Last month’s terrorist attacks in Volgograd were doubtless an attempt to warn foreigners off the Winter Olympics in Sochi next month. An attempt, too, to remind Vladimir Putin that his problems in the Caucasus – many of them at least partially made in Moscow – haven’t gone away.

For understandable reasons the bombs have caused plenty of folk to wonder about the security of athletes and visitors in Sochi. Those concerns are, plainly, real even if we may also, I think, expect the Russian state to erect several rings of steel around the Black Sea resort.

The real concern, frankly, is that Russia was awarded the games in the first place. As I’ve written in today’s Scotsman:

The games should never have been sent to Russia in the first place. Not because of the threat posed by Islamist separatists but because of the character and record of Vladimir Putin.

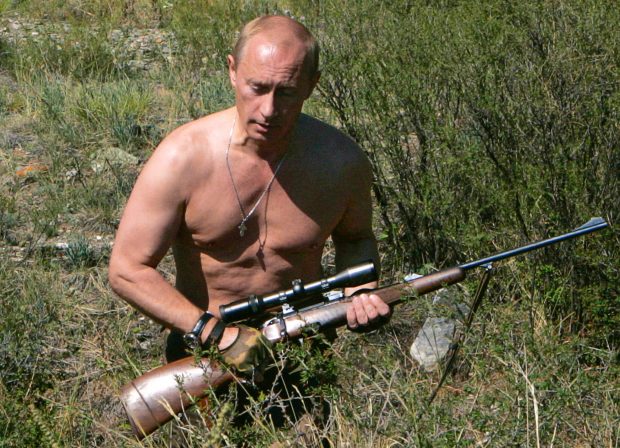

The Russian president has never hidden who he is. His character has always been on display to those who chose to see. In 2000, as he prepared for the elections that would confirm his status as Boris Yeltsin’s successor, Putin’s backers arranged for a hastily-written biography to be written to show off the new man’s credentials to a public that knew relatively little about the life and rise of this formerly obscure KGB colonel.

It contained this revealing exchange: “Why did you not get inducted into the Young Pioneers until sixth grade? Were things really so bad?” “Of course. I was no Pioneer; I was a hooligan.” “Are you putting on airs?” “You are trying to insult me. I was a real thug.”

This boastful Russian leopard has never changed his spots. Putin’s victory in 2000 was never in doubt. Even so, his allies went to extraordinary lengths to secure his victory. In the weeks before the election Russia was traumatised by a series of bombings targeting apartment buildings in Moscow and other Russian cities. In Moscow alone 224 people were killed in two bombings. The attacks were blamed on Chechens and used as a pretext for both a new Russian offensive in the Caucasus and tightened security in the rest of Russia.

In fact, there is ample evidence that the Moscow apartment bombings were planned and carried out by Putin’s former colleagues in the FSB (the KGB’s successor). It is almost inconceivable that Putin did not know about this. As soon as he was elected the bombings ceased.

The bombings were used to advance Putin’s political interests. In the climate of fear and hysteria dominating Russia then, anyone promising or projecting strength could have been elected. That man happened to be Vladimir Putin.

The essential character of Putin’s regime has never changed. It is a regime that has offered Russians security and certainty which, after the chaos and looting that marked the 1990s, has proved understandably appealing to many Russian citizens. Nevertheless, his regime has never declined the opportunity to heighten those fears and use those fears ruthlessly.

There is, again, ample evidence that the Russian security services knew about, and did nothing to stop, the 2002 siege at a Moscow theatre that ended with the deaths of 129 people and, two years later, the hostage crisis at a school in the North Ossettian town of Beslan that ended with 312 deaths. In each instance these acts of terrorism were exploited by the president to justify both Russia’s wars in the Caucasus and Putin’s increased grip on power in Moscow. These deaths were useful deaths.

Putin’s claim this month that, unlike terrorists, “Russian special units always do their utmost in the course of special operations to protect civilians, women and children” would be laughable if it weren’t also sickening.

The recent release of political prisoners, including the oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and members of the dissident punk band Pussy Riot will only fool gullible foreigners. These releases may be welcome; they are also a sop to international opinion that does nothing to alter the fundamental nature of a Russian regime that is, at best, a kind of twilight democracy.

Dissent, as the graves of the journalist Anna Politkovskaya and the former KGB officer Alexander Litvinenko remind us, is dangerous in modern Russia. Politkovskaya and Litvinenko are far from the only regime opponents to have died in mysterious circumstances. The chief suspect in Litvinenko’s death from polonium poisoning, Andrei Lugavoy, was made a member of parliament and thus granted immunity from prosecution – including any attempt by Britain to have him extradited.

As the writer Masha Gessen has observed: “The simple and evident truth is that Putin’s Russia is a country where political rivals and vocal critics are often killed, and at least sometimes the order comes directly from the president’s office.”

Whole thing here. Security issues are the least of the problems with modern Russia.

Comments