The cost of living crisis is confronting Westminster elites with the stark reality of some of the dubious policy choices they’ve recently made. Last week, the government was forced to postpone its ban on buy one get one free deals on ‘junk food’. The foolishness of outlawing cheap food – a policy Boris Johnson adopted after his spell in intensive care – has been laid bare now that inflation has risen to a 40-year high.

Soaring energy bills ought to give proponents of eco-austerity similar pause for thought. Dozens of retail energy companies have gone bust in recent months. We are shipping fracked gas from the US while banning the technology here. We have undermined investment in the North Sea and are deliberating on a windfall tax on energy companies – meaning a new wave of investment in the sector will never come if companies believe a tax raid lies just around the corner.

Perhaps fearful of changing public attitudes towards the climate emergency, Chris Skidmore – the Conservative MP who earlier this year set up a Net Zero Support Group – is now launching a ‘Rolling Thunder’ tour of the country to promote the benefits of cutting carbon. The former energy minister has insisted that we can be ‘early market leaders’ in renewable energy. Going green, he says, will leave Britain ‘warmer and richer,’ while allowing left-behind communities to be ‘reindustrialised’.

For years, the benefits of net zero have been exaggerated

Skidmore is right that green opportunities abound, but it might pay to learn from the past. Between 1990 and 1999, the UK’s energy policy was a striking success. Prices for domestic consumers fell by 26 per cent and the fall for industrial consumers was even greater. Energy-related greenhouse gas emissions per unit of GDP fell by 45 per cent between 1990 and 2010.

This was quite some achievement – and it happened because of privatisation and deregulation. The UK became a world leader in ending the domination of dirtier coal. The government didn’t pick winners, consumers and businesses did, and as a result they chose the best and cheapest technologies first. If we want Britain to be an energy leader again, we should liberalise energy markets, not invest prematurely in high cost, early prototypes that will raise prices for British consumers while bringing them down for the rest of the world once they have developed.

We now face an energy trilemma, with politicians unwilling to make the requisite trade-offs between security of supply, affordability and decarbonisation. The government is hiking costs with feel-good environmental charges while simultaneously implementing a price cap to keep prices low. As if that weren’t economically questionable enough, now the Net Zero Support Group is suggesting that responsibility for paying green levies be transferred from billpayers to oil and gas companies. But firms don’t pay taxes, people do. And many of the opportunities offered by green policies – the kind that Skidmore hopes will level up Britain and boost GDP – will come at the expense of other opportunities that are closed off.

