Young people are supposed to drink a ton, have a lot of sex, hang out with their friends at every opportunity and vote for the left. Today’s young don’t live up to the stereotype. According to polls, they are one of the most responsible generations on record. Across the West, the share of young adults who binge-drink or who are sexually active has fallen to a new low. Teenagers spend far less time hanging out with their friends than their parents or grandparents did. They even seem to be defying political expectations – though their recent drift to the right has, in its own way, succeeded just as well in horrifying their elders.

Last month, for example, a group of fashionably clad vacationers at an upscale bar on the German island of Sylt shocked the country by singing along to an old tune by DJ Gigi D’Agostino with new lyrics: ‘Ausländer Raus’ (‘Throw out the Foreigners’). After going viral, the song has done the rounds. Young Polish and Austrian fans united to sing the slogan before a recent match at the Euros. Some of this is a form of trolling and, at times, linguistic incomprehension. Last week, the German police, who have absurdly treated such incidents as a criminal matter, went to interview one set of alleged malefactors, only to find they were Eastern Europeans who didn’t speak enough German to understand the words. But while the significance of viral trends shouldn’t be overstated, electoral results show the drift to the right may be all too real.

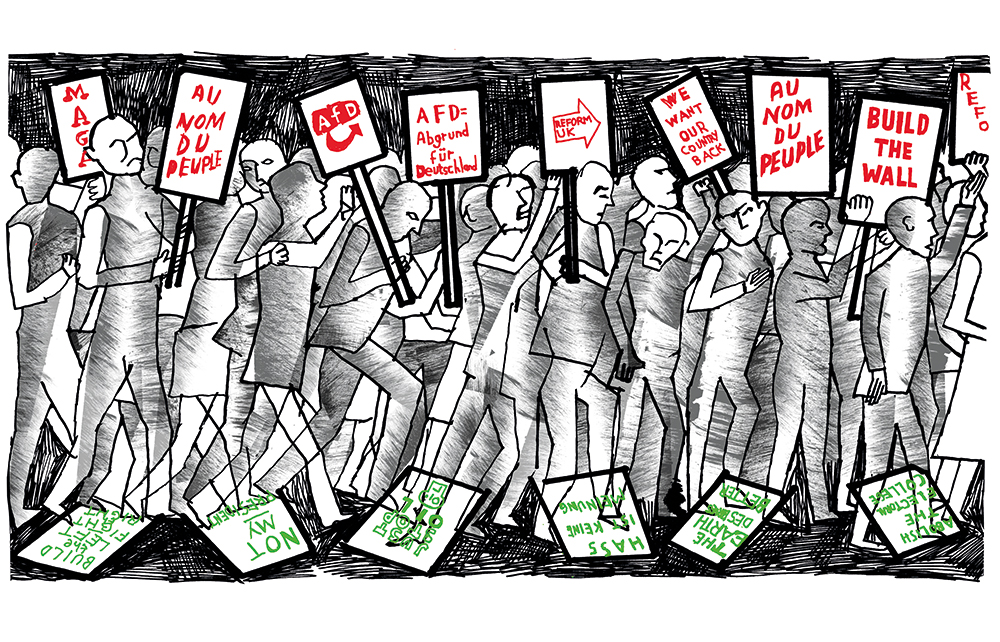

Left-wing parties in Germany championed lowering the voting age because they expected to benefit

This year, 16- and 17-year-olds in Germany were allowed to vote for the first time in elections to the European parliament. Left-wing parties from the Greens to the Social Democrats championed lowering the voting age because they expected to benefit. The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) unsuccessfully sued against the change because it expected to suffer. Both sides proved to be wrong. In 2019, young voters in Germany leaned left, favouring the Greens over the AfD by a 5-1 margin. This year, they swung to the right: more young voters supported the AfD than the Greens.

To be sure, the far right increased its share of the vote across all age groups. But the change was most dramatic among the youngest cohorts. While the AfD improved its results among the over-seventies by one percentage point, its share of the vote among the under-25s rose by 11 percentage points.

Germany is no outlier. In France, youth support for Marine Le Pen’s National Rally has increased by a similar margin. The movement was the top choice among voters below 30. The trend is likely to continue in the snap election called by Emmanuel Macron, which will give the party’s young leader, Jordan Bardella, 28, a real shot at becoming the next prime minister.

Polls suggest the New Popular Front, an alliance that includes parties from the far-left France Unbowed to the centre-left Socialist party, will edge out the National Rally among voters below 25. But the far right is dominant among those between 26 and 35, with nearly four in ten supporting Le Pen and Bardella; it’s voters who have reached retirement age, not those just starting work, who are least likely to vote for them.

For now, a more classic generational divide persists across much of the Anglophone world. In Britain, many young voters appear desperate to vote out a dysfunctional government after 14 years, with Labour polling at close to 50 per cent among the under-25s. But here too, the devil is in the detail: the same poll shows more than 20 per cent of young Britons support Reform.

