Safari log: 3.56 p.m. and the Land Rover is parked up on the savannah. Inside, we wear dark glasses and muted clothes. Minutes pass and we still can’t spot the animal we have come to see. We are told that she only comes out at certain times of day, that she is shy.

No, we’re not actually in Africa; we’re in a prep school car park in the Home Counties, on what is known as an Ozempic safari. We have gathered to spot the ‘Mounjaro Mummies’ prowling around after the summer holidays. It’s wild, in all senses. It’s also socially and morally dubious.

Word on the street is that the number of Mounjaro Mummies has swelled after the two-month break, their transformations taking place away from the daily scrutiny of the school run. Given that we can’t get a proper look at them without being too obvious, we have come to operate a stake-out system.

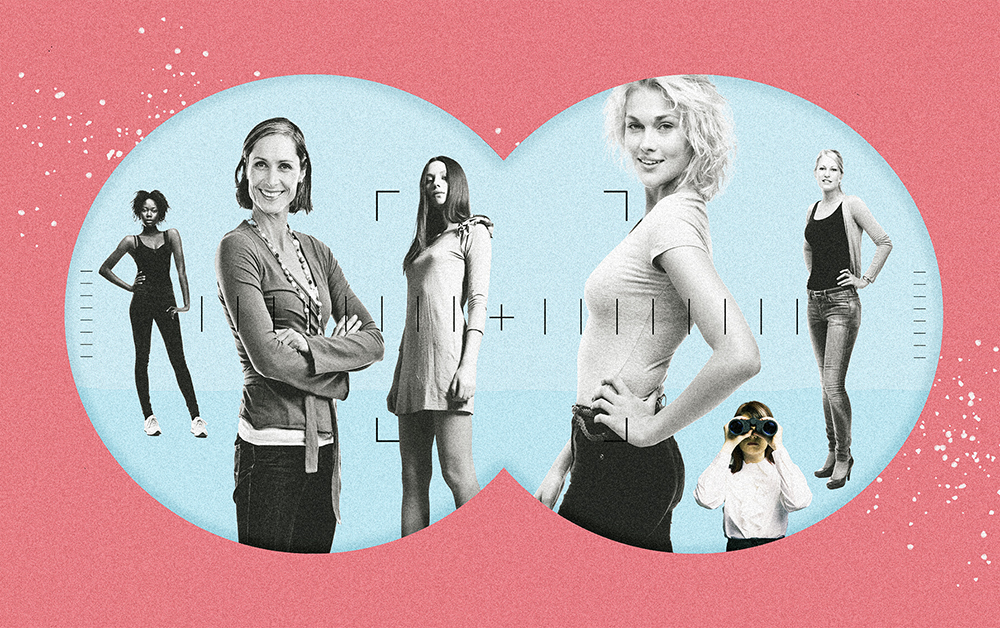

We know exactly what to look for: sunken faces, slightly wasted arms and, of course, dramatic, envy-inducing weight loss. I’m talking at least three dress sizes dropped and a slightly reptilian facial expression – the sort that Sharon Osbourne and Serena Williams now display. This is weight loss we all know can’t be achieved in two months by restricting your calorie intake and doing pilates. The ‘wellness’ jig is up: throw your Lululemon leggings away. Third-wave body positive feminism has lost. Really, we should stick a white flag on top of the Land Rover.

From the privacy of the car, the drumbeat is one of disapproval. ‘It’s extremely irresponsible as a mother,’ one of us says, adding: ‘These women would feel so much better if they did it the right and honest way.’ ‘I don’t want my children to see vanishing women, it’s impossible to explain to them,’ another says. ‘Fair enough if you’re obese or you have diabetes,’ I chip in, adjusting my Ray-Bans, ‘but this is recreational Ozempic use for the rich; body positivity is now only offered as a sop to those who can’t afford to be on the pen.’ Widespread nods.

Given that the price of Mounjaro has risen by 170 per cent in recent months, you need to be in a certain wealth bracket to afford it at all – not that it matters on our chosen safari plain. Estimates suggest that 1.5 million people in the UK are injecting weight-loss drugs, or GLP-1 agonists, with 90 per cent of these paying privately for the privilege. It is thought that more than half are using Mounjaro, soon to be the most expensive of all. The Waitrose classes – and that’s us – are prepared to pay.

Soon enough, upon spotting a woman in athleisure clothes and a baseball cap, we discuss what it means to be thin. We tiptoe around the idea that thinness, as a tenet of female socialisation that we millennial women grew up with, has always meant sacrifice. You can’t leapfrog dedication, discipline and pain, we seem to be saying. ‘I’ve never missed a day,’ one says, describing how she has exercised religiously all her life. I think of the time I nearly fainted from hunger on the District line as a dieting teenager. ‘Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels’ – until you collapse.

We know what to look for: sunken faces, slightly wasted arms and, of course, envy-inducing weight loss

The Republic of Skinny is a strange place. Most of its long-term residents want to credit their size to discipline and personal responsibility rather than genetic good fortune or, heaven forbid, wealth. But if thinness is available more easily, its social capital becomes devalued. What does it mean to be skinny if any old person can do it? Where do we stand now?

In the Republic of Skinny, something serious has happened and we all know it: the walls have crumbled, and a new structure has emerged. But the new structure looks flimsy and jerry-built to our eyes. In short, we think it is cheating; or as the critic Kat Rosenfield has put it, the ‘equivalent of buying indulgences instead of performing atonement’.

I look out of the window and see a woman I have long suspected to be on Ozempic, but her weight loss is too subtle for me to call it. I dimly remember that she didn’t eat any sandwiches under the gazebo on speech day.

Ozempic and other GLP-1 agonists that work by restricting appetite, or turning off the ‘food noise’, have begun a medical revolution. Curiously, though, we don’t talk enough about the social revolution they have engendered – the way in which they have affected how women look at other women.

Once, being fat meant moral decrepitude or a certain kind of laziness. Consider the old euphemisms – ‘she’s let herself go’ or ‘she’s chunked up a bit’.What if instead we saw metabolism and appetite as a peculiar nexus of biological facts, environmental forces and genetic tendencies rather than moral choices? What if we began to see the discovery of semaglutide as an unalloyed force for good? What if, indeed.

But I don’t see this intra-female empathetic turn whereby the use of weight-loss drugs is framed as a feminist choice to finally give women a break from the patriarchal tyranny of having to stay slim. Instead, I see women viewing each other with suspicion and derision. I see women hoarding frightful examples of liver failure, dysentery and – worst of all – weight regain as examples of the Faustian pact of ‘the skinny pen’.

Psychologists at the University of Melbourne, researching the psychosocial consequences of women undergoing plastic surgery, concluded that ‘perceptions of attractive women are worsened when these women decide to seek cosmetic surgery’. What will the study of the psychosocial effects of weight-loss drugs among women tell us, I wonder? I suspect it will read as an obituary for liberal feminism.

Safari log: 4.22 p.m. A hush descends in the car. We have spotted a real one. I can’t quite believe my eyes: she is not so much slimmed-down as an entirely different woman. Her jeans hang off her, her posture is different, her twig-like arms are shown off in a sleeveless Sézane top. I strain my eyes to get a look at her face but I’m too slow; she has darted off like a gazelle. Our assembled group is quiet. I probably shouldn’t, but I declare to the group that I think she looks amazing. Nobody says anything.

Henrietta Harding is a pseudonym.

Comments