Recent acquisition of some insanely expensive hearing aids aimed at helping me out in cacophonous restaurants has set me thinking about the extent that modern life allows us to filter our intake of noise. This is big business. As sirens wail and Marvel blockbusters and rock concerts crash through legal decibel levels, controlling sound levels has become an increasingly sophisticated operation, abetted by everything from silicone pastilles and the volume-control knob to the wireless earbud.

The National Theatre has virtually given up on ‘natural’ sound

Concert halls and opera houses remain havens of what one might call ‘natural’ acoustics, places where the alchemy of balancing convex and concave surfaces with reflective and absorbent materials creates an environment in which reverberating warmth can coexist with clarity and a whisper can carry as far as a shout. London is blessed with the Wigmore Hall and Royal Opera House in this respect (the Royal Albert, Royal Festival and Barbican halls are generally deemed unhelpful by performers, if not audiences). Although it remains a point of dignity that in such venues classical musicians aren’t electronically amplified – they refuse to, as it were, cheat with a bionic boost – it’s a principle for which Joe Public will never give them credit. But just put a Wagnerian soprano such as Lise Davidsen singing, undoctored, alongside a belter such as Adele, and Joe would be stunned by the comparative puniness of the latter’s vocal production.

In theatres, it’s a different story: the magnificent roar of a Donald Wolfit or Alan Howard, organically generated and projected, is a thing of the past. Look for the tell-tale credit ‘sound designer’ halfway down the billing: it can be evidence that the actors will be communicating through an invisible cellophane layer that gives an entirely manufactured sheen to the words they are uttering, allowing them to go sotto voce and pass Marlon Brando mumbling off as emotional authenticity. In many cases it is, frankly, a bit of a cheat, and it’s bad for audiences too, making them more reliant on the aural equivalent of wrinkle-free Photoshop fakery.

For musicals the practice can of course be justified, because even the hardiest show singers need to use their vocal cords sparingly over eight shows a week (opera singers only do three at most). Mary Martin may have starred in an unmiked South Pacific at Drury Lane in 1951 without taking a single performance off in a year, but that’s inconceivable now. (Smaller pit bands, tougher vocal training and audiences with lower expectations offer a partial explanation for such resilience.)