Over in America, young voters are not nearly as left-leaning as the country’s media and political class have long assumed. Asked about their political orientation in a recent poll, 36 per cent of young Americans called themselves liberal, 33 per cent conservative and 31 per cent moderate. And while young Americans don’t appear to have any special love for Donald Trump, they are equally critical of Joe Biden. According to a New York Times poll of six key battleground states, Trump leads Biden among voters below the age of 30; it’s only among voters older than 64 that Biden has the edge.

Commentators have adduced a hodgepodge of explanations for why some young voters are turning right. There have been claims that young people are more politically ignorant, making them susceptible to misinformation. There have been endless articles claiming populists have some magical advantage on social media, giving them far greater reach on TikTok and Instagram (journalists have been covering the online antics of politicians like Bardella as if they are anthropologists who have discovered an uncontacted tribe capable of levitation). There’s also the argument that young people face unique economic struggles, making them more likely to rebel against mainstream parties. The rightward shift, however, is too recent for conclusions to be confidently drawn. For now, we’re in the realm of hypotheses. Some that have been advanced may eventually prove right. But it seems that, based on what we know, a different set of explanations should be considered.

The first point to understand is this trend is less surprising than meets the eye. Age is one of many demographic characteristics. While electorates have, at times, been polarised along generational lines, there have been far more contexts in which other demographic characteristics, from social class to ethnicity, were the most powerful predictors of political behaviour. The idea that the young always skew left is a myth. A simple piece of logic drives this point home. In the UK and the US, the left has been staking its hopes on the supposedly progressive preferences of young voters since the 1960s. Yet it has failed to win durable majorities on either side of the Atlantic in the decades these generations took to reach middle age.

This shouldn’t come as a shock. The radical political activists who draw the most media attention – whether hippies burning US flags in the 1960s or environmentalists throwing orange cornflour at Stonehenge today – are rarely representative of broader public opinion, even among their peers. When a larger cohort of young people skew left on an issue, as in the fight for greater acceptance for homosexuality, their favoured causes often enter the political mainstream, ceasing to divide left from right. And when it comes to other issues, such as taxation and the value of social order, young people tend to grow more conservative as they enter the workplace, get married and have children.

The radical activists who draw the most media attention are rarely representative of the peers

Young voters in Germany and France backing far-right parties to roughly the same degree as older voters are, then, much less unusual than widely assumed. Their voting behaviour is broadly in line with other age cohorts, as has often been the case – because young people face many of the same challenges as older ones. Insofar as young voters are motivated by the economy, for instance, issue polls and focus groups indicate they are less exercised by generation-specific concerns such as student debt than by worries shared across generations, like inflation. Asked to rank 15 issue areas by importance in one recent poll, Americans under 30 placed student debt at the bottom; the top three were inflation, the cost of healthcare and the price of housing. (Israel-Palestine, another topic the young are supposedly obsessed with, came second to last.)

In other words, a large part of the reason why so many young people vote for parties like the AfD or the National Rally is simply that the electorate as a whole has shifted to the right. Yet some generational experience clearly plays a role as well. To make sense of why the move towards the far right has been especially pronounced among younger voters (albeit from a lower base), we need to be more specific. The question isn’t ‘How come young people vote for the far right at all?’ but ‘What has happened in the last five or ten years that made them more likely to?’ Two possible hypotheses, the first more pertinent in continental Europe, the second in Anglophone countries, have been widely overlooked.

Polls indicate that young people in Europe are, for the most part, tolerant. Notably, they have higher levels of acceptance for ethnic and sexual minorities than their elders. To them, the idea of living in a diverse society is a concrete reality, not an abstract ideal. At the same time, they have experienced the impact of migration much more directly. Older people might encounter refugees or undocumented immigrants from a distance in shops or on public transport. Young people share classrooms and playgrounds with them for large parts of their days.

While there’s little indication that their proximity to immigrants has turned young people into racists, it has given them a front-row view of the challenges and, yes, the failures of integration. It is they who witness the problem of teaching newcomers French, German or English when they have a large group of friends who share their native tongue; the difficulty of keeping them on track academically when their parents have only an elementary school education; the clash of values when a significant proportion of students believe girls should abide by the restrictive rules of their ancestral societies.

Take Theodor, a 20-year-old from Berlin who went to the polls for the first time just after a terrorist attack in Mannheim, where an Islamist who’d come to Germany as a teenage refugee from Afghanistan attacked right-wing protestors with a knife, killing a policeman who intervened. ‘I am not against migration. Xenophobic slogans are disgusting, and we need more immigrants to come here for work,’ Theodor told Der Spiegel. Yet he worries that leftist parties are ‘blind’ when it comes to issues of integrating refugees and illegal immigrants. In the end, he said: ‘The attack in Mannheim was decisive for me. I voted for the AfD as a protest against our current policies on migration.’

Proximity to immigrants has given young people a front-row view of the challenges of integration

Experiences and interpretations vary among the young, as they do among the old. Many young voters attended schools where these problems were less pronounced, or ended up forging close friendships with the children of refugees. And of course most young people across Europe didn’t vote for the far right in any case. But it’s perhaps unsurprising if it turns out that a portion of them in France and Germany have been radicalised by seeing the challenges of integration for themselves. What’s needed to change their mind, as Theodor’s testimony suggests, aren’t some magical talking points advanced by a TikTok influencer, but credible solutions to real problems.

