John Humphrys last night presented a documentary on welfare, the single most important

topic in Britain. It was excellent, and I’d recommend CoffeeHousers watch the whole thing (on iPlayer here). Humphrys is a great presenter, himself the product of the now-forgotten days of social

mobility when a kid from a working-class district (Splott in Cardiff) could end up presenting the 9 O’Clock News in his 30s. “In those days, everybody was expected to work,” he

said of his childhood. “We knew only one family where the father did not work, and he was a pariah…. Today, one in three of working-age people is on out-of-work benefits.” This

is what the welfare state has done to communities like his. But it’s a hideously complex problem, and one the documentary explores. Here’s my summary:

John Humphrys last night presented a documentary on welfare, the single most important

topic in Britain. It was excellent, and I’d recommend CoffeeHousers watch the whole thing (on iPlayer here). Humphrys is a great presenter, himself the product of the now-forgotten days of social

mobility when a kid from a working-class district (Splott in Cardiff) could end up presenting the 9 O’Clock News in his 30s. “In those days, everybody was expected to work,” he

said of his childhood. “We knew only one family where the father did not work, and he was a pariah…. Today, one in three of working-age people is on out-of-work benefits.” This

is what the welfare state has done to communities like his. But it’s a hideously complex problem, and one the documentary explores. Here’s my summary:

1. Work for £5.50 an hour? Humphrys calls in on Pat Dale, a single mother of seven children who hadn’t worked for 20 years. She told him: The reason I wouldn’t

work for the minimum wage is that, if I did, I’d get paid £ 5.50, I’d lose my rent benefits, I’d be working for nothing. ‘Would you work from 8 to 7 for £5 an

hour? I think that’d be disgusting.” Another guy, Steve, said he “could not afford minimum wage work.” If this were an American documentary (like the superlative Waiting for Superman) you’d have a cartoon at this point showing that Steve and Pat are right — totalling up what the

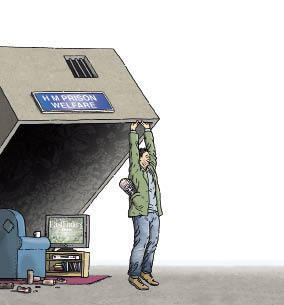

state gives you for having seven kids on the dole, and what you’d get from working. The system, not the people, is to blame.

2. Decommissioning humans. “Some of my friends have been on benefits all their life. They make a career out of not having a career,” one guy told Humphrys. Think about that: how should this even be possible? That’s how bad the system is, and it has entrapped the lives of millions in this country.

3. Middlesborough’s stolen workforce. Mayor Ray Mallon pointed out that 18,000 out of 88,000 in Middlesbrough are on out-of-work benefits. This is not much larger than the proportion nation-wide, but it was his explanation that struck me: “it’s almost a lack of hope, a lack of engagement. That the state have looked after us, and they’ll continue to do it.” He’s right: government is the problem, unreformed welfare is undermining family and communities every day. There is a huge sense of urgency here.

4. America the horrible. Humphrys interviewed Americans on the poverty line, always shocking to us Brits. People whose benefit runs out after a certain number of months, people who are given food stamps not cash. It’s not quite Britain’s alternative: the systems in Australia are closer to what Chris Grayling has in mind. But still Humphrys found consensus. “There’s a growing realisation that if you want a welfare benefit you have to work, one way or another, for it. And it’s that attitude that might be starting in Britain.”

5. The limits of health assessment. A woman was interviewed, who claimed that she could not work because she was fatigued. She had been hauled in by the authorities to check, and given a disability rating of zero. But she appealed, and was let off automatically. Watching her — articulate, presentable, likeable — I wondered, is she really economically useless? Is there no work she could do at all? And I also wondered if the appeals system is too easy, overturning decisions automatically. It is not, in my view, compassionate to let everyone with a CFS diagnosis on permanent, never-ending welfare. Unlike Rod, I do regard CFS as a proper medical condition — but its one people do learn to combine with work. Unemployment is self-reinforcing, and also breeds ill-health. A better approach is needed.

6. Intergenerational poverty. There was a heartbreaking scene at the end in which Humphrys visited City Gateway, a charity in Tower Hamlets where they had about two dozen teenagers who were trying to get on a placement. Humphrys asked how many of their parents were working now, only one put up their hand. One said of his father: “He don’t work, he never has worked. That’s his life preference, so if he wants how he wants to live his life then let him.” “They think training doesn’t get you somewhere,” another guy said of his parents. “But I told them: I wanna change my life.” As Humphrys said, it’s heartening that these kids who had such a bad start in life want to break into work. But they’re in the minority.

His conclusion was that the age of entitlement is drawing to a close, because the political class has decided it has to end. If only things were that simple. Welfare reform is the single toughest task in politics, because you can be so easily attacked for it. It’s a very unglamorous topic: when we put it on the cover of The Spectator we took a huge sales hit. The BBC giving this programme such a slot (9pm) was a great definition of public service. It’s a problem that can only be solved with cross-party consensus (as in America, where Clinton and Gingrich agreed). And it can only be solved if more people get angry about the harm that an unreformed welfare state is inflicting on our communities ever day.

Comments