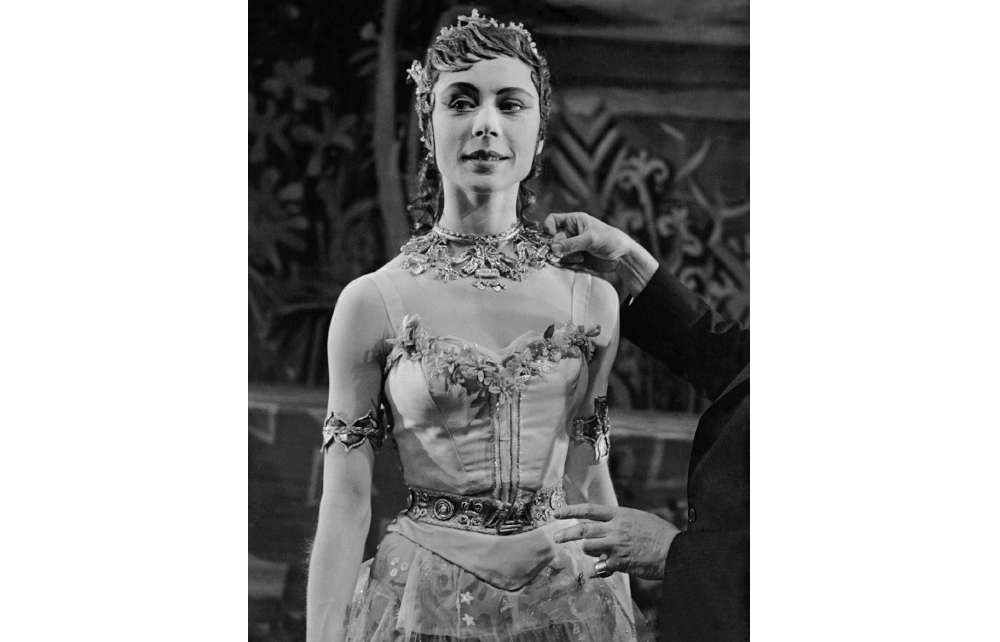

Quite how or when amplified sound made its advance is a mystery. We do know, however, that My Fair Lady at Drury Lane in 1958 used a row of floor (or ‘float’) microphones: these created pools of amplified sound which, according to Julie Andrews’s memoir, had an unfortunate tendency to pick up all manner of stray noise, not least Rex Harrison’s persistent flatulence. In 1961, when the ballerina Svetlana Beriosova was required to recite some poetry in the course of dancing Frederick Ashton’s Persephone at Covent Garden, a primitive body mic exploded and set fire to her costume. Five years later Barbra Streisand hit London in Funny Girl. Worried that her surprisingly small voice wouldn’t carry, she wore a mic in her cleavage – nobody else in the cast was permitted any amplification. By the 1970s rock musicals such as Hair and Evita were making more liberal use of hand-held mics, and reproducing the hi-fi quality of your stereo system became the goal.

Today, total miking is the norm for musicals. Each performer will be individually wired up to a tiny headset tactfully concealed, usually in the hairline, linked by cable to a transmitter taped to the back or thigh and mixed via a console at the rear of the auditorium to strategically placed speakers. It’s a delicate business. You can’t mic selectively: mic one, and you have to mic all, in order to avoid a two-tier effect. It’s crucial to keep the kit away from sweat – ‘the great enemy’ according to Terry Jardine, chairman of industry-leader Autograph Sound – because it muffles the higher frequencies. Something called ‘feedback colouration’ – the microphone in effect echoing itself – is another bugbear. And everything is made more complicated by the actor’s every movement changing the direction of the sound.

Jardine insists that it’s not a simple matter of providing the audience with a massive hearing aid. ‘We’re not so much turning up the volume as creating an atmosphere,’ he says, pointing to the landscape of spooky sonic effects that accompanied the success of fantasy shows such as The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and The Ocean at the End of the Lane. Directors such as Jamie Lloyd, Katie Mitchell, Robert Icke and Simon McBurney have all embraced the potential of this technology wholeheartedly, even if none have gone quite as far as Max Webster, whose Donmar Warehouse production of Macbeth requires audiences to wear binaural headphones through which every ghostly creak is radioed with hyperreal three-dimensional intensity. Even a one-man version of a Chekhov play can be coated in electrically powered artifice: for Andrew Scott’s Vanya, sound designer Dan Balfour sewed two mics into the collar on Scott’s shirt, and planted further invisible mics like Soviet bugs all over the set: ‘one for the kettle, one for the sink, one for the gun, one for the door, one for the metronome, two for the piano, three for the curtain rail’, and so on, making everything with which Scott interacted ‘pop’ vibrantly, on a level with his amplified speaking voice.

All this suggests an unstoppable trend. The National Theatre has virtually given up on ‘natural’ sound. It has always had acoustic problems with the Olivier auditorium, where concrete walls deaden audibility at its upper level. Various structural alterations and interventions have been attempted, none of them successful, and about 20 years ago, the management succumbed to head mics – or ‘sound reinforcement’, as they euphemistically put it. This is now ubiquitous throughout productions in the Lyttelton and Dorfman auditoriums as well. The last bastions standing out against electronic voice wizardry are the Royal Shakespeare Company (‘except in rare cases’) and Shakespeare’s Globe. The Almeida – capacity: 300 – is using it for The Years, with a cast of five. How much does this matter? The ability to throw your voice to the back of the gallery used to be a point of professional honour. Asked for advice on successful acting, the clarion Robert Stephens replied briskly ‘Speak up!’, and the likes of Judi Dench and Michael Gambon would regard the crutch of a head mic with disdain. But the young are growing as lazy about the art of projecting as drama schools are being casual about teaching it.

It’s right that the Olivier Awards now recognise the considerable achievements of sound designers, but something of the viscerally direct communication at the heart of the theatrical experience is being sacrificed to their ingenuity. Our ears are losing touch with the real thing.

Comments