In l958, my hero in life, the person I most wanted to be, was Keith Dewhurst. I had arrived on the Manchester Evening Chronicle straight from Durham as a graduate trainee reporter, which was a laugh, as they did no training. Keith was the paper’s Manchester United reporter, knew all the players, went to all the games, and he wore a white raincoat with the collar turned up. Rapture.

I don’t think I exchanged more than a few words with him, just ogled his raincoat from afar. Have never met him since. If I were to, I am sure he would deny he ever wore a white raincoat. It was all part of my fantasy.

Now, after a long and distinguished career as a playwright and TV dramatist, he has returned to football with a book about a long gone team you have never heard of, unless you are awfully well up on football history, like what I is.

It is the story of a football team from the Lancashire town of Darwen, who in the third round of the FA Cup of 1879, playing their first ever game in London, astounded the football world by beating a posho team from the Home Counties called Remnants, going on to play Old Etonians in the next round.

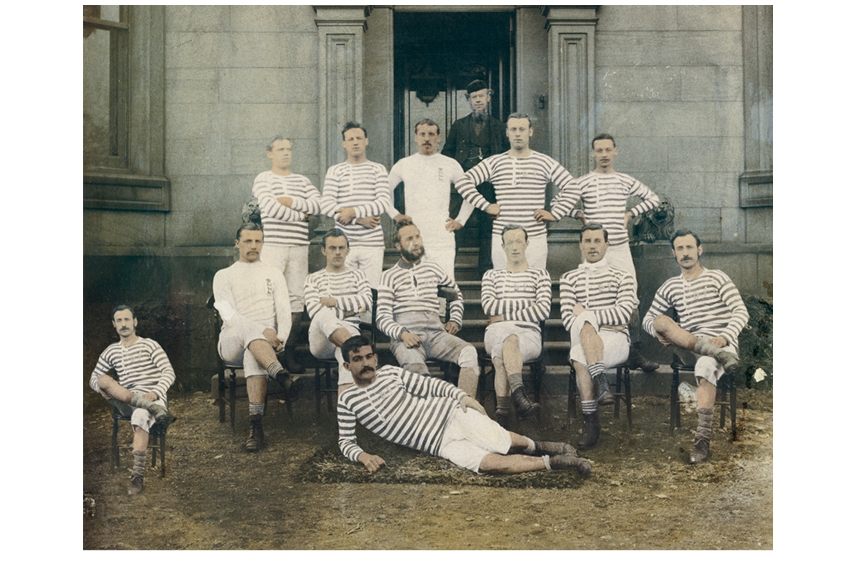

They managed two draws with the OEs, then got stuffed 6-2. A failure, in one sense, but a triumph in another. The OEs had refused to go North, so all three games were in London, a distance for the Darwen team of 1,230 miles, for which benefit concerts were held to raise money. How had these factory-worker types, who could not afford proper strips and wore different shirts and cut down trousers, who were three inches shorter and a stone lighter than their privileged opponents, been able to compete?

One reason was Darwen’s two excellent, nippy Scots — Fergus Suter and Jimmy Love. Scotsmen? How had they got there? Ah ha, tongues wagged. Given soft jobs in the town, wink wink, helped with their expenses, nudge nudge, using their delicate passing skills, perfected in Scotland, to confound the Old Etonian lumps, who, like most English footballers, were all kick and run, rushing up the field together.

It is now agreed, by most footer historians, that Suter and Love were football’s first professionals — which had been outlawed by the FA. It would ruin football as we know it, so the purists moaned, money would take over, plus bribery and corruption, players becoming mercenaries — all of which of course turned out to be spot on. Professionalism did come in not long after, in l885, when the FA bowed to the inevitable. The story of Darwen, therefore, has these fascinating historial elements — the beginning of professionalism, a change in the style of playing, the end of southern amateur Oxbridge chaps dominating football.

Keith, or I better call him Mr Dewhurst, as I did back in l958, has done an excellent research job in recreating the times and the tensions. He gets a little carried away by the social, economic and political history in Lancashire, some of it rather slapped down, making it hard to digest.The social history of football in the leading public schools is more interesting, and more relevant.

We all know, we clever clogs, the origin of the word soccer. It was a slang diminution of ‘association’, as in association football, as opposed to rugger, which comes from rugby football. I have always accepted, and have often written, that the first person to use the term was an Oxford undergraduate in the l880s called Charles Wreford-Brown, later a star of the Corinthians. Asked what he was going to do one afternoon, he said play soccer not rugger.

According to Keith, I mean Mr Dewhurst, the term had been used much earlier at Harrow. He does not say exactly when, but seems to suggest the 1840s. I bow to his superior knowledge. As I always used to …

Comments