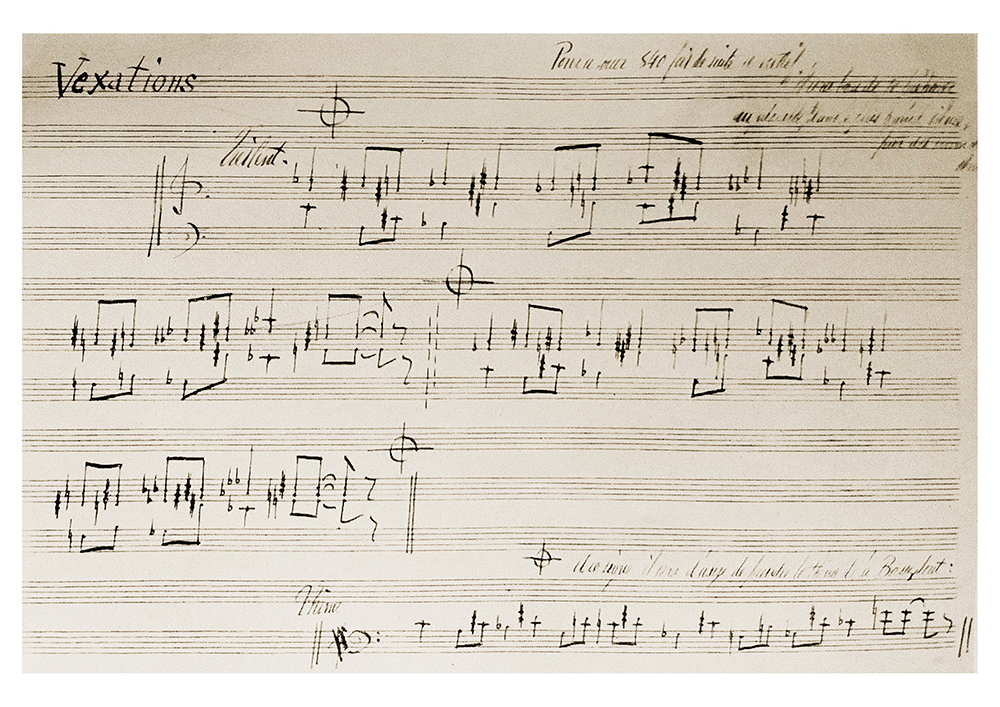

Once Igor Levit starts playing Erik Satie at 10 a.m. on 24 April at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, he can expect to be there for a long time. Satie’s Vexations is a piece that looks innocent enough, like butter wouldn’t melt in its composer’s ears. A doleful 18-note theme in the bass is filled in with stately, chorale-like notes in the right hand; the theme repeats, followed by the same chorale except turned upside-down. Nothing too strenuous so far. But Satie’s enigmatic inscription ‘To play this motif 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities’ mixes up the variables. Taking him to the letter of his word adds up to a performance duration of anywhere between 14 to 20 hours.

You can’t help but wonder – as with those unfortunate astronauts until recently stranded in space – how the most basic bodily functions will be accommodated as Levit attempts to defy basic concert-hall gravity. John Cage, who organised the first performance of Vexations in New York in September 1963, deployed a relay team of pianists – including David Tudor, Joshua Rifkin, David Del Tredici and John Cale, soon to become a member of the Velvet Underground – and even Howard Klein, dispatched by the New York Times to review the event, found himself roped into the performance. Vexations solo, though, is a whole other matter. After his performance Cage declared: ‘I felt different than I had ever felt before’, but when the Australian pianist Peter Evans attempted a solo rendition in 1970, the experience spooked him to the core. ‘I felt each repetition slowly wearing my mind away. I had to stop,’ he recalled. ‘People who play it do so at their own peril.’

Levit won’t be on his own entirely. The performance is trailed as ‘directed and co-devised’ by Marina Abramovic. Although precise details are being kept under wraps, their shared concept seems to involve having the set and lighting slowly dissolve, and encouraging the audience to move gradually closer to the stage. While not wanting to prejudge anything, transforming Vexations – pure ear-art – into something visual, with a hint of theatre, could undermine everything the piece was set up to achieve.

Satie wrote Vexations around 1893-4, when he was 28, and suffering the most painful bout of unrequited love in French music since Hector Berlioz’s failure to score with Harriet Smithson led him to score the Symphonie fantastique. At the height of Satie’s affair with Suzanne Valadon – a painter whose work was much admired by Degas and Renoir – she moved into a room next to his in Montmartre. But his obsessive behaviour proved too much and after six months Valadon was gone, and Satie never fully recovered from the trauma.

By then he had already composed much of the music he is best known for today, including those three ubiquitous piano miniatures he called Gymnopédies. Even in these most popular works, however, there’s a peculiar obsessive quality. The Gymnopédies are not so much a theme and variations, as a hollowed-out melodic husk viewed from three different perspectives, as though written to test the theory that insanity is about doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Then with Vexations Satie went one stage further and twisted musical grammar against itself.

As modern composition would work itself out by the mid 20th-century, repetition – in the work of Steve Reich, Philip Glass and Henryk Gorecki – was supposed to offer refuge, to those who sought it, from what was considered to be head-spinning complexity typified by Boulez and Stockhausen. Vexations offered literal repetition of notes; but also repeated cycles of disorientation. Satie’s theme, inching forwards, might have been easy enough to follow but he draped it in a coating of slippery, vertigo-inducing chromatic harmony, like blocks of primary colour embroidered with enough blurry shades of off reds, blues and greens to muddle the brain and make the eyes cross. As Vexations unfolds, familiar markers reappear but are pulled inside the harmonic quicksand opening around them. Instead of hearing what is there, you’re tricked into hearing what isn’t there. Disorientation smudges into pure brain fog; ears begin to hallucinate.

