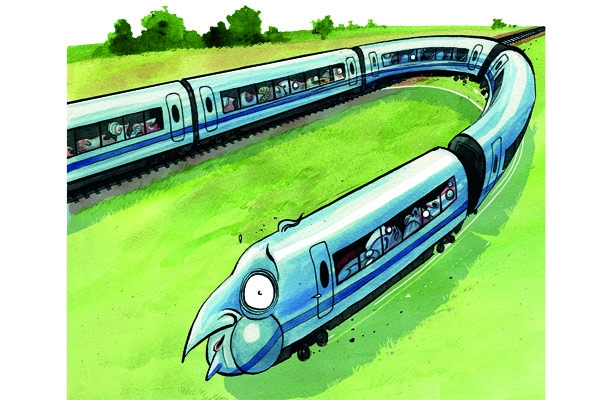

The fact that you cannot perform a U-turn in a train is one of the limitations of that form of transport. When the line ahead is blocked, locomotives form long queues, unable to go anywhere until the problem is solved. It is scarcely any easier performing a U-turn with a high-speed rail project, especially after you have spent several million pounds compensating people who live in blighted properties along its route, and several years promoting it as central to your vision for a modern Britain. But it is a U-turn which it is becoming increasingly clear that the government is now resigned to making.

To the outside world, ministers are admitting nothing. But the signals are there, for those with an eye to see them. The clearest sign came when a bill to instigate the project was left out of the Queen’s Speech. Four weeks ago, it emerged that the Cabinet Office was clinging on to a report which demolished the commercial logic for the scheme. A senior Treasury insider sums up the mood perfectly. ‘We do need improvements to Britain’s transport infrastructure, but whether HS2 is the best way to resolve this problem is not clear. Momentum is certainly draining.’

That the Treasury now appears to be backing away from HS2 is remarkable, because for the past few years George Osborne has been its biggest cheerleader. In 2006, the then shadow chancellor was won over to the idea of a rail grand projet during a ride on a magnetic levitation (maglev) train on a Japanese test track, and came back wanting to do the same for Britain. But the Chancellor’s enthusiasm has cooled. His former deputy, Philip Hammond, was also an HS2 advocate — but he has been replaced as Transport Secretary by Justine Greening. Unlike Hammond, she makes no attempt to argue with Tory MPs who criticise the project. She just listens sympathetically.

Word is getting out in Whitehall: HS2 has run out of supporters. No one will admit it in public, but very few ministers are defending it, either. Treasury civil servants were nervous enough about committing so much money at a time when the public finances could be about to be dealt yet another hammer blow by the euro crisis. One Tory minister says: ‘The project is effectively dead. The only thing keeping it on life support is David Cameron’s backing.’ Officially, of course, HS2 preparations are continuing — as the Prime Minister told Parliament on Wednesday. But whether he realises it or not, the project is being embalmed, prior to burial.

The story of the rise and fall of HS2 starts with one of those Concorde moments when British politicians become fixated on a vanity project divorced from any kind of financial sense. Tony Blair had been similarly won over during a presentation at Downing Street the previous year by a German-led consortium, Ultraspeed, which had proposed a 300mph maglev line from London to Glasgow.

Magnetic levitation trains are impressive on test tracks (except when they crash into stationary vehicles, as one did in Germany in 2006, killing 23 people), but they suffer from a rather obvious operational problem: they are completely incompatible with the railways which the world has been building for the past 180 years, meaning that no train could continue its journey on existing tracks. Blair went cool on the idea of a high-speed rail line from London to Scotland altogether. After commissioning two studies into the idea, one by its own quango, his government came to the conclusion that high-speed rail was simply too expensive.

George Osborne, however, continued to hanker for a high-speed rail project, albeit for a more conventional one with wheels. His boyish enthusiasm for fast trains then combined with what he saw as a political opportunity. With Labour having all but killed off the idea of high-speed rail, here was a chance, so he believed, for the Conservatives to reconnect with their long-lost territories in Scotland and the north.

David Cameron agreed, claiming rather preposterously in 2010 that a railway would help close the wealth gap between north and south: ‘If we think about governments of all colours, they have all failed over 50 years to deal with the north-south divide. With high-speed rail we have a real chance of cracking it.’ Spin doctors even took to calling HS2 the ‘one-nation line’. It is a meaningless phrase which begged the question: did they mean the line would facilitate the movement of businessmen to the provinces — or northerners travelling in the other direction, looking for work?

Ironically, given the anger now emanating from the Chilterns, another attraction of HS2 to the Tories was the desire to assuage to west London nimbys angered at proposals for a third runway at Heathrow, to which Labour had committed itself. The project also meshed with David Cameron’s green agenda — part of his mission to decontaminate the Tory brand, as he saw it.