The second hypothesis is linked to the rising obsession with group identity, and the first indications of a rebellion against it among the youngest cohort. Especially in the US, what I have called the ‘identity synthesis’ now structures many schools’ teaching practices, with some students taught, implicitly or explicitly, that their moral status depends as much on the group into which they were born as on their individual actions, achievements or aspirations. And even as membership of the ‘wrong’ group has come to render someone morally suspect, the list of ‘wrong’ groups has kept on growing.

A few decades ago, this list was mostly limited to white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, the so-called Wasps. Then it expanded to all white, straight men. Now, it increasingly comprises religious minorities such as Jews (said to be ‘white’), ethnic minorities such as Asians (said to be ‘white-adjacent’), and sexual minorities such as gay men (especially when, like the US politician Pete Buttigieg during the 2020 primary campaign, they are suspected of being insufficiently ‘queer’).

Many young people take this worldview for granted. It has, in record speed, gone from the rebellious creed of a small set of ‘social justice warriors’ to the received wisdom widely taught in educational institutions. These institutions assume it’s natural for students to feel most safe or comfortable in segregated ‘affinity groups’ or to worry about the harmful impacts of the forms of cultural exchange that they have learned to pathologise under the banner of ‘cultural appropriation’. But other students, perhaps no less numerous, are starting to reject such values. They sense the hypocrisies and ideological inconsistencies of their teachers, and are sick of being encouraged to see themselves in tribal terms.

The rejection of ‘wokeness’ is in danger of turning some young people into straight-up reactionaries. Some worship misogynists, such as Andrew Tate. Others turn the identitarian thinking into which they have been initiated from an early age against minority groups that are genuinely vulnerable. But at least as many of them merely seem to want an alternative to the calcified verbal formulas and peculiar moral categories that animate the discourse of established institutions and the electoral pitch of many Democrats.

A majority of young Americans consider themselves moderate or conservative and won’t vote for Biden in November. Only a small portion are chronically online to the extent that they’d be inclined to fulminate against the latest woke outrage. Yet it is, in part, the pervasiveness of woke ideas which has given many of them the impression that the left is unbearably preachy and altogether out of touch with their interests.

One indication of the electoral impact of these ideological transformations lies in a fast-growing gender divide. Whereas young women in America skew left, young men are increasingly drifting to the right. Two decades ago, both groups were similarly likely to say they lean left. Today, there’s a 40-point gap between liberal and conservative women, while men are only marginally more likely to be liberal than conservative.

Interestingly, this reaction seems to be as widespread among groups that have historically been counted among the victimised minorities. Biden’s share of the vote has held up reasonably well among older white Americans, who support him at similar levels as they did in 2020. Among young and non-white Americans, his share is rapidly declining, thanks in large part to this gender divide. According to some polls, young Latino voters are likely to back Trump come November. And although young black voters support Biden, their support has fallen markedly: while black voters below the age of 50 preferred Biden by a whopping 80 point margin in 2020, his advantage has dropped to 37 points. For the past 20 years, many Democratic strategists counted on a supposedly inevitable ‘demographic majority’; now, led by young black and Latino men, it may be so-called ‘people of colour’ who will give Trump the decisive boost.

The rejection of ‘wokeness’ is in danger of turning some young people into straight-up reactionaries

Perhaps the young black and Latino men turning towards him in especially high numbers want to be celebrated for their achievements, not pitied as perennial victims. Perhaps they’re angry at being lumped into the group of putative oppressors on account of their maleness, ‘cis-gender identity’ or ‘white-adjacency’ in one school assembly too many. Or perhaps they simply view the identitarian language of their teachers and many of their representatives as a pointless distraction from the bread-and-butter issues, like inflation, that they really care about. In any case, the racial arithmetic on which Democrats once counted to secure their electoral victories is breaking down fast; attempts to ‘rally the base’ by moving to the left are likely to backfire as most of the young and non-white voters who are abandoning Biden situate themselves to his right.

In Germany, members of the far right are sometimes called Ewiggestrige, literally those who are ‘forever of yesterday’. This phrase had some descriptive validity in the early years of the Federal Republic, when it referred to that dwindling cohort of Germans who remained nostalgic for the Third Reich. Today, the term – and the deeper assumptions to which it gives voice well beyond Germany – has become an empty incantation in danger of distorting reality. There’s no iron law by which the young will be more progressive or politically moderate than the old. Those who assume there is will badly fail to understand this political moment.

The great majority of young people in both America and western Europe are instinctively tolerant. But they have justifiable reasons to feel that their elders have created serious problems, from unaffordable housing to uncontrolled national borders, which those elders remain unwilling to face or remedy. Many of the young are therefore lending their support to political forces that are experts at tapping such grievances – however unlikely they may be to solve them.

Watch more on Spectator TV:

Comments