Satie did his utmost to make his Vexations score user-unfriendly and impossible to memorise

Ordinarily, composers take tremendous pride in making their intentions unambiguously clear as they notate their music. Satie, though, as he challenged anyone listening to keep their place, did his utmost to make his Vexations score user-unfriendly and impossible to memorise; anyone who played his piece was destined to be dragged inside his own loops of compulsive obsession.

Satie achieved this by upending some of the more arcane conventions of music theory, the fact that on a piano keyboard, for example, to sound the note E flat you press the same key as D sharp. Normally having E flat and D sharp coexist is a no-no, to be dodged like having different generations of Doctor Who meet. But Satie stuffed this score full of what musicians would term note ‘misspellings’. Non-musicians struggling to hear the difference might imagine this page, its words arranged to form sentences, with punctuation allowing their rhythms to breathe, written instead with randomly dropped in punctuation points and with words deliberately confronted with their commonly confused spellings – ‘to, keep their plaice place., two: keep there place plaice; too keep they’re place;’. The words might sound vaguely right, but the inscription of them is intentionally obfuscatory, calculated to throw the performer off the scent.

Why Satie forced musical language into this distorting hall of mirrors comes back to the breakdown in his relationship with Suzanne Valadon – and the breakdown in his relationship with romanticism. As the last years of the 19th century rolled into the 20th, Satie looked on with despair at the hold that Richard Wagner’s music dramas had over French composers, Saint-Saëns his particular bugbear. Wagner used music to express a narrative, to plot a story, in which chords and leitmotifs were tagged to represent characters and emotional currents. In 1892 Satie announced a new anti-Wagnerian opera Le bâtard de Tristan – but never came round to writing the music.

The idea put about by the likes of Reginald Goodall, that any conductor of Das Rheingold – the first opera of The Ring – should already have the climax of Götterdämmerung in mind as a ‘goal’, would have been anathema to Satie. Ditto the orgasm metaphor at the heart of Tristan und Isolde: the climactic, champagne-popping-out-of-the-bottle tension-and-release of the Tristan chord. German psychosexual neurosis was never Satie’s bag.

Vexations, instead, expresses loss; it ruminates over the sensation that there’s no way back. Its melody is stated explicitly, but those chromatic distortions maintain distance; the more you attempt to penetrate its surface, the further away it moves. Note relations in Wagner draw you into human relations to an almost unseemly degree; in the alienating drama of Vexations they push you back.

One theory about why Satie opted for 840 repetitions – why not 740 or 940? – proposes that he recognised it as a number with sacred significance in numerology. Locked in a cycle of endless pain and frustration, he wasn’t beyond invoking ancient, sacred, mindful mantras. He had fallen in with neo-Rosicrucian occultists Ordre de la Rose-Croix Catholique du Temple et du Graal, for whom he wrote some characteristically logic-upended fanfares. Then, in 1893, the same year as Vexations, deciding this organisation wasn’t quite occult enough, a little too à la mode, he formed a church of his own – Église Métropolitaine d’art of Jésus Conducteur. His tiny room in Montmartre became its Abbey, from where Satie issued newsletters proclaiming the spiritually cleansing benefits of sacrifice and poverty, written in a deliberately tub-thumping cod-arcane French.

Nobody knows whether Vexations was performed during the composer’s lifetime, but the piece came to John Cage’s notice via composer Henri Sauguet, a friend of Satie’s. Cage regarded Satie as a kindred spirit. In 1917 Satie started writing what he would come to call ‘furniture music’, designed to dissolve into the surrounding ambience of a space; in 1952 Cage’s 4’33” – too often mistakenly called his ‘silent piece’ – put a frame around sounds that already existed in a room. Cage’s New York marathon kickstarted a tradition of Vexations performances, most often done in relay form (Cage also pioneered a kind of anti-dynamic ticket pricing scheme in 1963: you paid $5 to enter the hall, but for every 20 minutes an audience member stayed, they were refunded 5 cents). A 2017 performance at the Guggenheim Museum in New York recalled Del Tredici, Rifkin, Philip Corner and Christian Wolff from Cage’s original team; there was a flurry of excitement in 2004 when it was announced that Yoko Ono would be contributing to a performance that year at the Barbican, the disappointment hard to hide when it turned out not to be that Yoko Ono.

The world into which Levit brings Vexations has, naturally, moved on. There was always a tendency for record labels, who you hoped might know better, to market Satie as chill-out aural bliss; Gymnopédies played with a sugary tone and drizzled with plenty of studio reverb. Now we live in a culture in which chill-out is king, where, as the American journalist Liz Pelly argues in her excellent recent book Mood Machine, musicians consciously tailor their music to fit the algorithms of Spotify chill-out playlists. The rippling doodles of Max Richter, Ludovico Einaudi and Alexis Ffrench tint the air with insipid soundbites, and you wonder what happened to the idea that music was about stimulating the mind, about awaking the senses, not sending them to sleep. Trying to chill out to Vexations would be like trying to foxtrot to free-form jazz. It’s a piece, like Charles Ives’s visionary The Unanswered Question (1908), that anticipated and argued through subsequent fault-lines within the music that followed it. Ives’s piece about the approaching tension between tonality and atonality was left merely unanswered – Vexations still feels unanswerable, the most inscrutable compositional enigma of them all.

Event

Spectator Writers’ Dinner with Richard Bratby

Igor Levit performs Vexations at Queen Elizabeth Hall on 24 April.

Comments