprobrium. Their objection is not so much that Finnis might utter one of his regressive opinions in the earshot of an LGBTQ+ student but that his very presence is somehow morally corrupting. ‘[T]his issue,’ the petition reads, ‘is about the kind of institutions that Oxford and other universities should be’.

Benn and Taylor contend that ‘students should not encounter [such views] from their teachers’ and rebuke other scholars who ‘argue that [these views] are… protected by “academic freedom”’, insisting the administration ‘draw a line when professors dehumanise disadvantaged groups’. Those scare quotes around academic freedom would be chilling but for the delicious revelation that anyone attending Oxford University considers themselves disadvantaged. It’s grim up North Parade.

The rub is not that these students are against ‘hate’ but that their definition is so expansive as to collapse the walls between what is contempt-promoting or verbally assaultive and what is merely obnoxious, offensive, irritating or politically incorrect. I read Finnis’s 1994 article as an undergraduate and it never occurred to me that I was being ‘dehumanised’. I was reading a scholarly text on the philosophy of law, a critique of certain ideas and a postulation of others. This is what I had gone to university for.

The petition accuses Finnis of ‘hateful statements’. Hate speech hinges in part on an understanding that certain characteristics (e.g. race or sexuality) are so intrinsic to the sense of self that abusive comments about them may be experienced as something akin to physical assault or threat by those marked by these characteristics. A T-shirt that reads ‘Burn in Hell, faggots’ may well be intimidating to some. Accord reasoned opinion and scholarship the same expressive value and you usurp ‘the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience’ for the liberty to argue according to the conscience of others. Note how even the most nuanced dissent in the transgender debate is framed as an existential threat to vulnerable trans youth. Centuries of tradition on individual freedom must make way for the inviolability of identity.

Of course, there is a transactional argument. Students are paying customers and entitled to demand bland neutrality from a service provider but applying that corporate standard to scholarship would prove career-ending for many academics. Benn and Taylor’s petition could easily be rewritten to require the dismissal of lecturers who ‘dehumanise’ Zionists and thus cause distress to students whose Zionism is no less central to their identity and who are an even tinier minority on campus than homosexuals. Put quote marks around John Finnis’ academic freedom and you put them round everyone’s.

The collapse of socialism was supposed to mark the triumph of the individual over the state but as identity politics has nudged economics aside the sphere of liberty has narrowed, not expanded. The gently liberal mores that have ordered social relations roughly since the 1960s are being shrugged off by a progressive culture in possession of revealed truth and impatient of agnostics. Like the legal moralists, they are in the business of ‘making men moral’ and just as zealous about discouraging blasphemy, regulating sexual behaviour and enforcing community standards. John Finnis’s ideas may be contemptible but they are ideas — something more than victimhood and endless acronyms, something that can be debated and debunked without resort to petitions for banishment. Progressives are not Armand Goldman, they’re Kevin Keeley.

Comments