In 1959, Edvard Munch’s ‘The Scream’ was hanging above the bed where Francis Bacon nursed a fractured skull after falling downstairs drunk at his framer Alfred Hecht’s house on the King’s Road. It was there to be re-framed – a circumstantial detail Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan report neutrally, en passant, in their 2021 biography Francis Bacon: Revelations. An inadvertent cry, nay a scream, for attention? Or a frame-up? It was a decade after Bacon painted his first screaming pope, a palimpsest obviously based on Velázquez but equally in hock to Munch.

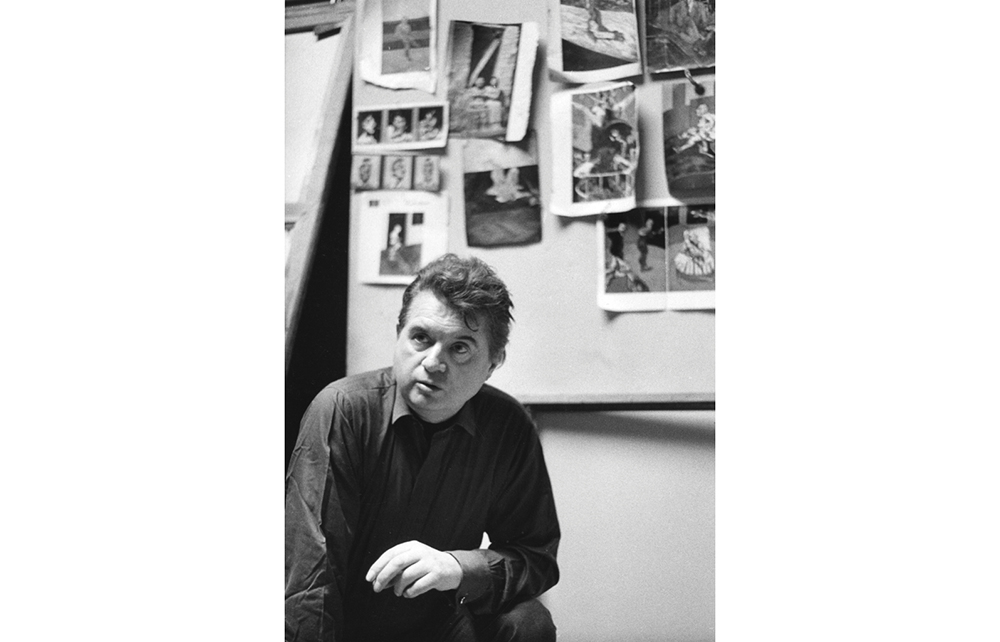

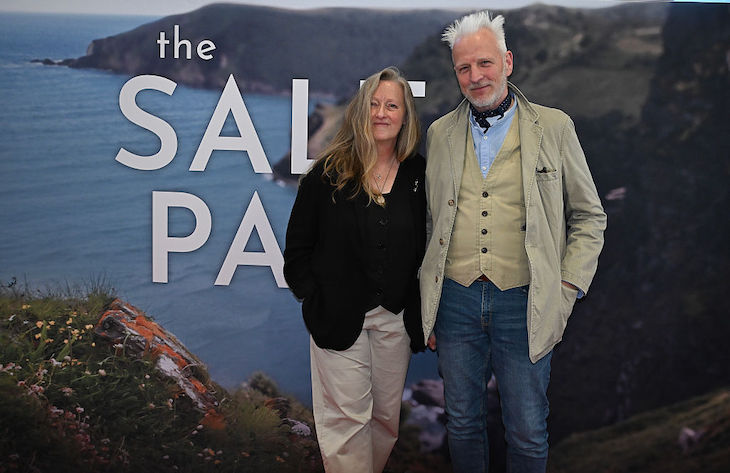

Francis Bacon: A Self-Portrait in Words is an annotated compilation by Michael Peppiatt of statements, letters, studio notes and selected interviews. You might think that the project is sabotaged by the artist himself on page 58: ‘One can’t really talk about painting, only around it. After all, if you could explain it, why would you bother to do it?’ It’s a decrepit truism which has been doing the rounds since the invention of the easel. On the same page, another ancient saccharine cliché: ‘I think one thing about artists – there are very few real artists, of course – is that they remain much more constant to their childhood situations.’ Picasso, typically intelligent and subversive, injected some counter-intuitive mischief into the tired idea that the artist uniquely remains in touch with his young self. As a child, Picasso said, he drew like Raphael, and it took him a lifetime to learn to draw like children. Compare this with Bacon’s fatigued evocation of childhood, hoarse with repetition, a whisper expiring as it is enunciated.

Bacon had no time for late

Picasso. He thought ‘Guernica’ ‘just a long story… an illustration’

And then you remember his childhood situation. Caught wearing his mother’s underwear, Bacon was handed over by his father to the grooms, who took him to the stables where he was beaten and sodomised. Which led to a lifetime of extreme, masochistic homosexuality: ‘The fishnets are a terrific success.’ Or: ‘Tell Arthur [Jeffress, financial backer of the Hanover Gallery] the Rhodesian Police are completely Him too sexy for words starched shorts and highly polished leggings.’ Or this typically unpunctuated epistle: ‘Charlie is a really handsome East End thug and would not be hard to make as he likes giving the whip.’ When Bacon left home, his nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, lived with him until her death in 1951, aged 80, permanently, if obliquely, locking him into his childhood situation. Those grooms explain, you might infer, quite a lot, if not everything. Think of all those screaming mouths and the way Bacon eroticised them, wanting to paint them as Monet painted a sunset.

