Quizzed about pop by the teen music magazine Smash Hits in 1987, the year of her third consecutive electoral victory, Margaret Thatcher singled out ‘Telstar’, a chart-topper from a quarter of a century earlier, for special praise. She pronounced it ‘a lovely song… I absolutely loved that. The Tornados, yes.’

As a whizzily futuristic sounding instrumental ode to a transatlantic communications satellite, and only the second British recording to top the American Billboard charts, its charm for Thatcher was perhaps as much political as musical. That it was the work of an independent producer might also have appealed to her love of freewheeling, self-reliant private enterprise. Roger George ‘Joe’ Meek largely eschewed major label studios to record in a makeshift set-up in his flat above a leather goods shop at 304 Holloway Road.

Rather less on message for the espouser of family values, however, was that Meek, in 1963, was fined for ‘importuning for an immoral purpose’ at the public lavatories at Madras Place. This was a notorious ‘cottage’ not far from his home, frequented by gay men seeking casual sex. And just four years later, on 3 February 1967, Meek would murder his landlady, Mrs Violet Shenton, blasting her with a double-barrelled shotgun following a row over the rent book, before turning the weapon on himself.

Darryl W. Bullock, who died in December, profiled Meek in his 2021 book The Velvet Mafia: The Gay Men Who Ran the Swinging Sixties, alongside such contemporaries as Larry Parnes, Robert Stigwood, Joseph Lockwood and Brian Epstein – all of whom reappear here. But this book is the first standalone biography of Meek for more than 30 years. In that time, the producer has been the subject of at least two documentaries, a play and a biopic, and has appeared fictionalised in crime novels by the likes of Jake Arnott and Cathi Unsworth. He has also been lauded as an audio genius, rather than mocked for his gimmicky effects – a weakness for speeding up vocals being a bit of a call sign.

On 3 February 1967, Meek murdered his landlady, blasting her with a shotgun after a row over rent

Bullock dismisses some of the wilder conspiracy theories that have flourished about that grisly day in February. Most of these feature the Kray twins and their supposed attempts to muscle in on managing the Tornados – by then decidedly past it and devoid of any of the original members. We do, however, learn of the eerie coincidence that Phil Spector, the similarly volatile American record producer whom Meek once accused of stealing his ideas, went on to shoot the actor Lana Clarkson on the same day in February in 2003.

