Inside Tate Britain on Monday night, a fashionable London audience will applaud the award of the £25,000 Turner prize to whatever is judged the best thing a British artist under the age of 50 can come up with.

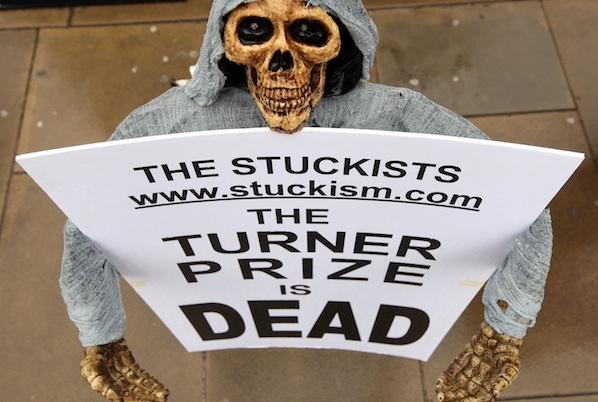

Standing outside will be a group of Stuckists protesting against the overlord who for nearly a quarter of a century has ruled this process. Sir Nicholas Serota chaired the prize until 2007, yet still retains his grip. It is he who has made figures such as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin so famous and rich. Yet this year, for the first time, there are finally signs that the Serotan winter is beginning to thaw.

The protestors rage against an art establishment that long ago embraced conceptual art as a dogma, taught that skill is a dirty word, turned art history into a vehicle for cultural Marxism and the rubbishing of genius, indoctrinated generations of art students with the belief that if you say it’s art then it’s art and that success is impossible without fluency in the language of conceptual art-speak. They shout about the nakedness of the emperors and allege plagiarism, nepotism and other misdeeds among the magic circle.

Yet till now public figures mostly toed the Serota line. Only a few — Robert Hughes, Brian Sewell — never ceased to mock and deride where deserved. The Jackdaw, a magazine offering a forum for independent views on the visual arts, has been brave and resolute in its defiance. But on the whole, the young and ambitious recognised that such heresy was no way to get a good degree, or become an artist, art critic, curator, gallerist or academic. The message was clear: conform, or die the professional death.

This started in 1974 when Michael Craig-Martin, a minimalist conceptualist, exhibited a glass of water standing on a wall-mounted shelf, called it ‘An Oak Tree’, and explained in the accompanying text that he had changed the physical substance (though not the appearance) of the glass of water into that of an oak tree. It signalled the supremacy of the artist’s intention over the object. ‘That piece is, I think,’ said Damien Hirst, ‘the greatest piece of conceptual sculpture, I still can’t get it out of my head.’

Craig-Martin was Hirst’s tutor and inspiration at Goldsmiths College and went on to be a Tate trustee: among his work in Tate Modern is what is called ‘an artist’s copy’ of ‘An Oak Tree’. The Australian National Gallery has the original, although to get it through customs, Craig-Martin had to admit it wasn’t actually an oak tree at all, but a glass of water. It is under such tutelage and Serota’s patronage that Turner prize art has flourished.

Even failing to win can make a career. Tracey Emin just missed out on the prize for her unmade bed, though she was subsequently chosen to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale with neon messages and attempts to draw her lady parts. The wealth this brought turned her — for tax reasons — into a fiscal Tory. She even donated a neon saying ‘More Passion’ to No. 10 Downing Street. She has become Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy, and a damehood surely beckons.

This year the shortlist offers Elizabeth Price’s 20-minute repetitive video showing an empty choir in a medieval church, the 1960s band the Shangri-Las and a fatal Woolworth’s fire. In Turner prize speak, this is an exploration of ‘our complex relationship to objects and consumer culture… through immersive virtual spaces’. Spartacus Chetwynd’s most memorable creation — other than her name — is some kindergarten performance art involving bells and glove puppets which allegedly ‘dissolves the boundary between spectator and participant’. Then there’s Luke Fowler’s mind-numbing 90-minutes of footage of the late R.D. Laing, which allegedly reveals ‘how the relationship between individuals and society changes through time’. Meanwhile, Paul Noble, the bookies’ choice, has overcome the disabling advantage of being able to draw by providing the conceptual art world with what the Turner jury described as ‘a dystopian world where people become turds and turds become people’. Indeed.

However, the good news this year is that at long last it’s the insiders who are on the run, and the outsiders who sense their day is coming. The Turner Prize has become a yawn, and there are whispers of criticism of Serota. Not that he is letting go. At 66, some think that it is time for him to retire gracefully. But Director of Tate (he eschews definite articles) is not going anywhere: in 2008 a grateful board of trustees gave him the unusual status of ‘permanent employee’.

Nevertheless, Director of Tate’s grip may be slipping. Will Gompertz, the BBC arts editor and previously the director of Tate Media, has breathlessly reported that many senior curators despise much of the art they have had to show. Too afraid to be named, they believed that museums, curators, auctioneers, collectors, dealers and artists were in a conspiracy — for financial reasons — to maintain the reputation of overrated brand-name artists.

Nicholas Penny, the director of the National Gallery, has finally said that he is unimpressed by conceptual and performance art. Dave Hickey, a famous American art critic, has quit a world he has called calcified, self-reverential and a hostage to collectors. And last week, Jackie Wullschläger, the Financial Times art critic, spoke out against the theory-driven jargon that legitimised everything and called for independent minds to seek out original, important and neglected art which does not require translators.

I have done my bit with a satirical crime novel about a Russian oligarch wreaking a bloody revenge on curators, critics, dealers and other pillars of the art world who have cheated him. It is a comic novel, but its subject is serious. People are finally admitting — and saying — that the Oak Tree is half empty.

Comments