Gabriel Weston is an extraordinary writer. An ENT surgeon who now prefers to carry out excisions of skin cancers, she has found a niche in exploring moral dilemmas in medicine. Her first book, Direct Red (2009), examined such clashes as a patient’s need for empathy and a surgeon’s requirement to be steely. A serious problem at the time was how the punishing schedules of junior doctors made it virtually impossible for them to give patients the attention and compassion they so often needed.

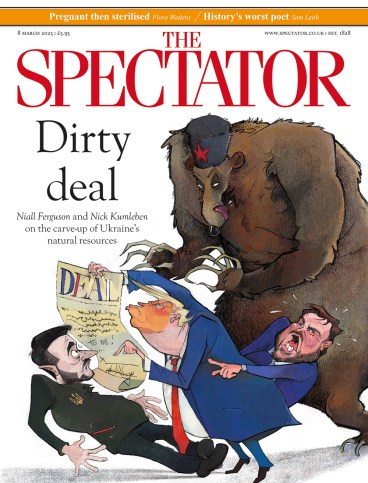

Weston’s second book, Dirty Work (2013), was a novel – and no less ethically probing. Nancy, its female gynaecologist protagonist, takes on her department’s unpopular abortion lists, telling herself she is performing an essential feminist service. The reader soon becomes aware of how complex the issue is. I knew this well myself, having had to anaesthetise a very young woman under-going her seventh abortion. As someone who longed for babies, I felt sick, and subsequently gave up my gynaecology list. In the novel, Nancy freezes one day in surgery when the mother bleeds, and finds herself charged with professional misconduct. Both books deal in a thrilling, nuanced, illuminating way with medical ethical dilemmas.

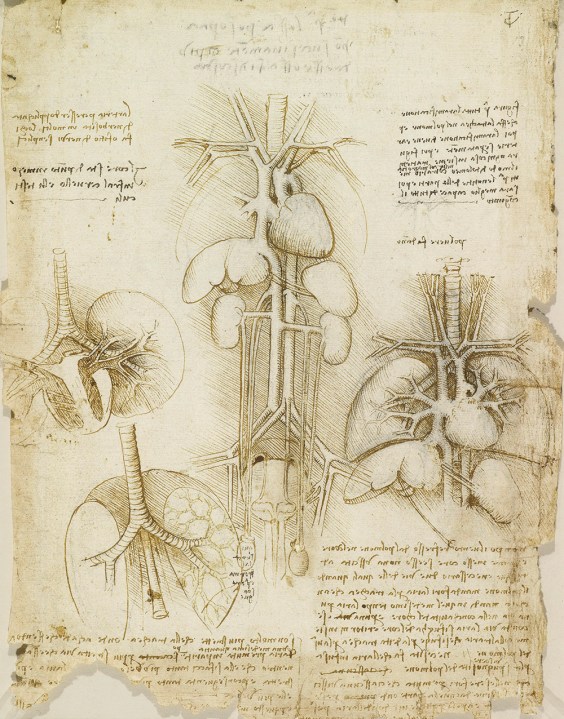

Now Weston turns to the wonder of the human body. Alive is a guide to our organs: their anatomy, and how and why they function. It is interspersed with details of Weston’s life – her personal experience of illness; and how, as an English literature graduate, she came to study medicine. (One day she found refuge from an unhappy relationship in the peace of her GP’s consulting room. It happened to coincide with an innovative drive by a medical school to recruit arts graduates.)

I love Weston’s writing – but having ploughed through anatomy at medical school, followed by two different postgraduate degrees and all the related exams, I found my enthusiasm for the subject waning. However, Weston does bring the research on anatomy right up to date. In her chapter on the gut, she cites the latest findings on the gut biome and its importance in health, as well as the link between the brain and the intestines and their resident bacteria.

In her section on the genitals, she excoriates men who have ignored the importance of the clitoris. She points out that, developmentally, the clitoris is very similar, structurally, to the penis, so it should be no surprise that the two are analogous as the seat of sensory pleasure. She might perhaps have highlighted the disparity in the past century between the medical focus on the vagina as the only significant female sex organ and the feminist literature of the time – which was screaming about the clitoris from the 1960s on.

Moral problems, as in the previous books, are addressed. In the chapter on the lungs, there is a sense of outrage. Weston mentions migrants suffocating in lorries; drowned infants washed ashore in the Mediterranean; George Floyd stifled. But these are touched on, rather than explored, so there is no real consideration of the complexities of migrants travelling illegally, parents endangering their babies’ lives or people-traffickers profiting at the expense of their vulnerable clients.

Still, the book is a powerful read. Weston attends a liver transplant and a heart transplant, as well as visiting a dialysis unit and watching numerous other operations. Her descriptions, you might say, really make the human body come alive.

Comments