Late last year, Heidi Crowter, a 27-year-old woman with Down syndrome, lost her court of appeal challenge over late-term abortions on grounds of serious foetal abnormalities. Abnormalities such as hers, that is.

The law in England, Wales and Scotland makes an exception to the 24-week time limit for abortion, permitting abortion all the way up to birth if there is ‘a substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped’. That includes unborn children who have Down syndrome.

This rule, Heidi argued, ‘tells me that I am not valued and of much less value than a person without Down syndrome’. She’s right. Current legislation stigmatises those living with Down syndrome by sending out a message their lives are not worth living and less valuable than the lives of the able-bodied.

The judges at the court of appeal disagreed. The perception so hurtful to Heidi – one rule for her, another for her able-bodied peer – did not, the judges found, by itself contravene article eight rights (to private and family life, enshrined in the European Convention on Human Rights).

Current legislation stigmatises those living with Down syndrome by sending out a message their lives are not worth living

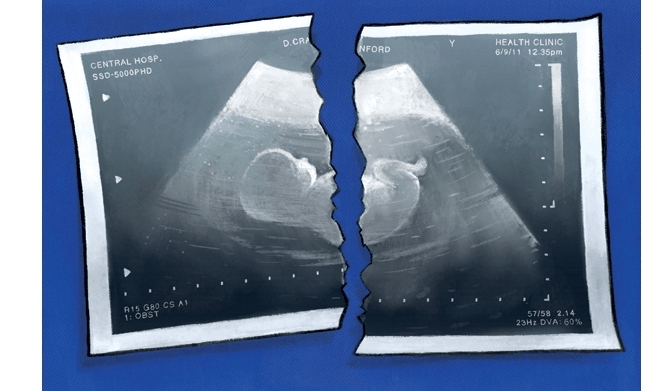

Heidi is not finished. She has now lodged a permission with the Supreme Court (and in due course would pursue this matter to Strasbourg). But already her case has thrown into the spotlight the painful ambiguities and profound controversies surrounding a practice firmly embedded within twenty-first century British society: genetic screening and selective abortion.

We are faced with the fact that pre-natal testing has become routine, as has the selective abortion which follows from it. In the UK 90 per cent of those diagnosed with Down’s syndrome are aborted. Before the advent of prenatal testing – whether via ultrasound technology (first employed for diagnostic use in 1956), or via amniocentesis (first introduced for Down’s syndrome in 1966), or via non-invasive pre-natal testing (available since 2012) – parents did not have to wrestle with the decision of whether to abort a child with physical or intellectual disabilities. Then, expecting parents of children with chromosomal deficiencies lived in blissful ignorance. Now, technology can place parents under an agonising burden – a fact which sufficiently impressed anthropologist Rayna Rapp in the 1980s to prompt her to confer the term ‘moral pioneers’ on such parents.

Take Joy Freeman’s experience. Halfway through her pregnancy Joy went in for a routine scan. She wasn’t expecting any problems. She wasn’t expecting a fright. No surprises please. So, the news her baby had spina bifida came as a shock. She wrote in the Guardian: ‘Diagnosis of an abnormality in your unborn baby propels you into a strange alternate universe where everyone around you seems callously happy. You are still outwardly pregnant, and people congratulate you, but you are living with the poisoned chalice of knowledge and choice’.

Parents of previous generations never had to live with this ‘poisoned chalice of knowledge and choice’. Yet even though the technology is new, the outlook which frequently informs decisions to selectively terminate is ancient. Late modernity may provide the means, but Greek tragedy still supplies the reason.

Lyndsay Werking-Yip is another mother whose 20-week scan came as a bombshell. Again, everything had been looking good. ‘We watched in amazement and excitement as the tech showed us all the precious growing parts of our baby girl: her spine, left hand, right ankle, ten fingers, ten toes, lips…’ Even the technician chimed in, ‘She looks perfect’. Lyndsay adds: ‘My heart swelled with pride when [the technician] added: “Your baby is being nice. She isn’t moving too much.”’ Towards the end of the scan, however, the technician’s tone changed. ‘“I see something,” the tech said. “I’m not sure what it is. Come back tomorrow.”’ The alarm prompted ‘a few weeks of agony’, with amniocentesis, a foetal MRI and multiple ultrasounds eventually revealing a diagnosis of ‘severe brain abnormalities’. Instead of brain matter, in the frontal lobe there was a small empty space. In addition, the baby had agenesis of the corpus callosum: the middle structure joining left and right hemispheres of the brain hadn’t developed properly. Eventually, the uncertainty (‘we knew the diagnosis but we didn’t know what it would mean for our daughter’s daily life’) was too much. As Lyndsay relays in her article in the New York Times:

My husband and I chose to end our child’s life… Our child would not be given a life of pain and suffering… At 23 weeks and six days into my pregnancy, I had a “late term” abortion. When people ask, “How could you?” I reply that allowing her to live would have been a fate worse than death. Her diagnosis was not fatal, not incompatible with the bare mechanics of a living body. But it was incompatible with a fulfilling life.’

The idea that an unfulfilling life can prove a fate worse than death is deeply rooted in Western culture. W.B. Yeats concluded his poem, ‘A Man Young and Old’, with his own translation of some profoundly stark lines spoken by the Chorus in Sophocles’ play, Oedipus at Colonus:

Never to have lived is best, ancient writers say;

Never to have drawn the breath of life, never to have

looked into the eye of day;

The second best’s a gay goodnight and quickly turn away.

The contention here is that life can sometimes be a fate worse than death.