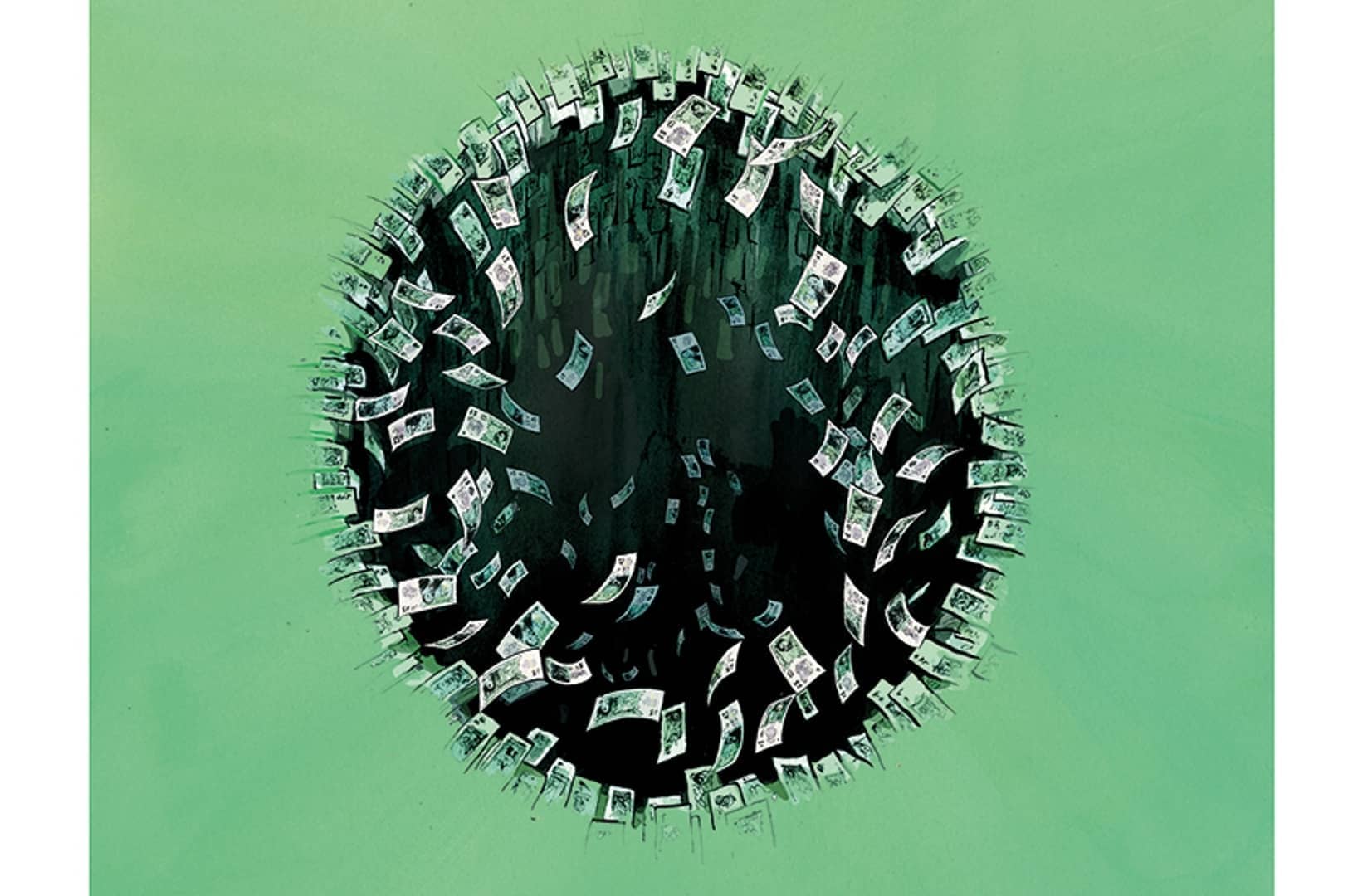

When the government asked Dieter Helm to look into what it was doing to meet the net zero target, the economist concluded that up to £100 billion had been wasted, largely from investment in technologies which hadn’t matured to the point where they were cheaper than the alternative. When the Climate Change Committee published a Net Zero Report in 2019, it was criticised for a lack of rigour and transparency – yet its conclusion that the 2050 target was ‘necessary, feasible and cost effective’ encouraged parliament to wave it through without even a Commons vote.

For years, the benefits of net zero have been exaggerated, while politicians have subscribed to the view that picking winners is superior to letting the public decide through their choices. As Stuart Kirk – the HSBC banker who was reportedly suspended for making ‘nut job’ climate remarks – pointed out, it is ‘heresy’ to question the climate change narrative.

Like Skidmore, Kirk believes that we need to get away from the doom-mongering. But in a presentation last week, the banker observed that ‘humans are spectacularly good at managing change’. Eco-fanatics, on the other hand, push the idea that state-imposed bans and targets and fixed dates are required for a low-cost, low-carbon transition. That’s not how innovation works. Instead, government should facilitate the market discovery process with a border-adjusted carbon tax. This wouldn’t require anyone to know or predict which particular technology will work best. And it wouldn’t cause a collapse in investment in gas generation at a time when our reserves are depleted.

Both fans and critics of net zero should welcome Skidmore’s promotion of new solutions to the climate challenge. But it should be accompanied by an honest discussion about the cost and where that burden will fall, at a time when the rise in food and energy bills is already swiftly outstripping the disposable income of thousands.

Comments