Summer is the season most associated with the enjoyment of life. It’s when people forget their cares, down tools, and head for the beach to enjoy sunny days and sexy nights. That’s how it was for me anyway until I came close to life’s polar opposite – barely surviving two close brushes with death. So for me summers are now indelibly associated with a sudden end that I twice narrowly escaped.

Tearing off my soaking shirt, I stood bare-chested in the rain, feeling the same sense of mingled relief and ecstasy as if I were Caesar

The first close encounter with Mr Death came in the Dordogne. My wife, daughter, and I had hired a horse-drawn caravan to explore the highways and byways of that enchanting province. Apart from the difficulty of making our idle steed – let’s call him Dobbin – move any faster than a sedate plod, all was going well until the thunderclouds arrived.

Seeing that the skies were about to fall on our heads, I stupidly steered horse and caravan into a lay-by beneath one of those lines of tall trees that frequently abut rural roads in France, intending to sit the storm out. We had just halted when the storm burst in full fury. The rain poured down in torrents, lightning flashed, thunder crashed ominously. Then came a crack of doom louder than any I had ever heard. I have never been under artillery bombardment, but I imagine that is what it would feel like: it sounded as though we had been struck directly by a high-explosive shell.

What had actually happened was a lightning bolt hitting the caravan’s zinc roof. Fortunately for us, the caravan had rubber tyres which had earthed the lightning strike, leaving the three of us shaken but unharmed. Dobbin was not so sanguine. Shocked out of his normal indolent state, he reared up in terror between the caravan’s shafts and belted out on to the main road like the proverbial bat out of hell.

I was still on the caravan’s steering platform, wet reins in my hands, but Dobbin was completely beyond my control. He tore along the busy road, utterly oblivious of the screams of my wife and daughter or of my feeble attempts to rein him in. Having escaped death by lightning strike, we were now in imminent danger of ploughing into a speeding motor vehicle.

Eventually, the sheer weight of the caravan slowed Dobbin from a gallop to a trot and finally back to his normal ambling walk. It was now that I felt the aftermath of the adrenaline kicking in. Tearing off my soaking shirt, I stood bare-chested in the rain, feeling the same sense of mingled relief and ecstasy as if I were Caesar on his chariot leading a triumphant entry into Rome after one of his victories. Overcome by the sheer joy of having survived a real danger of death, I have never felt more tinglingly alive.

A few weeks later, I flew into a broiling Vienna, having landed a job with the English department of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF). Immediately upon my arrival, I made my way out to ORF’s headquarters in the leafy western suburbs of the city, only to be told to return to the capital’s centre to register my arrival with the police. (As in most continental European countries, in Austria the police need to be informed of the existence and whereabouts of everyone in their patch as a first priority.)

Wearily, I made my way back into town and was walking along a street called Marxergasse minding my own business when something struck my shoulder. At the same moment, I was aware from the corner of my eye of a large dark object falling into the roadway a bare metre from me. I looked more closely and was horrified to discover the body of a suited man, his head splattered bloodily across the asphalt. The immediate image that came into my mind was a pearl necklace with its beads broken across a piece of pink meat. What it actually was were the unfortunate guy’s teeth scattered over his brains. His head had shattered on impact and it was not, to say the least, a pretty sight.

I was wearing a newly purchased light summer jacket and removed it to cover the smashed cranium. I felt a pang of regret about the ruined jacket, but as with the horse and caravan, my overwhelming feeling was one of relief at having again survived a close encounter with death: a yard nearer to me and the falling body would have taken me with him. The object that had struck my shoulder was his shoe, which had detached during his descent. Instinctively, I wanted to reunite the shoe with his foot and bent down to retrieve it. My fingers slipped inside and I felt the sticky warmth of its now dead owner, a sensation that struck me as peculiarly horrible for some reason.

What I also found strangely significant was the reaction of other passers-by in the crowded street. Or rather their non-reaction. A few rubberneckers did gather in a knot to gaze vacantly at the body, but the cars in the road didn’t stop. Not a single one. They merely manoeuvred carefully around the messy remains (a bloody stain was spreading rapidly across my jacket) – and continued on their way.

I did the same and reported my presence at the police station. Or I did after first reporting the suicide. Once the initial shock had worn off, I felt a strong connection to the dead man who had so nearly taken my life too and – my journalistic curiosity aroused – I resolved to find out all I could about him and discover why he had ended his existence so brutally.

Diligent inquiries gave me some of the answers. The imposing building I had been passing at that moment was Austria’s Forestry Ministry, which in such a well-wooded country plays an important part in its economy. The dead man had been a senior beamte or civil servant there. It emerged that he had been operating some sort of scheme to divert cash from the timber industry into his own pocket, but upon reaching compulsory retirement age, he realised that the scam would be discovered by his successor and rather than suffer inevitable disgrace and imprisonment, he had leapt from an office window on the fourth floor.

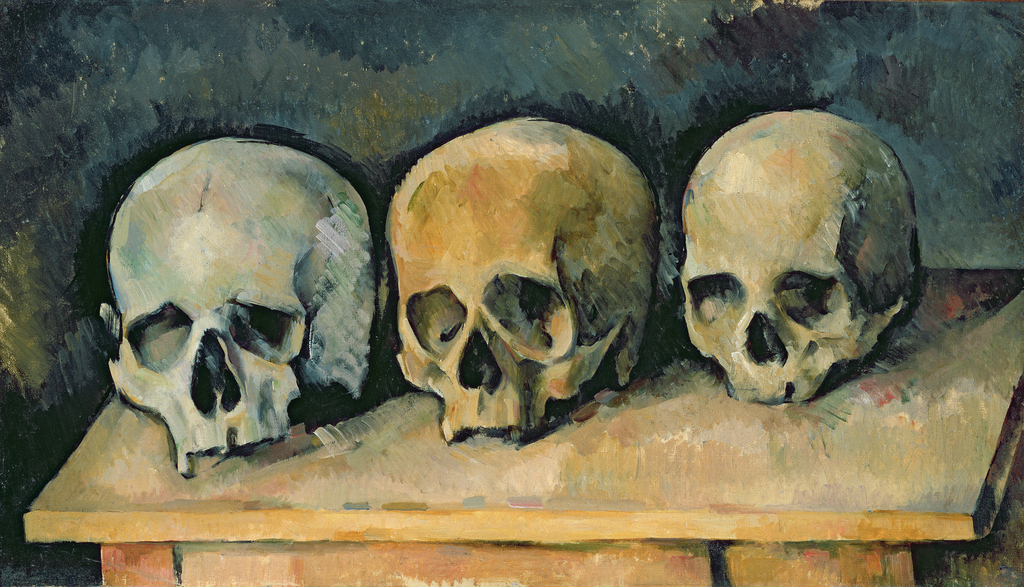

Before his misdeeds had been exposed, the Ministry had honoured their departed colleague in a very Austrian way: by unfurling a long black banner from the window from which he had jumped. Austria is a country much possessed by death and such a tribute – macabre in British eyes – is quite typical. So that is the story of my two close brushes with Mr Death. When I encounter him for a third time, I may not be so lucky.

Comments