Toby Litt begins the titles of his books with consecutive letters of the alphabet and takes delight in shifting style and genre. He has now reached J, and science fiction.

There has been a flurry recently of ‘literary’ writers trying their hands at SF. For the most part, the complaint raised against these efforts is that they may be better written than most of science fiction, but they aren’t much cop as science fiction. Anyway, science fiction need not be badly written: fans are fond of quoting Sturgeon’s Law (after the science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon) — ‘Ninety per cent of SF is crud, but then 90 per cent of everything is crud’.

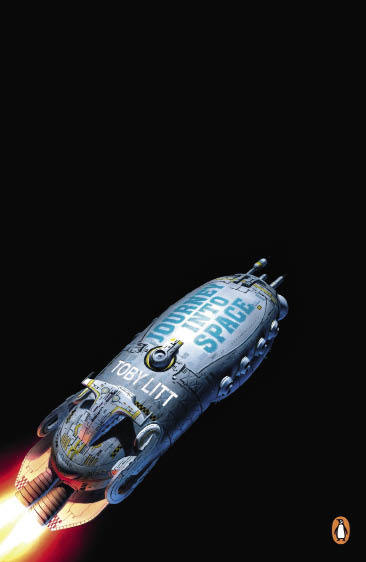

The corollary is that even the badly written stuff must offer something special to succeed. Usually that is novelty, and its absence is one reason why, for example, the SF sections of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas are a failure, and The Children of Men by P. D. James is inferior to Brian Aldiss’s Greybeard. But there are happy exceptions. Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go examines cloning, one of the hoariest of themes, but does so brilliantly; The Book of Dave, by Will Self, is deeply indebted to Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, but none the worse for that. Toby Litt has managed it too. He has done nothing very new, but he has written a good novel. Journey into Space avoids cliché, the sentences never go clunk, the reader is always engaged — and it offers a thoroughly old-fashioned future.

Litt sets his tale on a generation starship, once a familiar device in SF though it has been rather out of favour since the 1970s. The premise accepts the rules of physics and assumes that spaceships cannot travel faster than light — an obvious impediment in tales set in Outer Space.

Robert Heinlein was probably the first, in 1941, to explore the possibilities offered by generations of passengers and crew confined to the ship, gradually losing their memories of their point of origin and knowing that only their remote descendents will reach their destination. Sometimes, as in his Orphans of the Sky and Aldiss’s Non-Stop, perhaps the best-known and most successful of such stories, the occupants of the craft have lost all sense of their past and present circumstances.

Litt does not go quite that far, but he deftly presents the ease with which history may be forgotten, social mores changed out of all recognition, and religion mangled and reinvented.

He begins with August and Celeste, incestuous, doomed lovers who yearn for memories they have never had; their son, Orphan, becomes a kind of idiot Messiah, whose rule frighteningly demonstrates the fragility of civilisation. The carnage and collapse on the ship are mirrored, it turns out, back on Earth.

The moral is that human beings are certain, through their own stupidity, to lose and destroy everything they once valued, yet there is a note of hope, too, in the conclusion, which wrong-foots the reader, though in a satisfactory fashion.

In a recent interview Litt said: ‘Don’t write what you know. You don’t know what you know. Surprise yourself.’ It is a sentiment rather like L. P. Hartley’s declaration, that ‘It is safer for a novelist to choose as his subject something he feels about than something he knows about’. It is part of the appeal of science fiction and, oddly enough, the quotation that prefaces Non-Stop.

Litt knows how to do science fiction. Better, he knows how to tell a story.

Comments