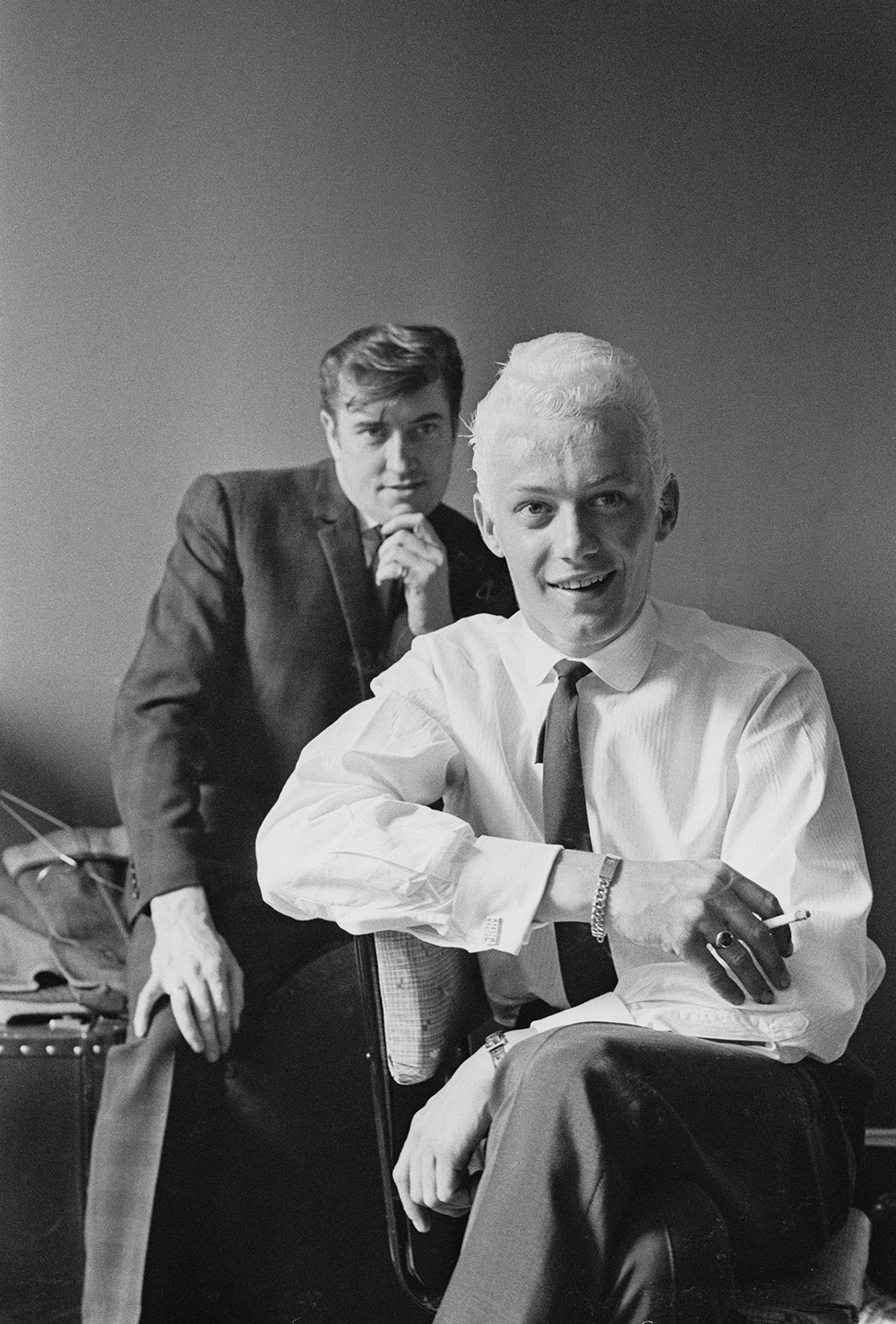

Bullock crowns Meek ‘the Wizard of Odd’, and the producer’s substantial output certainly showed a marked interest in the otherworldly and interplanetary, with the Wild West, ancient Egypt and the Anglo-Saxons thrown in for good measure. Seances in graveyards to commune with Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran and Ramses the Great were among Meek’s surefire means of generating hits for Mike Berry and Heinz Burt. The latter was a Southampton supermarket bacon-slicer turned Tornado bassist who was groomed by an infatuated Meek for solo singing success. Meek encouraged him to emphasise his Germanic heritage by bleaching his hair platinum blond. That Burt could barely hold a note, and faced a nightly barrage of tins of baked beans being thrown at him by teddy boys in dance halls across the land, was beside the point. ‘Just Like Eddie’ – penned as a tribute to Cochran by Geoff Goddard with help from the ‘other side’ – would see Burt land in the top five. But it was Burt’s shotgun which subsequently dealt the fatal blow to the whole enterprise.

Bullock’s book emphasises how driven and phenomenally productive Meek was – though the amphetamines he ate like Smarties severely damaged his mental health. Some 67 tea chests full of tape reels were found after his death, the contents of which are only now being released.

Equally apparent is just how weird the pre-Beatles world of pop was. This was a time when the future Fab Four knob-twiddler George Martin was hailed as a musical visionary for signing the pianist Mrs Mills, ‘a 43-year-old east London secretary’, as a rival to the million-selling ‘queen of ragtime key-thumping’, Winifred Atwell. Meek, like many others, would pass on the Beatles. Though he remained friendly with Epstein, it’s clear that he initially struggled to adjust to the new musical landscape. He was reduced to recording sessions with the Pete Best Four, led by the drummer whom Martin, Lennon and McCartney had deemed surplus to requirements; and he scoured his native Gloucestershire and the West Midlands for alternatives to the Merseybeat boom with somewhat mixed results.

Yet the roll call of musicians who clambered up the stairs of 304 Holloway Road to lay down tracks in Meek’s living room, stairwell and even toilet (favoured for its echo), is prestigious. They included Tom Jones, Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page, Deep Purple’s Ritchie Blackmore, Steve Howe of Yes and Charles Hodges of Chas and Dave cockney duo fame. Meek did, however, reject Rod Stewart, apparently telling him: ‘You look fucking awful, you’re ugly, you’re short, you sound terrible – fuck off!’

Decades before Stock Aitken Waterman or Simon Cowell, Meek was making records with soap stars and television personalities, cutting discs with Jenny Moss from Coronation Street and, more successfully, the actor John Leyton. He sang the Meek-produced Goddard composition ‘Johnny Remember Me’ on Harpers West One, a show that attracted 25 million viewers. The record duly went to number one. David Bowie claimed never to have met Meek, though two groups he played with, the Konrads and the Riot Squad, certainly did. Yet Bowie’s first chart hit, ‘Space Oddity’, bore all the hallmarks of a Meek production circa ‘Telstar’. And Thatcher was right: ‘Telstar’ is a lovely song.

Comments