Crisis relocation. A term from the Cold War. It means being somewhere else when it happens. When the threat of the Soviet Empire was as much a part of daily life as tea and toast, there were fixed plans to shift our leaders out of harm’s way at the whiff of the first missile.

Birds operate the same strategy. When the Cold War of winter strikes, many birds cope with the emergency by being somewhere else. So you’d think that this would leave the country a little depleted at this time of year: after all, the swifts and swallows are long gone and with them most of the warblers.

But that’s not the case at all. The same strategy of crisis relocation brings thousands of birds flocking into Britain to savour the balmy weather of our winters. Our bleak wind-scoured estuaries are Caribbean beaches for some birds, while our back gardens and parks are a second home in Tuscany for many more.

And if you want to give yourself a real birding treat, then spend the next few weeks haunting the supermarket car-park. For some reason these places are often planted with cotoneasters and other berry-laden bushes. When there’s an ultra-cold snap on the continent, a particularly dashing bird will come in gangs to feast on the berries.

These are waxwings, an irruptive species that loves to take birders by surprise. Suburban streets are another favourite habitat: anywhere there’s berries, but with a special taste for the mundane. They like the contrast, I suppose: they’re raffishly handsome things with tendency to overdo the eye make-up and the millinery.

This country is death to swallows in the cold weather, because there’s nothing to eat: the aerial plankton they feed on, the invertebrate life of the skies, simply doesn’t exist in winter. But Britain is life itself to Scandinavian thrushes and to the swans and geese of the Arctic.

My garden is currently full of blackbirds, and they’re all males: sleek, black and glossy with banana-yellow bills. Most of them have flown in from Scandinavia to feast on the fallen apples. Conditions are much harder in Scandinavia, and the days are much shorter, limiting foraging time.

It’s still sub-optimal in Britain, but they put up with it. The females fly much further south but the males can’t afford this luxury. They need to get back to the breeding-grounds at the first hint of spring, to grab the best territory, to hold on to it by means of song, threat and, when necessary, combat — and be all set when the females finally make it back. That’s the best way to become an ancestor: the tried and tested way of the centuries.

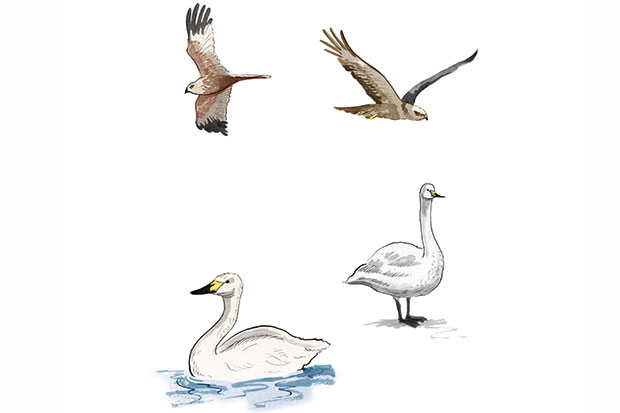

Meanwhile, at some places along the coast and some inland waterways, the wild swans fly in from the far north. These aren’t the mute swans of parks and ponds: these are whooper swans and Bewick’s swans that come here in bugling flocks, enormous and uncompromising.

They are there and can be enjoyed by everyone, particularly easily at the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trusts reserves at Slimbridge, Welney and Caerlaverock. But my favourite spot for winter spectacle is the Norfolk Wildlife Trust’s reserve at Hickling Broad.

Here it is possible to get in touch with Norfolk’s tiny population of cranes, which stand five foot tall and move with impossible grace. They’re here all the year round: a population that established itself naturally in the 1970s and decided that migration was the fool’s option.

You can also see marsh harriers in extraordinary numbers; I’ve seen 50 in an hour. These birds were down to one breeding pair in the 1970s. Now, thanks to good conservation, laws against pesticides and fewer gamekeepers, they’re back in numbers.

These birds always used to migrate to Africa for the winter: these days a lot of them don’t. That’s why this spectacular winter roost is very much a modern phenomenon. It seems that marsh harriers have changed their minds about the British winter.

They’re not alone. Many chiffchaffs and blackcaps now stay with us for the winter. So do little egrets, who a generation ago were mad exoticisms in Britain. Now they’re part of daily life. The breeding population of 1,400-odd birds is joined by birds that come here from the Continent: the wintering population is getting close to 5,000, a big step up from none.

The world is changing before our eyes. We don’t need figures and measurements to tell us this: the birds do that, being mobile and visible. They don’t so much tell us truth as flaunt it. There aren’t too many climate-change sceptics among the birds.

Crisis relocation is one of the strategies that makes the world go round. But perhaps the nature of the crisis is changing. Birding is always good, but it’s never an empty pleasure.

Comments