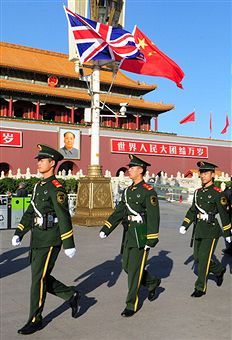

The world is undergoing a permanent shift of power from West to East, with China being

the biggest beneficiary and middling states (like Britain) likely to be the biggest losers.

The world is undergoing a permanent shift of power from West to East, with China being

the biggest beneficiary and middling states (like Britain) likely to be the biggest losers.

The government may, in the words of William Hague, reject any kind of strategic shrinkage. But if China’s economy continues to grow at even half the rate it has developed until now, Britain will end up looking small no matter what policy it pursues.

What is the best way to deal with a country like China, which on current projections, will have a larger economy than the United States by 2050? How best to position Britain if the US and China abandon peaceful co-existence, and, as the FT’s globe-trotter Gideon Rahman predicts in his new book Zero-Sum World, begin to fight?

The first is to engage at high levels, and in a respectful but also determined manner. As long as David Cameron learns from his past mistakes (in other words: no lecturing China while visiting one of China’s neighbours) this should be easy. The PM, unlike his predecessor, is good at building the personal relationships while putting his priorities across.

The second is to co-ordinate, as best as possible, with France, Germany and Britain’s other allies. China tries to pry Western governments apart, bullying them one by one. It is happening again in the run-up to the Nobel Prize ceremony and will happen every time the Dalai Lama books a trip.

It will not always be possible to maintain a common stance – Germany’s export-led strategy and the USA’s current account deficit puts these countries in a different position vis-a-vis China than Britain. But nothing pleases Beijing more than when European countries under-cut each other. Market access is something everyone can agree on; so is the demand that China’s currency is freely convertible.

Third, Britain needs to look beyond China and help its European allies do the same. The early trip to India was a great move, but it also means working with other ASEAN countries; they too represent opportunities for growth, which, if exploited will temper China’s rise. China-watcher Jonas Parello-Plesner has argued for a “KIA” policy – for Korea, Indonesia and Australia. A visit by Nick Clegg to these countries early in the New Year would be wise. European absence from the East Asia Summit in Hanoi needs to be rectified.

Fourth, Britain needs to find common projects with China. Unlike Labour’s approach, the Government must not lecture China to behave better in Africa.

But there should be scope for cooperation – on issues like energy security, climate change and how to develop the kind of governance that both China and Britain need in places like Congo, Angola

and the SAHEL.

The Prime Minister will come back from China to a smaller country than he one left behind – at least that is how most Western leaders have felt after trips to China. Even the US President looked small and in awe during his visit. But a pragmatic China policy can preserve Britain’s eminence at least a while longer.

Comments