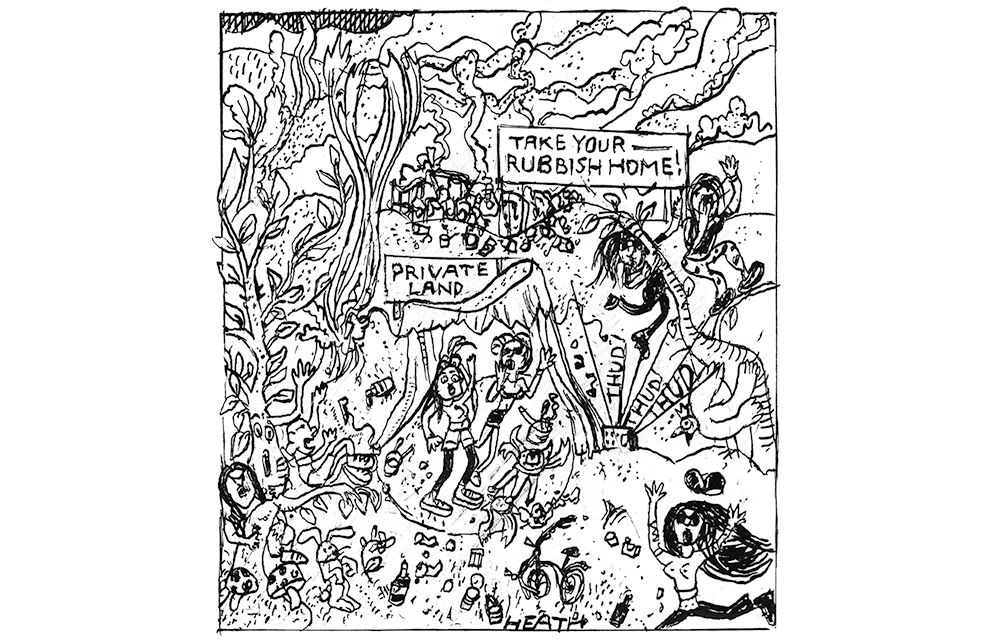

It’s not just bears that squat in the woods, as you’ll discover if you ever have the pleasure of a visit from wild campers. Other disfigurements to the land have included scorched patches of grass, which luckily didn’t become full-blown wildfires, branches severed from trees (presumably for wet firewood), stakes removed from young saplings (ditto), and the inevitable beer can and ‘disposable’ barbecue pyramid. I recently found a lacy, magenta-coloured bodice hanging from a tree, but that may have been left by an even wilder breed of camper.

So I have every sympathy for my fellow landowners who have the misfortune of eking out a living in the granite-strewn wastes of the Dartmoor National Park, where a legal challenge has just upheld the right to camp wildly, without permission.

Visitors can now camp overnight wherever they please, after the Court of Appeal decided that a right to ‘open-air recreation’ included setting up a tent and bedding down. As one campaigner from the charity The Stars Are for Everyone said: ‘Access to a night under the stars… now does not rely on the whims of individual landowners but is owned by ordinary people.’ As though those who steward the land are somehow not ordinary and that they exist to frustrate the lives of those who are.

In fact, few landowners would want to ban visitors outright; the warp and weft of rural living has always been enriched by a cast of hermits and eccentrics. In my childhood, there was an old lady named Miss Paulet who would roam the highways and byways in a gypsy caravan, pulled by a skewbald cob named Magpie that was nearly as old as her. She would occasionally call on my parents for a glass of sherry and a bath and once gave my father a piece of paper with the address of her next of kin scrawled on it – a marchioness with many acres of her own – in case she was found dead one day.

We have from time to time had tramps living in secluded parts of the estate and have had cordial relations with them. Here in Scotland, there is in fact a centuries-old tradition of cattle drovers, displaced Jacobites and other outdoor types camping pretty much where they please. There has never been a law of trespass, despite attempts by the newly devolved executive to pretend they had bestowed a ‘right to roam’. And most landowners were just fine with that, particularly as all sides tried to make it work, despite ever-increasing pressure from a growing population wanting access.

Lately, however, camping etiquette has disintegrated. Rousseauism has taken hold of leftist imaginations in a way not seen since the 1840s. It expresses itself in the neo-romanticism of the rewilding movement and the land-reforming zeal of the Extinction Rebellion mob. Egged on by the likes of George Monbiot and Chris Packham, confrontational wild camping neatly combines both causes for any eco-activist wanting trouble. The national parks, which are increasingly trampling over their indigenous landowners’ rights and livelihoods, provide benign environments where a sense of entitlement can be flaunted. Unlike national parks in countries such as the United States or even continental neighbours like France, ours have always been settled. Farmers carved the mosaic of wild and agricultural land, which became so noted for its beauty that it was protected. They need to continue to manage the countryside.

The irony is that we are all supposed to be straining to halt the climate emergency and the biodiversity crisis (see Monbiot, Packham et al). The woods now bristle with ‘regenerative’ cattle, posing yet another danger to campers turning up unannounced. Wild campers, who are by definition strangers, have no way of knowing whether the spot they have chosen to stake out is the last refuge of a natterjack toad or ghost orchid. If the authorities really thought about it, they would be supporting landowners and their attempts to channel the public on to paths and into campsites. Wildlife would then be disturbed as little as possible, and we would be less likely to suffer wildfires that turn our flora and fauna into atmospheric carbon.

Any wild-camping aficionado reading this will no doubt bristle with righteous indignation. They will be spluttering about ‘codes of conduct’ and ‘responsible access’. And yes, there are many who come and go leaving little more than a compressed patch on the grass where they pitched their tent. Every year, earnest young wild campers arrive on my land full of gratitude and assurances, brandishing shovels for, embarrassed cough, biological necessities. But even these well-meaning types have sometimes pitched under precarious dead trees, left standing for their benefits to the wildlife, which could have fallen at any time. Campers can avoid such dangers of the wild, if only they speak to landowners first.

Comments