Letter home from prep-school boy, c. 1949: ‘Dear Mummy and Daddy, last night was the school play. It was Hamlet. A lot of the parents had seen it before, but they laughed all the same.’

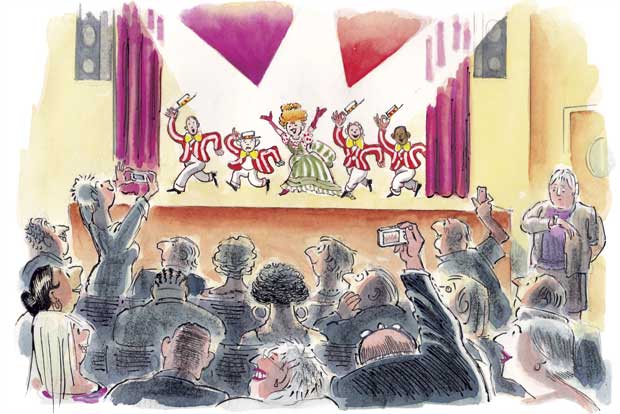

Guffaws from the audience at lines that are not supposed to be funny; total absence of laughter at lines that are: these are what actors and directors dread. The world of prep-school drama has come a long way since 1949. The three-hour Shakespeare tragedy marathon has generally been ditched in favour of swiftness and inclusivity. Under an hour is the preferred length, and it is not done to have lengthy black-outs while scenery is changed. Props have been simplified: one armchair is shorthand for a drawing room, one hay bale for a barn, one front door for a house. Each year, wisdom is passed from director to director. Here, gathered from some of the top prep-school play directors and writers — and some observant parents — is up-to-date advice for the coming year.

All agree that putting on plays is wholly good for children, the highlight of the school year, marvellous for team-building and confidence and broadening the vocabulary and imagination, and the key advice is: don’t underestimate what children aged between seven and 13 are capable of. ‘The children love it, and there’s always someone who surprises you by shining out with his or her brilliant acting,’ says Lucie Moore, the headmistress of Cameron House. If you look at the website of Eagle House school (renowned for its drama) you’ll see a moody-looking 12-year-old Macbeth standing in front of a brick wall (the gym?), and two 12-year-olds gazing into each other’s eyes as Romeo and Juliet. Does Shakespeare really work for this age group, I asked the head of drama Matthew Edwards. Absolutely, he said, provided you do an adapted and shortened version. ‘Our 12-year-old Romeo and Juliet were just amazing — even the tender moment when they first meet and have to kiss each other was so moving.’

Choice of play: Nick Morell, who directed an exuberant 101 Dalmatians for St Philip’s School in March, and is now writing his own West End musical called Del Sol (set on the Costa), advises: ‘For a whole-school play, you need something with enough lead parts for the children who will rise up to that, but you also need a play that can accommodate as many children as would like to be in it.’ Joseph, The Jungle Book, Bugsy Malone: these are ideal. ‘You need a quick hook — primary-colour good and evil, and the opportunity for quick-flash choruses.’ By writing the play (and many of the fizzing songs) himself, Morell makes sure that 75 per cent of the cast have a line of their own: a moment (however brief) to take the stage, which means a huge amount to them.

Tapping into children’s boundless energy and inventiveness: that is what you need to do, says Morell. ‘Prep-school children have a remarkable elasticity and inner energy. You see a boy hobbling in from the rugger pitch, covered in mud — and able to turn straight into Cruella de Vil. The trick is engaging with them, getting them back into the world you’ve been creating.’

How many hours of rehearsal do you need? It’s important to get the balance right, my interviewees said. ‘I’ve been to plays where they’ve tried to be too professional,’ says Nick Morell. ‘The children are clearly not enjoying it. They’ve had it rehearsed out of them.’ But Matthew Edwards at Eagle House says, ‘Try to do it as properly as possible: spend time getting it right. “Just one more time!” That’s my mantra.’ Damaris Lockwood (who has directed many prep-school plays) has calculated that 98 hours of rehearsal are needed to get a school play ready: nine or ten hours a week for ten weeks, but be careful with the scheduling: ‘It’s vital that children are not kept at rehearsals for any longer than necessary. They get bored and stop concentrating.’ As for crowd control backstage on dress-rehearsal day, ‘It’s impossible unless you have at least three dragon-ladies keeping order.’

Special effects or not? ‘Don’t think that by spending a fortune on technology you’re going to have a great show,’ advises Morell. Over-reliance on light effects is a pitfall: a play needs human energy and soul. But these days when most schools have ICT departments, it can be a good idea to be ambitious with your effects, especially if the play is Peter Pan. For a recent Sherborne Prep production of Peter Pan, the director Maria Trkulja (with the help of the ICT department) did ‘green-screen technology’ which involved Peter and Wendy lying on a piano stool in the flying position: this was digitally converted into impressive flying effects.

Should you let a schoolmaster or mistress loose on writing or directing the play? Beware the teacher who fancies himself as a playwright. I’ve heard of a dreadfully tedious play at a leading prep school, by a history master who had taken half his life to write it: it was about a minor local-historical event, and it went on for hours. There were more scene changes than words. It’s vital, a mother at the school said to me, that in such cases the parents are given a large glass of wine before the play to blur the experience. ‘Everyone thinks they can direct a play,’ said Damaris Lockwood. ‘I went to a prep-school play recently which was directed by the headmaster’s wife after the head of drama had been sacked.’ It was dire.

But don’t write off history masters as playwrights entirely. Among the prep schools of England you still find some self-effacing geniuses who change children’s lives by their brilliance. One such is Adrian Boote, inspiring history master at Hanford School for girls in Dorset, writer of spot-on school reports, and married to the headmistress of Bryanston. He writes the fabulous last-day-of-summer-term plays for Hanford, performed on the lawn beyond the hockey pitch, basing them on classics (Cinderella, Odysseus and the Pied Piper) but bringing in references to Miranda, Downton Abbey, William and Kate, and The Apprentice. Adrian Boote’s own ‘don’ts’ are as follows:

‘Remember that it’s not for you, it’s for the children and their parents. Let the pupils “own” it if they can. The more you can incorporate their ideas, the better. Don’t force the play to turn out the way you saw it in your head. It’s bound to take on a life of its own. Don’t have too much action: too much fighting, too much running, too much keeling over and dying. Focus on costume and dialogue, not on props and scenery. Keep it moving. Don’t expect all the pupils to love their part; but try not to let them swap too much, as with 40 or 50 one-line parts this could turn into a nightmare. Don’t expect every lovingly crafted line to hit the mark. All too often, the girls (over-keen for their moment) will speak their line while the laughter for the previous line is still going on, drowning out the sound. If you get a two-thirds strike rate, you’re doing well.’

Finally — and this is the case for all schools — don’t be bullied or swayed by competitivnes and discontentment about parts. I’ve heard of a competitive father (one who scored six sixes in a row in the fathers v. boys cricket match) who was furious because his son had a small part; of enmities between parents and boys caused by this; of children counting and comparing how many lines they’ve got in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The important thing is to show each child what he or she can do to make their own role, however small, the best it can be.

From the Spectator’s Independent Schools supplement September 2013

Comments