On the other hand, you may think of Munch’s ‘The Scream’. Bacon’s lift was a heist so transparent that it is never once mentioned in these talkative, repetitive pages. Munch, as far as I know, merits only one dismissive mention, recorded by David Sylvester in the third of his interviews with Bacon: ‘But I’m not really saying anything, because I’m probably much more concerned with the aesthetic qualities of a work than, perhaps, Munch was. But I’ve no idea what any artist is trying to say, except the most banal artists.’ Munch on message. Munch on speakerphone.

Like many autodidacts, Bacon was anxious to advertise his highbrow credentials: Aeschylus’s Oresteia, T.S. Eliot’s poetry and prose, W.B. Yeats, Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Nietzsche. There is frequent, nervously habitual recourse to this narrow pantheon of greats. Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ – ‘It is impossible to say just what I mean! /But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen’ – supplies a reiterated, indebted Bacon adage: ‘Painting is the pattern of one’s own nervous system being projected on to the canvas.’ Not so different from the ‘rationale’, the theory behind Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, as once explained to me by Philip Rylands, the former director of the Guggenheim in Venice – viz. direct access to the painter’s essential self. A convenient, grandiose and unfalsifiable assertion. Bacon despised Pollock and the abstract expressionists as essentially decorative – ‘like old lace’, in Pollock’s case.

There were plenty of artists the waspish Bacon swatted. ‘I have never liked Hockney’s very sub-Picasso drawings, or any of his work for that matter. I suppose because it is so thin and bland that it is so popular.’ After generously recommending Lucian Freud to Norman Reid, the director of the Tate, he later withdrew his endorsement when Freud’s show at the Musée nationale d’art moderne in Paris had a great success: ‘I was myself very disappointed in his new style. It is a mixture of Frank Auerbach and a painter who used to show at Helen Lessore called John Bratby.’ Bratby. Oof. Jealousy.

Bacon also turned against Graham Sutherland, who had helped him climb the ladder. Peppiatt reports that he compared Sutherland’s portraits to the covers of Time magazine – a standard insult of the time if you were a realist figurative painter. John Berger said the same of Freud’s portraits in a New Statesman review. Bacon had no time for late Picasso. He thought ‘Guernica’ ‘just a long story…an illustration’. Positive verdicts? He praised Giacometti as a great draughtsman, Warhol’s electric chairs and car crashes and Damien Hirst’s flyblown ‘A Thousand Years’.

Here, though, Bacon is keener to claim kin with Velázquez, an undisputed great to set alongside Eliot, Aeschylus, Yeats and Conrad. His comments subtly seek to align Velázquez’s portraiture with his own:

I think Velázquez was very, very extraordinary, because if you analyse the heads of Philip IV and people like that you will see that these are profound distortions. But they are distortions which distort themselves into fact.

You see where this is going. Bacon is attempting to refashion Velázquez in his image, to place himself in a tradition, in a pantheon. Philip IV’s protrusive Bourbon lower lip, and a jaw like George Eliot’s, are mildly grotesque but hardly a Bacon face that’s been in the blender.

This is part of the careerism on show here. (Or legitimate career management, if you want to be kind.) By the end, one is weary of the endless toadying. Bacon loathed Henry Moore, but Peppiatt reproduces an incriminating congratulatory telegram celebrating Moore’s British Council show at Florence’s Forte di Belvedere in 1972. Bacon flatters and gives paintings to critics who further his career by prefaces, articles and introductions. To Michel Leiris, an important and assiduous advocate, painted twice by Bacon, he says: ‘I know that I am very privileged that the greatest writer of our time has written texts about me.’ Leiris is given a study of Isabel Rawsthorne. David Sylvester is given ‘Sleeping Figure’ (1974). Bacon painted Jacques Dupin. Edward Quinn, and Robert and Lisa Sainsbury of the Sainsbury Centre are given pictures. To Gaëton Picon, director-general of arts and letters when André Malraux was minister of culture in France, Bacon writes: ‘I am trying to do a painting to give you as thanks for all that you have done for me.’

At the same time, Bacon was suppressing writing he disagreed with, that didn’t follow the party line, or was indiscreet. An article by Peppiatt is stopped: ‘I do hope it will not be published in my lifetime also it is not at all accurate.’ And a piece by Eddy Batache is rejected: ‘It will not do as it is.’ Hugh M. Davies is encouraged and allowed to publish several articles, only to be later disappointed: ‘Since reading your manuscript what you have written has nothing to do with what I think about painting – I regret I don’t agree to it being published.’

In the interview section, Peppiatt doesn’t include the famous, influential interviews with Sylvester, nor a BBC interview with Richard Cork. Cork looked round the studio and said: ‘No drawings, Francis.’ Bacon replied with supreme self-confidence: ‘That’s because I can’t draw.’ There is a very winning side to Bacon’s personality when he turns his ready contempt on himself: ‘I don’t think that any of these things I’ve done from other paintings have ever worked.’ He told Sylvester his variants on Velázquez were ‘very silly’. Again: ‘There are an awful lot of my paintings I just don’t like at all.’ This is a much more convincing proof of Bacon’s artistic stature than the metaphysical megaphone, Thought for the Day pronouncements: ‘Man is haunted by the mystery of his existence.’

Comments