When the proposal for HS2 was launched at the Conservative party conference in 2008, it caught Gordon Brown by surprise: he warmed to high-speed rail, leading to the setting up, in 2009, of HS2 Ltd, the government-owned company charged with delivering the project. HS2 had suddenly made the journey from an extravagance to an indispensable project which the country could not possibly do without.

That the £29 billion proposed cost worked out, per mile, as half as much again as the building of HS1, the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, and five times what the French had spent on the Paris to Strasbourg high-speed line which opened in 2007, ought to have condemned it from the beginning. It was clear that this was an extravagance that the private sector would not touch. But then that was 2009, the peak of Gordon Brown’s Keynesian spending splurge.

Rather odder was the Conservative backing for a project unsupported by a penny of private finance. When launching their proposals in 2008, the Conservatives did not specify a particular route and therefore did not appreciate that, in swapping a third Heathrow runway for a high-speed rail line, they had merely shunted a Nimby problem 20 miles down the M40. When resistance in the Chilterns did become apparent, however, it was at first welcomed by some in the Conservative camp, not least Steve Hilton, who is said to have relished a battle with the lords and ladies of the shires. What better way to appeal to northerners, it was argued, than to be seen to be putting their interests above those of posh residents of the Chilterns?

So HS2 conformed perfectly to Cameron’s wider agenda: to show target voters that the Conservatives had changed, by beating up their core supporters. It was a classic piece of ‘triangulation’, the political device pioneered by Bill Clinton: favour the interests of people who might possibly vote for you over the interests of those who will have to vote for you because they could not possibly bring themselves to vote for anyone else — in this case, owners of expensive properties in the Chilterns. Even a few months ago, this was the great political case for HS2: it picked a fight with the countryside, and helped Tories win urban votes.

But in recent months, Tory pollsters have noticed to their horror that their core voters are not trapped. Ukip is now vying with the Liberal Democrats to be Britain’s third most popular political party, helped by their campaigning against HS2.

But ultimately, far more damaging to the case for HS2 has been the lack of enthusiasm among those people it was supposed to impress: northerners, Midlanders and businesses. A recent opinion poll of northern residents by the think tank Policy Exchange cited only 30 per cent agreeing with the proposition that HS2 was a ‘good use of money’—with 53 per cent disagreeing. In the government’s consultation last year, fewer than a hundred businesses bothered to speak up for the project.

Neither have councils nor trade bodies in the north and Midland s given HS2 a ringing endorsement. Coventry city council — unsurprisingly, given that HS2 would bypass it — was concerned about the reduction in frequency of trains on the existing lines. Derby and Leicester councils were more interested in the electrification of the Midlands main line. Lichfield council complained that the plans were ‘fatally flawed’. Glasgow city council moaned that the high-speed line would stop a long way short of the Scottish border. And so it went on.

In order to believe that a high-speed rail line is the most pressing need in our transport system it is necessary to live the lifestyle of an MP. HS2 could not be better conceived to serve the interests of those who want to make regular day trips from London and who know they can always rely on a chauffeur-driven car to be waiting for them at the end of the train journey. It is even more attractive if, like George Osborne, your life and career have always revolved around a small patch of west London but you now find yourself having to make tedious journeys to a Cheshire constituency.

HS2 offers nothing to short-distance rail commuters, nor to those who must make daily journeys on a congested and often incoherent road system which has been starved of investment in recent years. Penny-pinching has put a halt to road schemes which have been screaming out for improvements, such as the A14 between Cambridge and Huntingdon, where north-to-south traffic, east-to-west traffic, huge fleets of juggernauts heading to and from Felixstowe container port and local traffic all have to squeeze on to a narrow dual carriageway that was never designed to carry a fraction of the traffic that it does. And anyway, experience of office has persuaded Osborne that Britain’s lack of air connections is a far greater threat to economic growth.

So what now? Given the trauma the government suffered for its explicit U-turn on pasties, it daren’t admit that its flagship infrastructure project was just as badly thought-through. So it has written itself a get-out clause by announcing that the scheme will be introduced as a hybrid bill next year. These often take 18 months to two years to become law. So the bill is likely to be left in limbo at the next general election, expected in May 2015. The bill would then automatically die, because it cannot be carried over to the next Parliament.

The government is right to let HS2 shunt into the sidings. But yet again, taxpayers will be left with a bill for an abortive infrastructure project — for the plans, the consultations, buying up property blighted by the scheme. The lack of commercial logic was evident from the start. Taxpayers would be better off if ministers who find themselves on trains knuckled down to work, and stopped daydreaming of vanity projects.

Ross Clark is on this week’s ‘View from 22’ podcast: spectator.co.uk/podcast

Comments