In the great tragedians of fifth century Athens, the motifs are the same: ‘the shortness of heroic life’ and ‘the exposure of man to the murderousness and caprice of the inhuman’. The Gods are pitilessly indifferent; ‘we are punished far in excess of our guilt’; there is no consolation, no redemption, no restoration.

It’s not only parental justifications of selective terminations which are rooted in an Ancient Greek outlook. It’s the reigning view in academia too. Within the desultory sub-discipline that is bioethics, absolute tragedy is considered a live possibility. For example, in an essay entitled ‘Future People, Disability and Screening’, British bioethicist Jonathan Glover argues that ‘if a child is brought into the world with a disastrous disability, that child will have a life that is worse than no life’. While American bioethicist Laura Purdy maintains abortion activists legitimately see selective abortion ‘as a way to prevent the development of persons who are more likely to live miserable lives’.

Lynn Murray is the founder of Don’t Screen Us Out, a British lobbying organisation comprising 17,000 people with Down syndrome, their families and supporters. ‘It’s as if they are handing down a death sentence…’ says Murray, of clinicians tasked with delivering to expecting mothers news of a Down’s syndrome diagnosis. ‘I’m sorry’, clinicians will begin, heads hung to the side, ‘you must be devastated’. The sociologist Gareth Thomas concurs:

‘Defining Down’s syndrome as a risk, in turn, carries negative connotations; if something is a risk, it is to be feared and avoided. This helps produce and uphold the status of Down’s syndrome as a negative pregnancy outcome, ensuring that familiar scripts of reproductive misfortune remain intact.’

This was certainly Máire Lea-Wilson’s experience, a London-based accountant I recently interviewed whose son Aidan was a co-claimant in Heidi Crowter’s case. Máire was at 34 weeks’ gestation with Aidan when an obstetrician, initially worried about high blood pressure, sent her for an ultrasound, revealing her child to have ‘double bubble’ or duodenal atresia (a condition where the first portion of the bowel is blocked) as well as short femurs and a hypoplastic nasal bone – all conditions associated with Down’s syndrome. ‘Did you have screening?’ was the brusque response of another obstetrician. ‘Why not? Did it not matter to you?’

In the UK 90 per cent of those diagnosed with Down’s syndrome are aborted

But it wasn’t just the repeated offer of abortion which disconcerted Máire. The information she was given, so she tells me, ‘only highlighted the medical and negative social aspects of raising a child with Down’s syndrome’. A picture was painted which ‘made us feel incredibly scared and concerned for the future of our unborn son and for our older son’. The whole experience, Máire adds, ‘made us feel like Down’s syndrome must be very, very bad indeed and that perhaps bringing Aidan into the world would be unfair on him, unfair on our eldest son and unfair on us’.

How are we to evaluate the often-lethal application of the Greek tragic outlook to our contemporary encounter with disability? Well, it is, to use a fashionable term, ableist. ‘The canonical idea that some lives are not worth living results from the ableist conflation of disability with pain and suffering’, says the philosopher of disability Joel Michael Reynolds in a recent book. This conflation hinges upon a kind of ‘epistemic hubris’ – an unjustified assumption that the able-bodied can have sufficiently intimate knowledge of how men and women living with certain physical or intellectual disabilities experience the world to declare their lives to be fates worth than death. ‘We assume we know what suffering is’, writes American essayist Stanley Hauerwas, ‘because it is so common, but on analysis suffering turns out to be an extremely elusive subject’. And if this is true in general, how much more is it true of the particular experience of people with, say, intellectual disabilities?

Hauerwas continues:

‘No doubt, like everyone, the [intellectually disabled] suffer. Like us, they have accidents. Like us, they have colds, sores, and cancer. Like, us they are subject to natural disasters. But the question is whether they suffer from being [intellectually disabled]. We assume they suffer because of their [intellectual disabilities]… Yet… it is possible that that they are in fact taught by us that they are decisively disabled, and thus learn to suffer?’

My cousin Jack was born with a rare chromosol disorder. As Jack grew up, he couldn’t support his own weight, sit or talk. He was doubly incontinent. My uncle and aunt had to put drinks to his lips. Jack couldn’t look at you or smile at you. He was probably unaware even of who his parents were. But, as my aunt now reflects upon it, it is simply untrue that his life was one of chronic pain. She knew when Jack was in pain because he would cry. But that wasn’t all the time. Not at all. It was typically only when he had ear infections, and he would often stop crying when held. Did he suffer? Sarah is not so sure: ‘He wasn’t aware of his condition in relation to ours’. Apart from his ear infections he had a ‘carefree existence’ until he tragically died of pneumonia at the age of four. So, I simply will not accept that my cousin’s life, as intensely challenging as it often was for my uncle and aunt, constituted a life not worth living.

The German philosopher Josef Pieper gave a beautiful definition of love. Love, Pieper said, is turning to someone and saying, ‘It’s good that you exist; it’s good that you are in the world!’ Love, on that view, cannot be expressed any way you want. Love can never be compatible with killing. However merciful your motives, by aborting someone because they have Down syndrome you are doing the opposite of telling them that ‘it’s good that you exist’ or ‘I’m glad you’re here’.

Pieper’s definition of love is crucial too because it refuses to accept that even the most debilitating disability can ultimately cancel out the objective goodness of that person’s existence. And upon that basic thumbs-up to life our civilisation hangs. When we can’t as a society say ‘I’m glad you’re here’ to those with disabilities, even when they are in the womb, then we fail to live up to our promise as a people.

Comments